Have a drink with: The Thanksgiving Turkey

Our dinner, who art in oven…

Ask it about: Patriotism, Christology, stuffing.

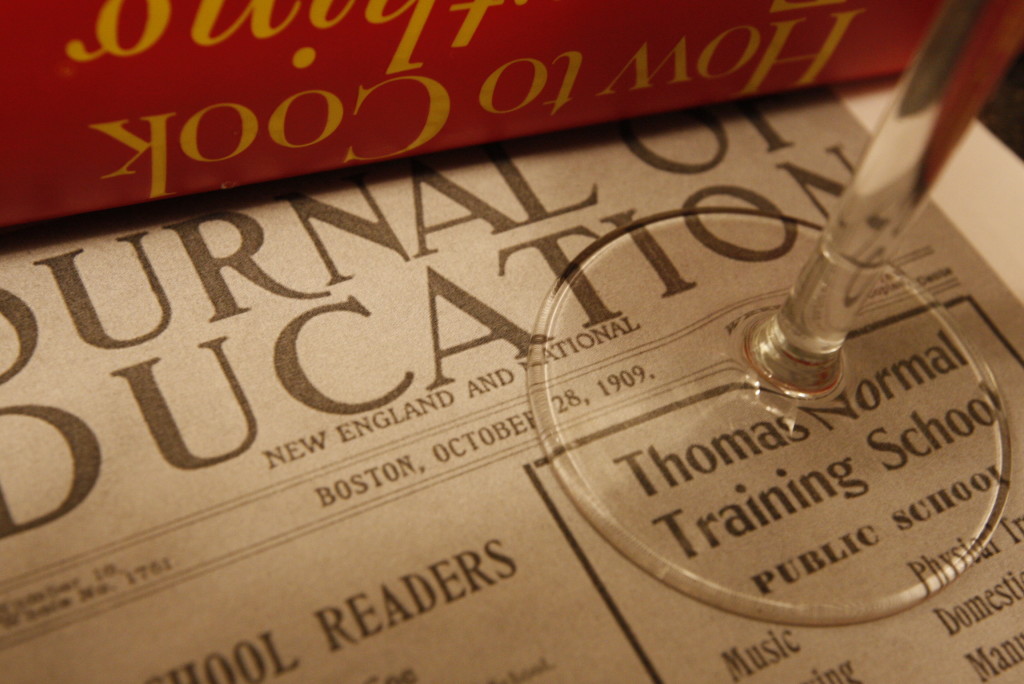

On October 28, 1909, the Boston-based Journal of Education – the nation’s oldest continuously published educational journal – prepared its readers for Thanksgiving by printing a suggested script for a holiday-themed school play.

This seems harmless enough – festive, even! – until you realize the whole exercise kicks off with a creepy read-aloud poem entitled “The Martyrdom of St. Turkey,” which no doubt traumatized any of the students so unlucky as to be assigned to read it.

Let’s begin.

“[A big drawing of a turkey on the blackboard.]”

Okay, well, that’s nice.

“First pupil –

How St. Turkey came to sainthood,

And at last was canonized,

Is the burden of the story I shall tell;

How they grew him –

How they slew him,

And his corpse anatomized,

Till we bless him now with candle, book and bell.”

Wait. There’s going to be anatomizing? I thought we were just going to eat green bean casserole and have awkward conversations about Donald Trump.

“Second pupil –

Martyr was he to their kindness,

For they loved him to the death,

As other saints besides have breathed and bled;

Since they fed him

To behead him,

And to take away his breath.

As they stuffed him, living, so they stuffed him, dead.”

Adorable rhymed couplets! Ritual slaughter! Stuffing! So, who wants gravy?

“Third pupil –

No more struts he in fine feather –

No strong pinions now has he

To upbear him even to a final rest;

But they roast him,

And they toast him,

While they bring him out to be

This, our grateful nation’s proud and honored guest.”

I’m really not comfortable making tomorrow’s soup with the bones of a Jesus allegory.

“Fourth pupil –

Comes he steaming to the table,

Like a life on altar laid,

Veiled in incense as they bear him from the fire;

Where they greet him,

And they eat him,

While his praise is sung and said,

And the festive spirit rises higher and higher.”

Is this like some weird Castle Black funeral at this point? Oh, God, is the turkey a White Walker now? Where’s everybody going? Hello? There’s still pie!

“Fifth pupil –

Blessed martyr of Thanksgiving!

May we hold thy memory dear

Long as Time shall roll its breakers at our feet!

Having crowned thee,

We’ll surround thee,

Sovereign of each passing year,

As before thy happy shrine and board we meet.”

We’ll all be dead soon, so pass the dark meat. And a Scotch, will you? Dig in, kids!

“[N.B. Little souvenir cards with a turkey in silhouette may be made and exchanged by the pupils, each writing a Thanksgiving quotation on another’s card.]”

You can bring these souvenir cards to therapy when you’re thirty and have to explain why you are both paranoid and vegan.

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone. I’m gonna go watch Adam Sandler now.

Fun facts:

The poem is followed by an essay on the wild turkey, which begins: “There is no reason why the Pilgrim fathers of old should not have enjoyed turkey dinners at Thanksgiving just the same as we do now. There were wild turkeys in plenty then. They were found in the forests all over our country. The turkey greeted the exploring Spaniards.”

Not entirely wrong: William Sitwell’s masterful, luxurious book A History of Food in 100 Recipes talks about the turkey’s early and enduring popularity in Latin America and the larger West, drawing upon an Aztec recipe for turkey tamales related by Bernardino de Sahagun, a 16th century Franciscan missionary. (Leftovers!!)

Benjamin Franklin only sort of advocated for the humble turkey as the national bird, essentially complaining of the original artwork for the national seal: “Well, it looks more like a turkey than an eagle, and it isn’t like that’s the worst thing ever.”

The traditional Thanksgiving narrative is by now pretty well known to be a slapdash, racist creation myth, thanks to the attention of writers like James Loewen, whose fantastic book Lies My Teacher Told Me dives into the grittier aspects of the “settlement” of the United States as we today know it. That said, my personal favorite rendering is by Wednesday Addams.

Despite the ambiguous roots of the “traditional” Thanksgiving holiday, its transformation into the modern exercise of gratitude, homecoming and community is socially interesting and uniquely American. In the 19th century, there was an overall push towards holidays at home, in an effort to avoid general public drunken mayhem. Combine a handful of Puritan hangers-on (the idea of a day of thanksgiving; Thursday holidays to keep Sunday free for church) with a consolidation of traditional English fall feasts into one convenient day, and you get a bunch of New Englanders very happy to stuff themselves silly at home.

And stuff they did; an article in Gastronomica* notes: “The writer Harriet Beecher Stowe remembered her childhood thanksgiving celebrations in Litchfield, Connecticut: the meal took a week to prepare, and it was planned so that everyone could attend church service in the morning. The elaborate dinner inclued turkey, chicken pies, plum puddings, and four types of pie for dessert.”

19th century writer and editor Sarah Josepha Hale (writer of “Mary Had A Little Lamb”) had the idea that an official Thanksgiving holiday could pull the nation together in its antebellum discord, going so far as to suggest that churches take up Thanksgiving Day collections to purchase, educate and repatriate slaves. Writing to Lincoln’s secretary of State William Seward, she urged the President to declare a national holiday – which he did in 1863. (The Pilgrims’ story was tacked on well later on.)

Additional Reading:

The Turkey, The Journal of Education, October 28, 1909

A History of Food in 100 Recipes, William Sitwell

Lies My Teacher Told Me, James Loewen