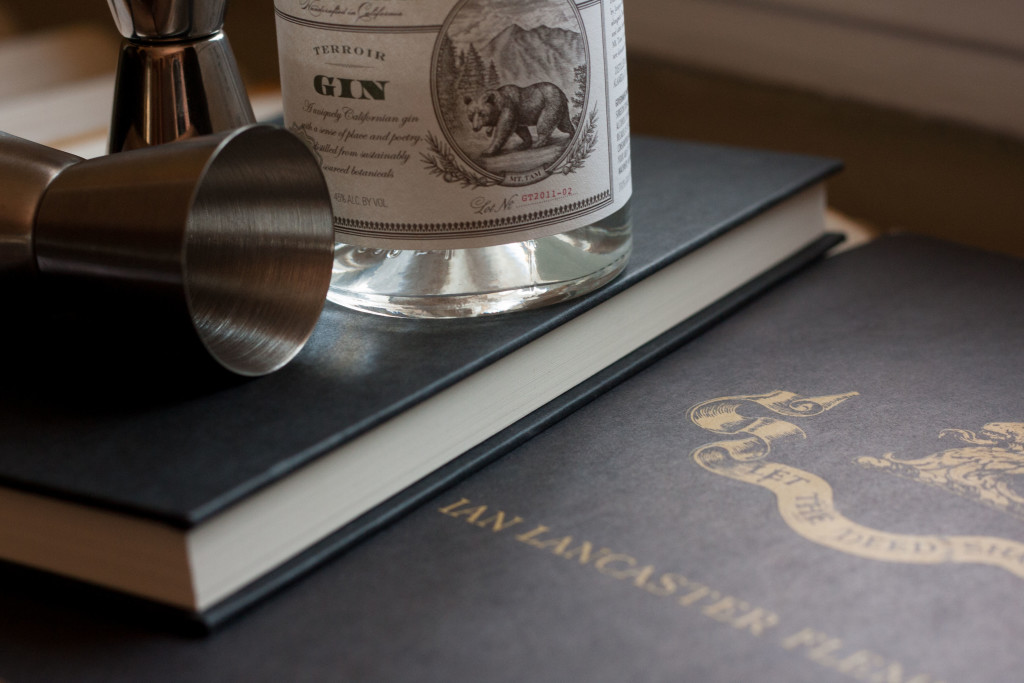

Have a drink with: Ian Fleming

Shaken, not stirred.

Ask him: hey, can we bring drinks into the library?

In 1963 a major exhibition of rare books and printed treasures called Printing and the Mind of Man went up at the Eleventh International Printing Machinery and Allied Trades Exhibition (IPEX) in London, displaying some four hundred historic books borrowed from dozens of libraries and private individuals and billing itself as “the most impressive collection of books ever gathered under one roof.” Among other treasures, visitors could see a broadsheet copy of the Declaration of Independence and a one-of-a-kind leaf from the Gutenberg Bible. The King’s College library at Cambridge was the leading exhibitor, with fifty-one items.

In second place, with forty-four: Ian Fleming.

Ian Fleming is known to history as the writer who gave the world James Bond, but spy novels weren’t his only stock in trade.

The writer did not speak often about his passion for rare books (though he did own The Book Collector, a British journal), but it was clearly an important pursuit. The London exhibition showed but 44 books out of more than a thousand he owned. Instead of collecting showpieces for their own sake, Fleming preferred books that had been responsible for the world’s 19th century lurch into technology, science and industry, books “that made things happen.”*

Fleming’s cataloguer notes that the author’s collection was an attempt to gather first editions that demonstrated “the original contributions of the scientists and practical workers, the total body of whose work has been responsible for the modern revolution.”**

Thing was, Fleming was a man of action and grand ideas as much as they often seemed to elude him personally – he’d been mediocre as a student, a failure as a stockbroker, prickly with women, a bureaucrat in the war, a journalist for much of his pre-Bond writing life. He wanted to be part of the action and indeed had the temperment and the drive for it, but ended up fundamentally a cranky observer, living out his most idealized adventures in writing.

This unifying theme – essentially, a masculine literary Swiss Army knife for the modern era – made for a fascinating collection: Fleming owned first-edition Rousseau on the social contract; Einstein’s relativity work, the prospectus for construction of the Suez Canal. He kept Freud and Nietzche as well as the discovery accounts written by Darwin, Marie Curie and Alexander Graham Bell. Nor were more physical matters forgotten, as he owned Baden-Powell on the Boy Scouts, Alfred Nobel’s study of dynamite, and Walter Camp’s New Way to Keep Fit. Each book had a custom fleece-lined storage box, color-coded by topic.

There were books on time, electron theory, economics, metallurgy, meteorology, urban planning, criminology, billiards and even The Foundation of Modern Sanitation.

Everything a spy needs to know.

Fun Facts:

I always loved the bit in Casino Royale where “the men were drinking inexhaustible quarter-bottles of Champagne, the women dry Martinis.” (Girly drinks, what?)

Fleming came up clumsily through a pedigreed upbringing – he attended Eton (far better at sports than academics), fumbled at Sandhurst, and after a brief stint at the Reuters news agency he spent some time in London finance, calling himself the world’s worst stockbroker. In World War II he became assistant to the director of British naval intelligence, notably advocating for the use of small advance commando units to capture enemy documents or ciphers before they could be destroyed. Fundamentally it was a desk job, but the experience no doubt laid the foundations for the creation of the Bond universe.

A note in Fleming’s own handwriting appears in the Lilly exhibit catalog: “I have always smoked and drunk and loved too much. In fact I have lived not too long but too much. One day the Iron Crab will get me. Then I shall have died of living too much.” The “Iron Crab” was Fleming’s euphemism for heart disease, which did in fact get him in the end; and this lament appears, revised, in From Russia With Love.

Somewhat opaque and unpleasant in person, Fleming was blunt, moody, gruff, and reliably had a buzz on. A friend once remarked that someone pretty much had to die to get grief out of Fleming; and though he was rarely without female company, he largely and restlessly viewed women as inferior amusements, “like pets, like dogs.”* Bond reflected this acid detachment.

The cinematic Bond isn’t without real-world intrigue, either. In 2013, the estate of screenwriter Kevin McClory and film producers settled a fifty-year legal fight over Bond rights – thanks to which the newest Bond film features SPECTRE and its head Ernst Stavro Blofeld.

McClory helped Fleming write the screenplay for what became Thunderball, and spent decades afterwards in vicious litigation over related rights, claiming Fleming hadn’t credited him and trying to create a parallel series of Bond films (see: Never Say Never Again, released with Sean Connery only months after the premiere of the Roger Moore Octopussy). There are a number of great articles on the dispute (Atlantic, Hollywood Reporter, Chicago Lawyer) and I totally encourage my legal friends to geek out on James Bond and the Laches Defense (Danjaq LLC, MGM et al v. Sony Corporation (9th Cir. August 27, 2001)).

Remember Chitty Chitty Bang Bang? Fleming wrote the book for his son.

Additional reading:

*Ian Fleming, Andrew Lycett

Ian Fleming’s Commandos, Nicholas Rankin

**The Ian Fleming Collection of 19th-20th Century Source Material Concerning Western Civilization together with the Originals of the James Bond-007 Tales (exhibition catalog)

Ian Fleming Collections @ Indiana’s Lilly Library