Have a drink with: The All Writs Act

Ain’t no party like a statutory party, because a statutory party

is subject to judicial review.

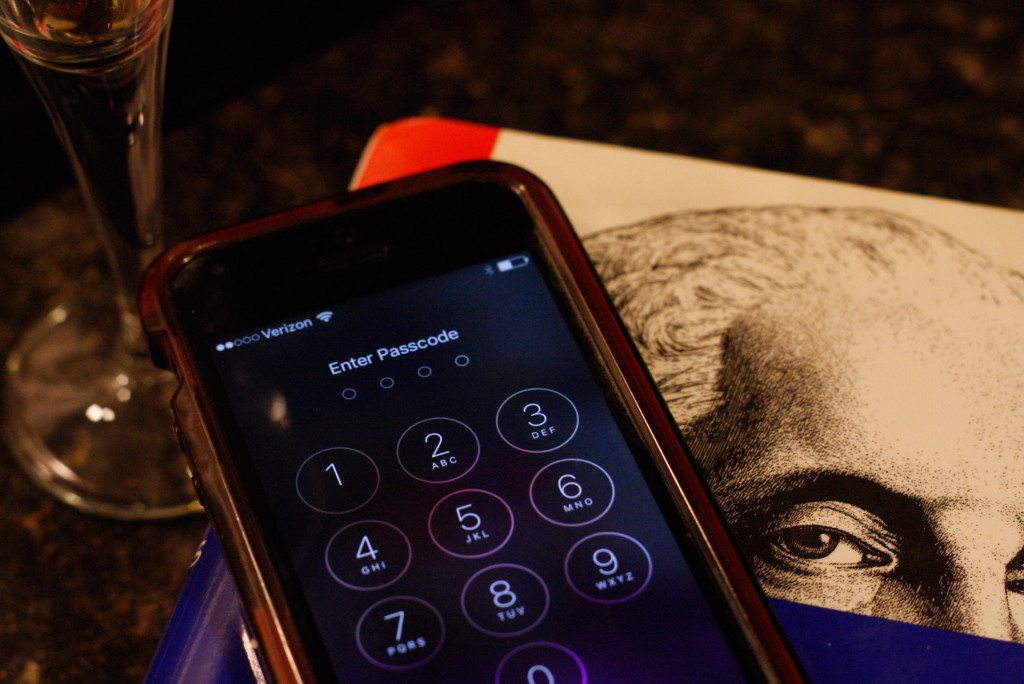

Don’t give it: your iPhone passcode

Beginning with the iOS8 version of its operating system, Apple has used encryption that makes it impossible for anyone but the user to access the passcode-protected information on their iPhone. Yesterday, a California district court issued an order asking Apple to create a bypass by which the FBI could access information on a recovered iPhone linked to the December shootings in San Bernardino, citing the All Writs Act – a piece of legislation derived from the Judiciary Act of 1789 – as legal basis.

In an open letter Apple has opposed the order, citing the integrity of its customer relationships and the sanctity of customer information.

This is fascinating, and on the bleeding edge of technology, privacy, law and communication as they intersect in the 21st century. But in the meantime, wait: did that say 1789? Are we really going after an iPhone with a muzzle-loader?

Yes, really. And this isn’t some musty old statute being dragged out on a technicality, either.

The Judiciary Act was written when the Constitution was barely two years old and George Washington had only been President a few months. Begun only a day after the U.S. Senate first reached quorum, it predates the Bill of Rights (not ratified until 1791), and has been argued by folks like former Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O’Connor to be a “crucial foundational part” of the American tradition. The Act establishes the independent American judiciary: specifying the nature and structure of the Supreme Court, setting up district courts and the requirements by which early justices “rode circuit” to serve and familiarize themselves with different communities, and talking about everything from the limited scope of federal jurisdiction to the U.S. Marshals.

On September 24, 1789, George Washington signed the Judiciary Act, Section 14 of which reads:

“And be it further enacted, That all the before-mentioned courts of the United States, shall have power to issue writs of scire facias, habeas corpus, and all other writs not specially provided for by statute, which may be necessary for the exercise of their respective jurisdictions, and agreeable to the principles and usages of law.”

After a few centuries and some polishing, it survives as the All Writs Act, which reads:

“The Supreme Court and all courts established by Act of Congress may issue all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and agreeable to the usages and principles of law.”

At its simplest, the All Writs Act applies when there isn’t law to provide direction between a given point A and B (and really no alternative on the books, not just a decision that the existing statute is just too much of a bummer), and allows courts to come up with a “reasonable and necessary” gap-filler.

Remember that the U.S. legal system borrows from England’s common law tradition (in contrast to most of continental Europe, which plays for Team Civil Law). The concept of a writ was in use as far back as Norman England, and while it’s had some plural meaning over time – referring to all manner of legal documentation – under the common law system the word essentially means “court order.” The king wants something done? He issues a writ.

Historically, the King’s Chancery managed the King’s justice – so the Chancellor’s power to issue writs and manage legal process is fundamental to the modern doctrine of equity, which is exactly where the All Writs Act plonks us: the idea that a court can use its discretion to achieve justice where existing statutory authority doesn’t provide.

I’m guessing the Chancellor had no clue how to unlock an iPhone, though.

Fun Facts:

The 1789 Judiciary Act was litigated in perhaps the most famous case ever, Marbury v. Madison. In 1803 the Supreme Court decided to look at just how big its own britches were, and by its decision in Marbury set up judicial review of Congressional legislation – the idea that the Supreme Court can declare laws unconstitutional (which it did with part of the 1789 Act). Essentially: the Constitution is either a superior law or it’s on the level with ordinary legislative acts and at the mercy of the legislature to change. If the first part is true: a law “repugnant to the Constitution” is no law at all. If the second: constitutions are stupid. We went with the first bit.

Also amusingly relevant, Marbury v. Madison deals with what happens when late-term Presidential judicial appointments get weird. President John Adams nominated some judges in D.C. at the close of his administration. President Jefferson, incoming, said that if a commission hadn’t been delivered before the end of Adams’ term he wouldn’t recognize it. Lawsuit follows.

Home state shout-out: the principal author of the Judiciary Act was Senator Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut, who down the road would serve as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

A few scholars have noted Allied Chem. Corp. v. Daiflon, Inc., 449 U.S. 33, 36 (1980) when discussing the sparse history and use of the All Writs Act, notably the case’s reference to Gilbert and Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore: “What never? Well, hardly ever!”

Additional Reading:

The original text of the Judiciary Act of 1789 and its current version in the U.S. Code (28 U.S.C. §1651(a)).

Watch Sandra Day O’Connor rock it out live on The Judiciary Act of 1789 and the American Judicial Tradition: the full Monty or a sharp two-minute excerpt, courtesy C-SPAN.

Fantastic blog post from the National Archives with images of the original 1789 Act as well as Washington’s initial nomination list of judges, attorneys and U.S. Marshals.

Check Popular Mechanics’ summary of the Apple dispute and the All Writs Act, including a video on surveillance.

The always-excellent Electronic Frontier Foundation on the long-simmering background of the Apple dispute, in 2014 and 2015.