Have a drink with: Fanny Hill

Grin grin, wink wink, say no more?

Ask her about: Sex and the (eighteenth-century) city

My friend Dan Klau, who writes a wonderful appellate law blog at Appealingly Brief, and who also just launched a government-accountability site at CT Good Governance – because transparency is very cool – recently posted this link about Ted Cruz’s advocacy as solicitor general in support of a Texas state law outlawing the sale or promotion of sex toys.

In 2007, Cruz and his team prepared a 76-page brief to the 5th Circuit, arguing to uphold the Texas statute and claiming in part that “‘any alleged right associated with obscene devices’ is not ‘deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and traditions.’”

I’ve got news for Ted: few things are a more consistent and popular part of the Nation’s history and traditions than alleging rights in the obscene.

Don’t believe me? Just ask the U.S. Supreme Court about Fanny Hill.

In the early 1700’s, young Englishman John Cleland lived in Mumbai as an employee of the East India Company, and legend says that on a dare from a friend, he set out to write an erotic novel without using any dirty words. The resulting explosion of euphemism and (wink-wink, nudge-nudge) storytelling was the decidedly NSFW Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure. An unblinking catalog of sexual adventures, the story of a teenaged prostitute was printed some years later in 1748 while Cleland sat in London debtor’s prison, and it got him and his publisher arrested on obscenity charges nearly immediately.

It also sold like hotcakes. And yes, I hear you say: but that was EUROPE. We in America had deeply rooted history and traditions! And Puritans!

Uh-huh. The Puritans swore that “use of the Marriage Bed” was “founded in mans Nature,”* and did I mention Ben Franklin owned a copy of Fanny Hill?

Small niche press, underground copies and the first American obscenity trial (1821) kept Fanny Hill quietly thriving until the 1960’s, at which point G.P. Putnam and Sons – no doubt encouraged by Penguin Books’ acquittal over Lady Chatterley’s Lover – decided to print it commercially, and it started thriving publicly. Court records mention that “an unusually large number of orders were placed by universities and libraries; the Library of Congress requested the right to translate the book into Braille.”**

Then some kid brought it home to read, his mom freaked out and called the state of Massachusetts, lawsuits followed, and before you know it the U.S. Supreme Court is reading 18th century pornography. (It’s for work, dear.)

Massachusetts courts had decided that, because Fanny Hill violated its own state obscenity laws, the novel was not entitled to First Amendment protection (obscenity being excluded from free-speech rights). The U.S. Supreme Court reversed judgment, claiming: even assuming a book is obscene within the meaning of the Massachusetts state law, as long as nothing illegal is going on, and there’s even a little social value attached to the work, censorship on First Amendment grounds won’t stand.

There was no majority opinion in the case, but in the wide range of commentary the judges do manage to be entertaining in unexpected ways. The voices arguing most stridently that the stuff is smut are the ones most eager to list lurid stories from the text, and Justice William O. Douglas’ refreshingly libertarian opinion even includes the unfazed viewpoint of a Universalist minister on the book:

“Long ago Plato said, ‘What is honored in a country will be cultivated there.’ More and more, we reward people for thinking alike and as a result, we become frightened, beyond belief, of those who take exception to the current consensus. If our society collapses, it will not be because people read a book such as Fanny Hill. It will fall, because we will have refused to understand it.”**

Right, Ted?

Fun Facts:

The Good Old Days: yes, there were brothels in early America. And a LOT of bars (in 18th century Philadelphia, roughly one per 130 residents). And cannibalism!

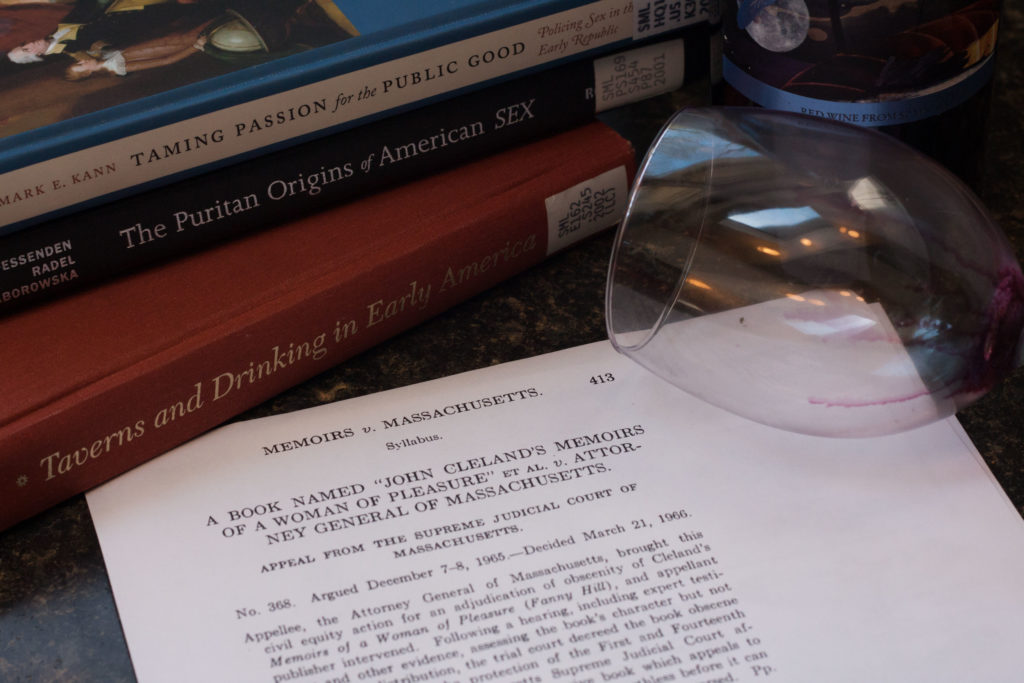

The full Supreme Court heading, in all its glory, is: “A Book Named ‘John Cleland’s Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure’ v. Attorney General of Massachusetts.”

Some scholars have argued early American efforts to police citizens’ private lives were due in part to the fact that all this revolution stuff and “individual rights” talk got young people frisky, and “they were angry that their great experiment in liberty had seemingly given license to young people and others to act as if illicit sexual behavior, like free speech, was their natural right.”^

There was at the time a robust continental and global tradition of explicit literature and art. Christie’s once auctioned an antique dildo in a box. And in London you could get a weird Zagat-style guide to local hookers.

Justice Potter Stewart got all the good obscenity cases. His was the famous line about pornography in Jacobellis v. Ohio: “I know it when I see it.”

John Cleese, on mollusks: “…makes Fanny Hill look like a dead Pope.”

Additional Reading:

John Cleland, Memoirs of Fanny Hill

* Edmund S. Morgan, “The Puritans and Sex,” New England Quarterly 25 (Dec 1942)

** Memoirs v. Massachusetts, 383 U.S. 413 (1966)

Totally recommend this great Boston Globe article on the anniversary of the Memoirs v. Massachusetts verdict.

^ Mark E. Kann, Taming Passion for the Public Good: Policing Sex in the Early Republic (2013).