Have a drink with: Anna Jarvis

Don’t even get her started on “Candy Day.”

Ask her about: Her mother.

Anna Jarvis was a public school teacher and devout Methodist, and widely regarded as one of the inventors of the Mother’s Day holiday. She would not seem to be the type of person who would try to flip off a room of candy manufacturers, but history is full of surprises.

Anna left small-town West Virginia in her twenties, settling near her brother in Philadelphia. Jarvis, who never married, simultaneously adored her mother and found her frustrating: she admired her mother’s resolve and hard work as a community organizer, but disliked her assent to the sort of small-town values that limited daughters’ options (ahem). She glorified her mother’s skill and virtue, but may well have been worn out by the imposed assumption that she would be her mother’s full-time caregiver through later-life illness. Regardless of the emotional stew involved, when Mrs. Jarvis died in 1905, her daughter was devastated.

In an effort to honor her mother’s piety, hard work, sacrifice and strength in the face of grief (Anna was one of only four siblings to survive their childhood), Anna first sought to have a local memorial placed at the church her mother had loved and served in Grafton, West Virginia.

According to author Eric Leigh Schmidt, it was not simply admiration for her mother’s toil that drove Anna Jarvis to push for more lasting recognition: “It saddened her that her mother’s hopes to have a college education had been thwarted by ‘home responsibilities’ and that her mother’s ‘own pleasure and ambitions’ had been ‘restrained by the ties of motherhood.’” Anna Jarvis was well aware that she could reject that restraint, and acquire a public role that had escaped her own mother.

What started as a private intention to honor her mother soon expanded, and by 1907 she had grown towards the idea of a day that would remind all people to pause and write their moms a friggin’ letter for once. Not to mention, she felt, the calendar was a little bro-heavy as it was: “New Year’s Day is for ‘Old Father Time,”‘ she wrote, and “Washington’s Birthday is for ‘The Father of his Country….Memorial Day is for Departed Fathers. Independence Day is for Patriot Fathers…. Thanksgiving Day is for Pilgrim Father.” What about the mothers, indeed?

A campaign based on shoe leather, social networking and letter-writing led Mother’s Day into wider acceptance, ultimately leading to Woodrow Wilson’s designation of a formal national holiday in 1914.

Anna was pleased that this tribute to her mother had taken root. She was far less pleased that commercial interests co-opted the holiday nearly immediately. Commercial florists zeroed in on the white carnation that Jarvis had worn for various celebrations (her mother’s favorite flower), and through the early 20th century, some of the biggest advocates for Mother’s Day celebrations were people eager to profit from it: advertisers, greeting card manufacturers, florists.

Anna hated the quick commercialization of what she had intended as a solemn and heartfelt pause to honor mothers, and she did not take it sitting down. In 1923, Philadelphia papers noted that she walked straight into a candy-manufacturers’ convention to give the crowd a piece of her mind, accusing Big Candy of having “profiteered” and “gouged the public” through Mother’s Day marketing – to say nothing of rumors that they hoped to create a “Sweethearts’ Day” to boost sales. Coverage noted that Miss Jarvis was escorted from the convention by a house detective, though she claimed to have left of her own free will.

Call your mom this weekend. Anna would approve.

Fun Facts:

Ann Reeves Jarvis (Anna’s mom) was a powerhouse in antebellum and Civil War West Virginia, and in an effort to improve difficult life in Appalachia, she advocated for social union, religious virtue and public health: her women’s work groups were especially focused on improving hygiene and public health, especially for mothers. She was active in the Methodist church during a difficult period of conflict, and offered care and charity to soldiers in need in both the Union and Confederate armies.

Mother’s Day celebrations in the U.S. have a variety of roots – in addition to Anna Jarvis’ structural efforts, the idea of honoring mothers also draws upon a nineteenth century Civil War culture of women’s groups, and the efforts of women like Julia Ward Howe, who in 1870 hoped to use mothers and the idea of a mother’s holiday to bring women together as peace advocates (read her proclamation here).

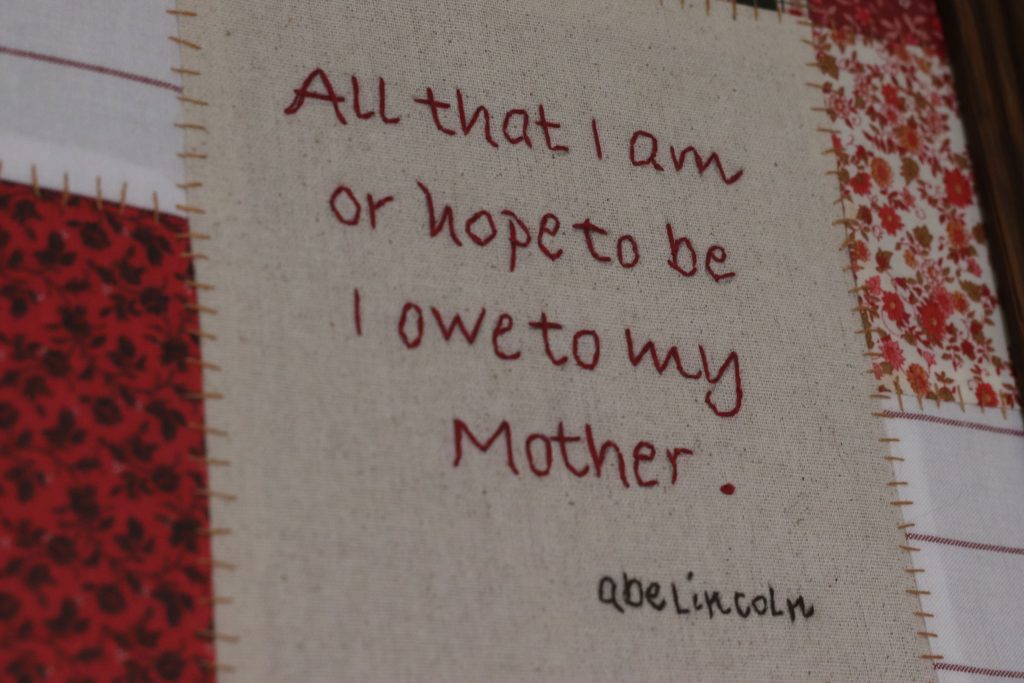

Looking for some good historical Mother’s Day words to share? You could borrow from Abraham Lincoln, who said (likely of his stepmother): “All that I am, or hope to be, I owe to my angel mother.”

Additional Reading:

“Mother’s Day Founder Ejected From Meeting,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 18, 1923

“Charges Candy Men Profiteered,” The Pottsville Republican, May 17, 1923

Leigh Eric Schmidt, “The Commercialization of the Calendar: American Holidays and the Culture of Consumption, 1870-1930,” The Journal of American History, Vol. 78, No. 3 (Dec., 1991)