Have a drink with: Claire Heliot

“Sentimentalist and lion tamer.”

Ask her about: herding cats

In 1905, the New York Hippodrome opened its doors with a banner performance of A Yankee Circus on Mars, a freewheeling half-circus, half-opera in which the King of Mars, acting as an intergalactic talent scout of sorts, comes to Earth to save a failing New England circus. A splendid spectacle, the show featured an ensemble of hundreds of actors wearing grand robes and frolicking amidst fifty-foot dragon sculptures, live elephants and decadent garden sets. Its star was a lion tamer named Claire Heliot, making her major American debut.

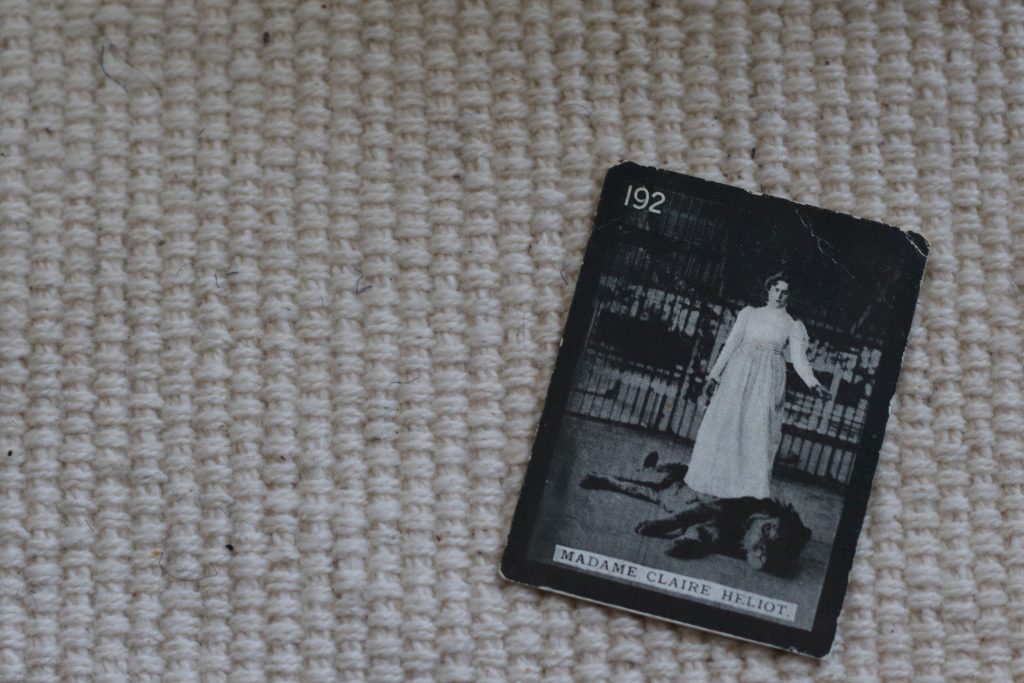

A Yankee Circus on Mars had snapped up Heliot for good reason: she was a sensation in the turn-of-the-century press, journalists marveling over this fair-haired young woman who, alone in the ring in a white satin gown, commanded the attention of a dozen lions. In her showpiece act, Heliot set an elegant table and invited the lions to sit with her, feeding each in turn a hunk of horseflesh with her own fingers, and as a closing flourish offering them “her own pretty head as a delectable morsel for dessert.” (The dinner guests respectfully declined this course.) Heliot’s lions agreeably performed with a group of boar hounds, doing tricks and pulling the dogs about in a chariot; and then in an act that seemed to defy both nature and physics, the lions Sascha and Nero walked from opposite sides of a tightrope towards each other, pausing to balance nose-to-nose in the center.

Heliot would lie down across the bodies of four reclining lions, pose for portraits in her boudoir cuddling the mane of a massive male, and play with the lions as though they were happy kittens. She typically finished her act by slinging a 350-pound male over her shoulders like an overgrown scarf and triumphantly striding from the ring.

Press headlines described Heliot as “frail but fearless.” She was neither; but they did not know what else to say.

For a woman to step in the ring with a wild animal in the early 20th century threw any number of social norms out the window, even in a flexible realm like the circus ring: here was a (frequently unmarried) woman, demanding and commanding attention, in a public sphere, openly engaging in dangerous activities. A male trainer of exotic animals was generally viewed as an intrepid performer with skilled dominion over toothy beasts; a woman in that capacity was, frankly, confusing.

Her proclaimed virtue, therefore, was neither strength, skill nor courage, but unfailing fidelity to existing power structures. A New York Times profile in the fall of 1905, when she was in town to perform in the Yankee Circus, announced that Heliot’s success came precisely from her lack of skill: “Being intrinsically, not artificially, feminine, she could not control the beasts by brute force. She governs them as the best of women govern the human brute, by trusting them blindly.” The Times reporter concluded that Heliot’s performance represented no less than “a solving of the mysteries of the Garden of Eden, where Eve was the first amateur lion tamer.”

Heliot was constantly promoted with reference to her nurturing qualities – she was described as a paragon of delicate womanhood, bathing her lions meticulously, flirting with them, caressing them and all but calling swallows to chirp over her head, Cinderella-style. One article emphasized, foreshadowing the thesis of Amy Sutherland’s 2008 “man as Shamu” marriage training manual, that it’s harder to train a husband than a lion. (Amirite, ladies?)

Not to mention that the act itself was a ritualized performance of the feminine: rather than bluster or crack the whip around her lions, for Pete’s sake, Claire Heliot threw them a dinner party.

One reporter after another went through a litany of how’d-she-do-it questions, believing the game had to be rigged: were the lions drugged? Tame? Had they been declawed, or their fangs blunted? No: chloroform would make a lion nothing more than a very untheatrical lump on the sawdust floor; wild animals never fully lose their instincts; removing teeth and claws would doom the animal to deadly infection and would be cruel besides.

Much of the press coverage around Heliot’s performances disguised only thinly, if at all, the real reason that everyone watched so intently: the idea that her time in the spotlight was not only unnatural but fragile, and if – when? – she slipped up, femininity would not be enough to save her from wild instinct. Which of her “pets,” in the end, might decide to make a meal of her?

Heliot was far from being, as one publication suggested, the sort of petite lady who would be better off carrying a tiny dog with pink ribbons tied to its collar. She was far from sentimental, referring to her charges as “vaire oog-lee, sometimes;” gamely showed her many scars to reporters; and did not hesitate to flash a famously stern and commanding stare. She trained her lions not with the magic of guileless womanhood, but years of consistent, hard work conducted in multiple languages (born in Germany, Heliot spoke German, English and French, and preferred the latter with her charges).

Moreover, she did not expect her lions to be anything other than nature had made them. Relying on consistency and discipline, with clear eyes she admitted to one writer that a whip and a metal rod would do nothing if the lions ever truly meant to do her harm, and that even the giant boar hounds, alleged in some accounts to serve as eager enforcers, were afraid of the cats.

In the ring, Heliot was neither frail nor fearless. Offstage, Claire Heliot’s concerns were more immediate and sadly familiar in the #MeToo era: lions were trainable, but not men. “Somebody told her before she left Europe that New York was a very wicked place,” wrote her New York Times profiler, “and she is more afraid of burglars and bad men than she is of her lions. She sleeps with the lights burning all night in her apartments.”

Fun Facts:

The plot of A Yankee Circus on Mars was a cracker. In the show, a Vermont circus opens for the season and all is not well: the show’s in the red, the sideshow performers are rustling for their unpaid salaries and the local sheriff has arrived to auction off the show for whatever meat’s left on its bones. Before the sheriff can bring down his ax, a ship arrives with a delegation from King Borealis of Mars, sent to bring back some entertainment for the red planet, which ostensibly loves freewheeling entertainment more than dour Earth. The Martian delegation pays the circus’ bills (how that currency exchange works, Lord knows) and whisks the performers away to Mars where folks have not forgotten how to have a good time, and where King Borealis falls in love with a circus performer. After intermission, viewers were treated to a Civil War play, during which cavalry rode live horses into a giant onstage pool in a re-enactment of the Battle of Andersonville.

The New York Hippodrome was located in midtown Manhattan, between 43rd and 44th Streets on Avenue of the Americas. The venue seated more than 5,000 and had a stage large enough for 1,000 performers. The building – and advertisements for the Yankee Circus – are visible in this 1905 film clip.

One of Heliot’s lions, named Ralph, was mentioned in The Washington Post of January 25, 1906, as a veterinary patient: to prevent the lion “from going mad,” the Hippdrome’s vet, Dr. Martin Potter, dosed the lion with cocaine and restrained him with a rope net before performing surgery to remove a tumor from Ralph’s frontal bone. The tumor, according to the press, was occasioned by “the terrific attacks which the beast has made nightly against the bars of his cage in an effort to gain his freedom.”

Heliot was born in Germany and spent her early performance years there, with an early performance in 1897 in Leipzig; then expanded to tour Europe. By 1901 she was in England with 10 lions, and the United States in the early 1900s for circus performances including the Yankee Circus on Mars. She suffered a bite injury in 1907 that compelled her to retire from performing with lions, and for a time she bred horses and lived on a farm near Stuttgart. Heliot was financially ruined by 1920s hyperinflation, and her apartment was bombed in World War II in 1944. She died in 1953 and is buried in Stuttgart.

Additional Reading:

“Claire Heliot — Most Daring of Lion Tamers,” New York Times, October 29, 1905

Ellen Velvin, “Critical Moments With Wild Animals,” McClure’s Magazine (1910-1911)

Peta Tait, Fighting nature: Travelling menageries, animal acts and war shows (2016)