Have a drink with: Mark Twain & Henry David Thoreau

Bring water, though.

Ask them about: grilling tips

One of the current West Coast wildfires made news recently when investigation revealed it had been started by smoke bombs at a California gender reveal party. The accident (not the first of its kind, following a similar fire in 2017) has drawn harsh criticism, including from the blogger who invented the party trend – but this is not the first time fame-seekers have tried to duck responsibility for errant wildfire.

Before he settled on Walden Pond to contemplate a simple woodland existence (albeit with female relatives conveniently handling laundry service), Henry David Thoreau nearly obliterated the town of Concord, Massachusetts by making chowder. After an April day spent on the Concord River in 1844, Thoreau and his companion sat to cook fish for dinner – and as it was a windy day, and there had not been much spring rain, their cooking fire set nearby grasses alight. The resulting blaze ended up destroying three hundred acres of forest, and threatening the nearby town in the process. This seemed not to bother Thoreau, who wrote in his journal: “I have set fire to the forest, but I have done no wrong therein, and now it is as if the lightning had done it. These flames are but consuming their natural food.” The residents of Concord were of a different mind, muttering “woods burner” under their breath at Thoreau for years after.

Mark Twain set a large swath of Lake Tahoe forest aflame in 1861, an incident he describes in the travelogue Roughing It. Making a meal of bread, bacon and coffee while camping in the area with an acquaintance (intending to stake a timber claim), Twain lit a fire and went back to their boat to retrieve a frying pan. Hearing a sudden shout from his partner, Twain turned around to find that his campfire had jumped its bounds and was hungrily racing across the dry brush, a sight he regarded more like a spectator sport than a threat: “It was wonderful to see with what fierce speed the tall sheet of flame traveled! My coffee-pot was gone, and everything with it. In a minute and a half the fire seized upon a dense growth of dry manzanita chapparal six or eight feet high, and then the roaring and popping and crackling was something terrific. We were driven to the boat by the intense heat, and there we remained, spell-bound.”

Sometimes, the idiocy is in the interpretation rather than the ignition. In October 1871, fires raged across the Midwest, burning more than a million acres of land and killing some two thousand people (the Great Chicago Fire and an even more devastating blaze in Peshtigo, Wisconsin, occurred on the very same day). Scientists generally agree that the fires occurred due to a combination of weather conditions and land use decisions – then, as now, foresters cite climate, development and proper forest maintenance as key factors in fire severity – but in response, Ignatius Donnelly suggested a different cause: an apocalyptic comet.

Donnelly, a Minnesota Congressman and theorist regarding the Lost City of Atlantis, insisted that simultaneous fires across such a large area must have a larger cause: “At that hour,” he commented, “at points hundreds of miles apart, in three different states – Wisconsin, Michigan and Illinois – fires of the most peculiar and devastating kind broke out, so far as we know, by spontaneous combustion.” Citing anecdotal evidence about what materials did and did not burn in extreme heat, and drawing on theories he would peddle in a book entitled Ragnarok, Donnelly concluded that human action had nothing to do with fire susceptibility: “It was the access of gas from the tail of Biela’s comet that burned up Chicago.”

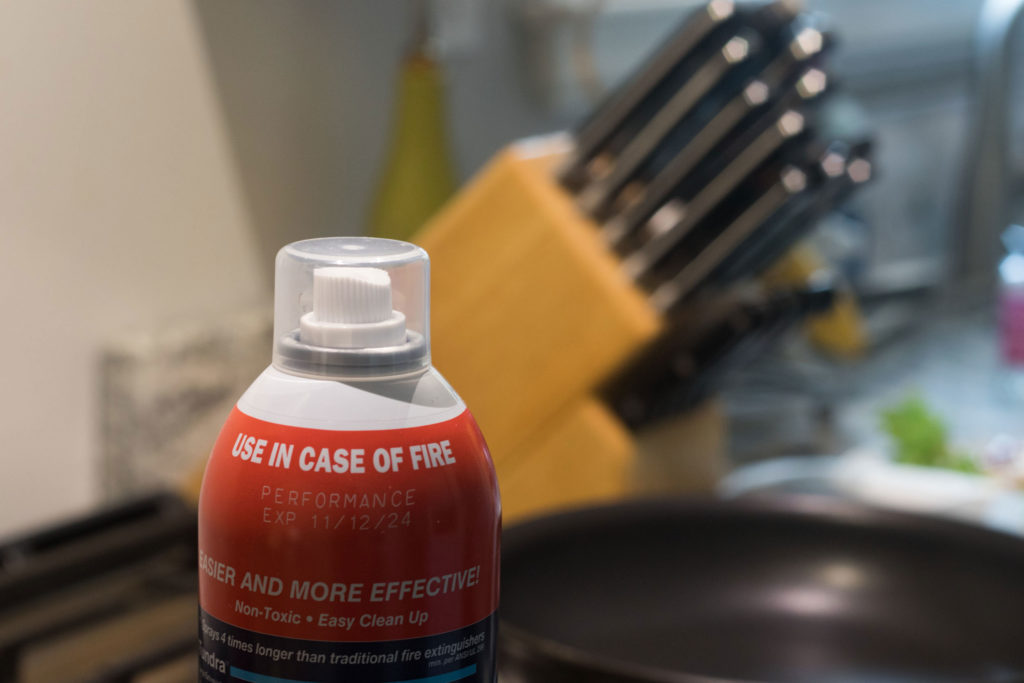

The fact of wildfire is itself not cause for concern – well-managed fire is agreed to be important to forest health, and modern fires, while horrifying, are not as aberrant as you may think (one author notes that, before the 20th century, it was common for thirty million acres to burn nationwide each year). As fighting wildfire becomes harder and more dangerous today in increasingly dry, populated areas, though, we need to do all we can to prevent fires from becoming unmanageable in the first place. Getting rid of pseudoscience, poorly managed cookouts, and explosive pregnancy parties would be a start.

Fun Facts:

Donnelly also thought a comet had been responsible for the Biblical flood, that Francis Bacon wrote Shakespeare, and that the descendants of Atlantis could be found in modern-day Ireland (it’s the red hair, don’t you know).

Fire was such a frequent threat in 19th century cities, and insurance companies so insufficiently funded to deal with the losses, that the development of improved firefighting skills and tools was all but necessary. The antebellum years saw the development of things like fire alarms, steam engines, paid firefighters, and building fire escapes. The insurance industry was tightly wrapped up in firefighting at this time: sometimes insurers would even offer a bonus for whichever fire company could get “first water” on an insured property.

People have tried to lobby to re-name the area that Mark Twain torched after the author, as “Samuel Clemens Cove.” Problem is, no one can quite agree exactly where it was.

Additional Reading:

Ignatius Donnelly, Ragnarok: the age of fire and gravel (1883)

Chad Hanson, “The Myth of Catastrophic Wildfire: A New Ecological Paradigm of Forest Health,” John Muir Project

Wisconsin Historical Society, “Peshtigo Fire”