Have a drink with: You. Just have a drink.

2021’s off to a start, huh?

Talk about: What wine goes with an attempted coup?

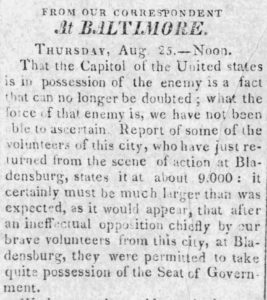

Yesterday’s breach of the United States Capitol by a shaggy horde of insurrectionists egged on by the President of the United States was a historical anomaly of the worst kind: the first intrusion into the Capitol by an unwelcome force since the British invasion of Washington during the War of 1812. In the late summer of 1814, British forces tore through the District and laid waste to government buildings, including a fiery effort against the still-incomplete Capitol building.

On August 24, 1814, as frantic residents and government personnel in the District packed up everything they could carry on threat of British invasion (Dolley Madison doing her best to save Washington’s portrait), English forces were dealing the Americans an absolute thrashing in Bladensburg, Maryland, just north of the city. The rout in Maryland cleared the way to Washington, and General William Winder had hard choices to make. His retreating troops were tired, angry and over a barrel, and Winder decided not to attempt to hold the Capitol. “To make a last-ditch stand inside the Capitol or any other enclosure in Washington ,” wrote author Anthony Pitch, “would have bottled up his men, allowing the British to starve them into submission while giving the invaders a free hand to subdue the rest of the city.” They figured on maybe being able to fight back from higher ground in Georgetown.

The Capitol was, to modern eyes, then unfinished: construction had largely stopped at the outset of the war, and the two legislative wings were connected by a long, unpainted covered wooden walkway. (The building also then housed the Library of Congress and the Supreme Court.) Entering the House chamber, British soldiers attempted to fire rockets through the roof, and when that did not work, they piled wooden furniture in the center of the chamber and smeared it with gunpowder paste before making a bonfire.

As fire spread, Pitch writes, “the British had to work harder on their destructive swath downstairs, where there was less furniture and no wooden platform to kindle the flames. They pulled out window frames, shutters, and doors, chopped them up with an ax, emptied the contents of rockets into buckets, and spread the flammable mix onto the woodpile. It took time and was haphazard, with the result that some wood survived unscathed in every room.”

The English admiral George Cockburn, ranging through various House offices as his forces wreaked havoc, found a leather-bound volume embossed “President of the U. States” on a desk in an executive office. He decided to take the volume – Madison’s copy of the federal finance accounts – as a souvenir, and later inscribed it with a proud note that he had plucked it from the President’s own room.

The war continued, and the British moved on to attempt taking Baltimore, but were held off in September as bombs burst in air over star-spangled Fort McHenry. Peace discussions towards the Treaty of Ghent were already underway, and with good reason: by the winter of 1814-15, the economy sucked because of blockades, New England threatened to leave the Union, Andrew Jackson held New Orleans, and Canada just wanted to be Canada, thank you very much. The Treaty of Ghent was signed around Christmas, and was ratified by the United States the following February, ending the war.

A rainstorm, along with its designers’ choice of structural materials, saved the Capitol from complete destruction that violent night. With Madison’s authorization Congress met in the interim in the U.S. Patent Office, housed in a local hotel, and remained in various temporary quarters until the Capitol was again ready for use in 1819.

Fun Facts:

A much-circulated image over the past day has shown one of the insurrection members walking through the Capitol, carrying a Confederate flag. The image, in supreme You Cannot Make This Up-ness, captures this man strolling between the portrait gazes of Charles Sumner, noted abolitionist and target of the 1856 Congressional caning incident, and asshat slavery apologist John Calhoun.

And by the way, that isn’t a Confederate flag. The banner of that design was one of many battle flags used by Confederate soldiers to distinguish themselves from Union troops on the field of battle, and was largely associated with the Army of Northern Virginia. The flag was revived in usage and symbolism in the 20th century by veterans’ organizations, politicians and right-wing activists in order to support segregationist politics and stand against civil rights efforts.

The iconic Capitol dome, which calls to mind St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, was not added to the building until the middle 19th century.

There have been a small number of unwelcome intrusions into the Capitol over the years, but most have been smaller-scale, isolated incidents involving no more than a handful of assailants threatening targeted violence.

Additional Reading:

Architect of the Capitol, “A Most Magnificent Ruin: The Burning of the Capitol during the War of 1812“

Library of Congress, “Sketch of the march of the British Army under Gen’l Ross from the 19th to the 29th August 1814“

Anthony Pitch, The Burning of Washington: The British Invasion of 1814 (1998)

John M. Coski, The Confederate Battle Flag: America’s Most Embattled Emblem (2006)