Have a drink with: Vinegar Valentines

You’re awful; I love you

Ask them about: Negging in the Victorian era

Is Valentine’s Day not for you? Are you sick to death of hearts and teddy bears? Can Starbucks shove its molten chocolate latte up its molten mermaid tail? Are you looking for something that more befits the holiday in our modern age, but maybe short of actually cheering for gangland murder?

Search no more, for here to the rescue is the heartless Internet troll of the 19th century: the insult comic valentine.

As long as there have been people on the planet, there have been love notes. But the Valentine as we know it is a relatively recent invention, generally traced to one Esther Howland, an enterprising young Mount Holyoke grad who in 1847 was charmed by a Valentine card from Great Britain and persuaded her father (who owned a stationery business) not only to order some from overseas, but to offer cards of her own creation. Howland’s lace-paper cards sold like hotcakes – before long Esther was doing six-figure business and had set up an assembly line of women to produce cards by the thousands (suck it, Henry Ford!).

That would be a sweet story of blossoming love and female entrepreneurship if it ended there, but once Valentine’s Day became the object of public and commercial enthusiasm in the mid-19th century, things changed a little bit and it wasn’t all lace paperwork and cute acrostic poems.

Enter “vinegar valentines” or “comic valentines” – caricatures with cutting insult verse, sent to “fusty old bachelors and sour old maids that are beyond cure,”* frenemies, enemies, as gags and, in the spirit of modern Internet commentary, to be just plain anonymously mean.

They were produced more cheaply than “sentimental” valentines like Howland’s, which were touted in advertising for their craftsmanship and materials (and, indeed, the rise of the commercial Valentine’s holiday in the Victorian era goes hand in hand with the rise of advertising and marketing culture; just ask our friend P.T. Barnum) – most were mawkish caricatures printed on thin paper, so they don’t survive in the same capacity or condition as “nice” ones.

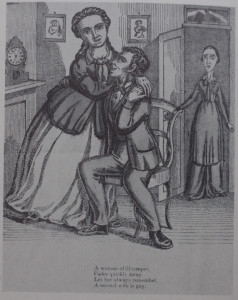

Or, maybe people didn’t save them because THEY ARE HORRIBLE:

A woman of ill temper,

Fades quickly away

Let her always remember,

A second wife is gay.

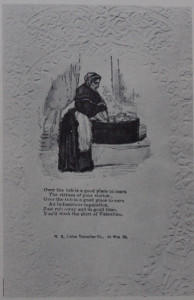

Over the tub is a good place to learn

The virtues of your station,

Over the tub is a good place to earn

An industrious reputation.

Just rub away and in good time,

You’ll wash the shirt of Valentine.

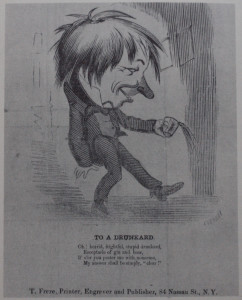

Oh! Horrid, frightful, stupid drunkard,

Receptacle of gin and beer,

If e’er you pester me with nonsense,

My answer shall be simply, ‘clear!’

Was it just pure spite? Well, mostly – but there’s also a very cruel Victorian sense of policing decorum, of using these as an anonymous, passive-aggressive way to point out, shame and correct someone who’s so gauche as to behave improperly. In the worst way, they reinforce a very strict and specific code of social mores – cards talk about drunkenness, grooming, being cheap or impolite, not complying with women’s gender expectations (shame on uppity women and henpecked men), or even about behavior within a profession.

So just in case the present political climate and state of human discourse has you thinking that humanity has surely gone downhill in morals and kindness since the good ol’ days of yore: maybe not as much as you think. XOXO.

Fun Facts:

The double burn, as Collectors Weekly notes, is that in the 19th century, people didn’t purchase postage but generally paid upon receipt of mail – so recipients would pay for the privilege, so to speak.

If this is all too harsh, you could always go ancient Roman on the holiday and try Lupercalia – a Roman festival celebrated mid-February in which men would run around in their skivvies slapping women with strips of the skin of a freshly-sacrificed goat, to increase fertility. We get the name “February” from the goat-skin pieces, or “februa.”

As with many holidays that have been alternately hybridized, commercialized and Christianized, Valentine’s Day became a mish-mash of rituals and greetings: drawing names from a jar to select one’s Valentine continued well into the modern era (with fewer goat-related obligations, natch); St. Valentine was brought into the mix to legitimize the holiday; marriage politics, stationery sales, etc.

You’ll see comic valentines called “penny dreadfuls” but this is a misstep – that term refers to cheap pulp thriller stories published in the same time period.

Even though it’s like eating a squeaky piece of candied chalk, I’m from New England so I have to rep for NECCO candy. The chocolate wafers are the best. (NECCO is also an 1840’s invention, and wafer-candy messages showed up in the 1860’s – though the “conversation” sweets weren’t heart-shaped until the 20th century).

Shout-out to Ludo for the “Love Me Dead” reference up top…

Additional Reading:

Ruth Webb Lee, A History of Valentines (1952)

* Leigh Eric Schmidt, The Fashioning of a Modern Holiday: St. Valentine’s Day, 1840-1870, Winterthur Portfolio (Winter 1993)

The Library of Birmingham and Slate Vault on comic valentines

The American Antiquarian Society on Making Valentines: A Tradition in America and Esther Howland