Have a drink with: Marie Tussaud

Utility, amusement, severed heads.

Ask her about: working motherhood

Looking forward to Halloween, I’m at Atlas Obscura today writing about Madame Marie Tussaud, the 19th century entertainer and artist who got her start making death masks of decapitated French revolutionaries. Marie left France at forty years old, with her toddler and a bag of wax heads in tow, ready to bet on a new life (one that did not include her husband, who she’d as soon have smacked with a two-by-four). She knew that the public loved two things – royal tabloid news and bloody Victorian crime – and she gladly obliged with newer and better attractions every year, parading a collection of wax notables around England and Scotland for twenty years before settling in a sprawling London gallery. She died in 1850 with credit for Britain’s most popular tourist attraction, an institution that in intervening years has given rise to a collection of two dozen global wax museums.

Click over to Atlas Obscura to read the whole story. Meanwhile…

Fun Facts:

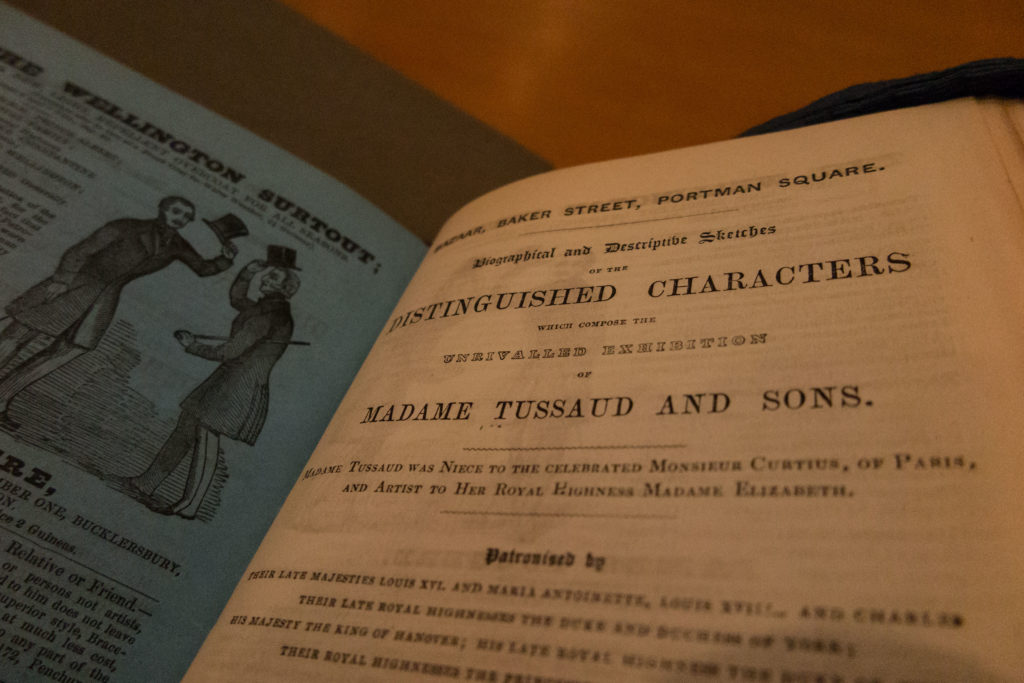

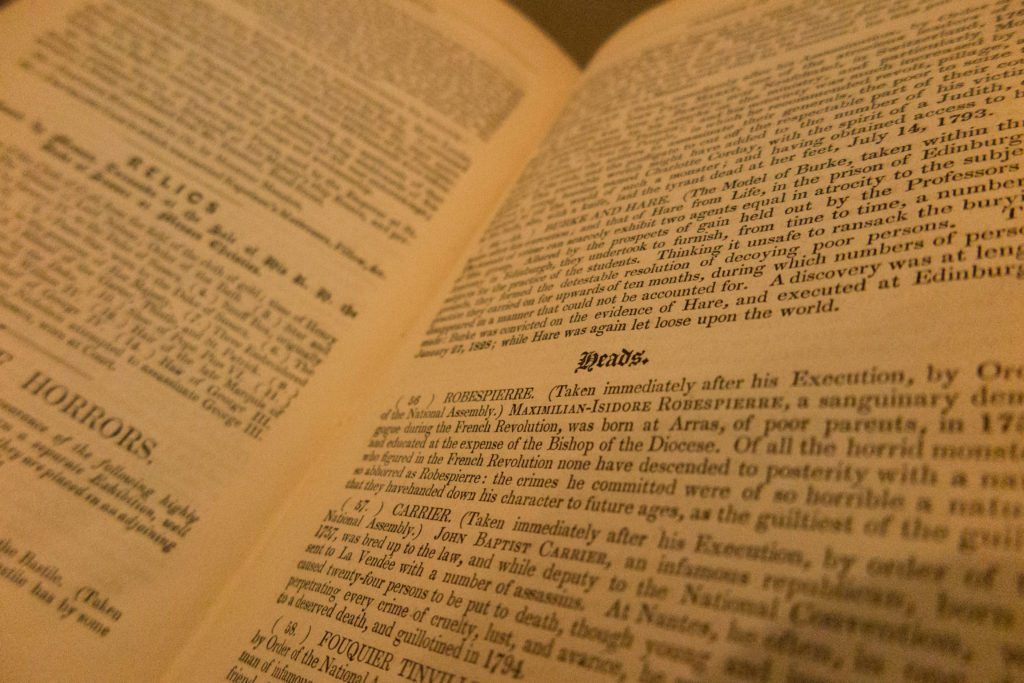

In an 1848 exhibition catalog, the copy notes that “In consequence of the peculiarity of the appearance of the following highly interesting Figures and Objects, which form a separate Exhibition, well worthy the inspection of Artists and Amateurs they are placed in an adjoining room, which represents the interior of the Bastile” (or: we put the gory stuff in a separate room, and whether you call it artistic curiosity or gawking we don’t care – you’re welcome to it. We made it look like the Bastille!).

Replicating the truth of a situation – the precise clothes, a sense of place and atmosphere – was of prime importance to Madame Tussaud, who would use clothing, furniture, accessories and interpretive materials to get the audience into the mood and the moment as much as possible. Napoleon’s displays included genuine coronation robes, swords, a gold watch, dessert service, and even a genuine (“affirmed!”) toothbrush and pair of socks. For scarier exhibits, the room where it happened was key:

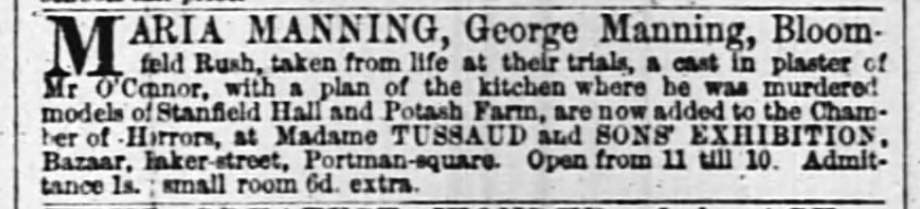

Tussaud’s popularity shone a light, for perhaps the first time, on the possibility of media-driven copycat crime and the normalization of celebrity murder: the fame accorded Rush’s wax figure had a documented influence on later killers including the Mannings. The London Observer on September 10, 1849, in an article about the Manning trial, had an acquaintance explain: “Manning said he thought of going to see the wax figure of Rush at Madame Tussaud’s exhibition, and asked me whether I thought a murderer went to heaven. I replied ‘No.’”

Since Marat died in the bath and had nasty skin problems, the body did not hold up well. It is suggested that the famous painting by Jacques-Louis David of “The Death of Marat” was actually painted from Tussaud’s waxwork rather than from the corpse itself.

The body-snatcher William Burke was fragmented after death. His skeleton remains today at Edinburgh University, there is a book bound in his skin, and he was, in an act of grim poetry, ordered by the judge to be dissected by students postmortem.

Additional Reading:

Betsy Golden Kellem, “How the Real Madame Tussaud Built a Business Out of Beheadings,” Atlas Obscura, October 10, 2017

Pamela Pilbeam, Madame Tussaud and the History of Waxworks (2006)

Paris Amanda Spies-Gans, “‘The Fullest Imitation of Life’: Reconsidering Marie Tussaud, Artist-Historian of the French Revolution,” Journal18, Issue 3 Lifelike (Spring 2017)