Have a drink with: The Charles W. Morgan

Whaleship, world traveler, cultural ambassador, marine rendering plant

Ask her about: What it smells like to cart around a few dozen sailors in a wooden oil tub with limited cleaning facilities. For three years at a time.

The Charles W. Morgan is the last of the American wooden whaling ships, originally built in 1841 in New Bedford, Massachusetts and retired in the early 20th century after an active whaling career. Normally a floating exhibit at Mystic Seaport, the Morgan has undergone a multi-year, multi-million dollar restoration and is right now under sail around New England for the first time since the 1920’s. She’ll travel from Connecticut to Newport, New Bedford, Cape Cod and Boston before returning home in August, and you can follow the voyage on the Seaport’s various great online and social media streams (hashtag: #38thvoyage).

Now, I love history, but I REALLY love whaling history. To the point that I did a summer internship at a whaling museum while in law school. (Tax law memos or scrimshaw? Duh.) But if you are not me, and chances are you aren’t, what is this Morgan thing all about?

I thought you’d never ask.

In modern conservationist culture whales have come to symbolize both the plight and purity of the environment, and opposition to whaling is so broadly accepted as to be essentially a social norm. In the 19th century, though, whaling was the engine of the world economy, feeding a massive commodities market for whale oil and related products, and whales were regarded as an exploitable resource.

“Death to the living, long live the killers, success to sailors’ wives and greasy luck to whalers.”

– Whaler’s proverb

American whaling rose to its highest point in 19th century New England (especially the antebellum years), when Nantucket and New Bedford dominated the industry and the latter was called the “city that lights the world.”

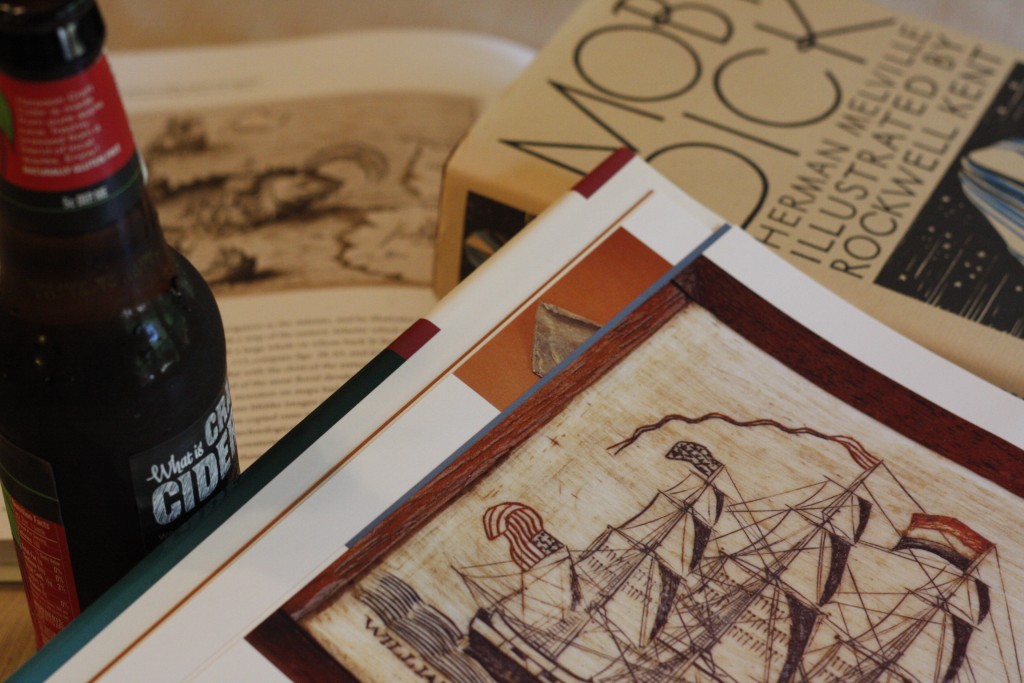

Whaling voyages were difficult trips on squat, hardy square-rigged wooden ships that, frankly, Did Not Smell Good. Voyages could last three or more years at a time and didn’t make the average sailor much (if any) money – the commercial yield from whale oil and spermaceti was astonishing, but the bulk of the money went to owners, agents and others more senior to the typical whaleman. Whaleships were built for long-term utility and high commercial yield, which meant that long trips and full holds were best for business. Herman Melville explained whaling’s payroll system in Moby-Dick:

“I was already aware that in the whaling business they paid no wages; but all hands, including the captain, received shares of the profits called lays, and that these lays were proportioned to the degree of importance pertaining to the respective duties of the ship’s company. I was also aware that being a green hand at whaling, my own lay would not be very large; but considering that I was used to the sea, could steer a ship, splice a role, and all that, I made no doubt that from all I had heard I should be offered at least the 275th lay — that is, the 275th part of the clear net proceeds of the voyage, whatever that might eventually amount to. And though the 275th lay was what they call a rather long lay, yet it was better than nothing; and if we had a lucky voyage, might pretty nearly pay for the clothing I would wear out on it, not to speak of my three years’ beef and board, for which I would not have to pay one stiver.”

The Charles W. Morgan made thirty-seven voyages in her working lifetime.

Whaling was a high-risk profession as well, since the process required harpooning the animal from small whaleboats at a distance from the main ship, towing it back and then stripping the carcass aside the ship for onboard processing into barreled oil.

Whaling expanded its geographic scope as whalers exhausted ocean grounds on their long trips and moved on to find regions still populated by whales. The industry diversified main whaling ports with the arrival of international sailors, and facilitated exploration of and cultural exchange with distant areas of the globe. During the height of Yankee whaling, it was not unusual for a trip to sail from New England to the Azores (known for its boatmen), down the Atlantic and around Cape Horn – bound for the South American coast and ultimately Polynesia or the Pacific Arctic.

According to one history of 19th century whaling, the pre-Civil War years “brought phenomenal growth, with over six hundred vessels at sea each year on average until that year, bringing or sending home eight million dollars’ worth of oil and bone each year…At least sixty grounds were in the vocabulary of whalemen of experience; it is difficult to find any corner of the world’s oceans that was not explored, and any assertion to the contrary is dangerous.” *

After the Civil War, the whaling industry recovered but never again attained its prior greatness. Many factors hurt profitability, including the availability of other fuels, as well as the difficulty of whaling in those remaining grounds with viable populations. Horrifyingly efficient modern whaling technologies – fast, fuel-driven boats and exploding harpoons – drove the wooden whalers into irrelevance.

Richard Ellis writes in his book Men & Whales:

“The last of the square-rigged Yankee whalers to set out in pursuit of whales was the bark Wanderer, which departed from New Bedford on August 25, 1924. She encountered a fierce northeasterly gale, ran aground and was wrecked on the rocks at Cuttyhunk Island on the following day.”

Perhaps to atone for that clumsy anticlimax, ninety years later a wooden whaler sails again.

Fun facts:

“Down to the Sea in Ships” is a silent movie filmed on real ships at the tail end of wooden whaling. One of actress Clara Bow’s first vehicles, it features the Morgan.

In the movie “Master and Commander,” Russell Crowe’s character at one point orders the ship to set a fire burning on deck to create the impression to distant ships that they’re a whaler. It’s unlikely that any experienced sailor would fall for that trick for long, since whaleships are “uglier” than square-rigged warships – they needed cargo space and carriage for whaleboats, so they were fat and studded with boats.

Since the mid-1980’s ban on commercial whaling, only a handful of nations (including Japan, Norway and Iceland) continue the practice, usually citing a mix of scientific, cultural and political reasons. The International Whaling Commission permits a certain amount of susbsistence whaling for Native peoples.

When harpooners struck a whale, the panicked animal would often swim quickly away, with the boat in tow. This is what whalers called a “Nantucket sleigh ride.” Like tubing, but with an angry whale instead of a speedboat.

To read:

Track the Morgan and watch a great video about its restoration thanks to the folks at Mystic Seaport.

For background material on the whaling industry, see, e.g., *Briton Cooper Busch, Whaling Will Never Do For Me: The American Whaleman in the Nineteenth Century (1994 ) and Elmo Hohman, The American Whaleman (1928).

In addition to its esteem as a work of American fiction, Melville’s Moby-Dick is remarkably accurate in its depictions of whaling practice, thanks in part to the author’s time aboard ship in the 1840’s.

A great article from the Atlantic talks about the rise and fall of whaling – I personally think there’s a lot more to the decline of the industry (rise of alternative whaling weaponry and demand cycles, various wars, the parallel ups and downs of the American textile industry, etc…), but enjoyed reading this.

A New York Times report on the Morgan from October 30, 1900.