Have a drink with: Thomas Nashe

It was the merry month of February…

Ask him about: Valentine’s Day plans

Though he lived in Elizabethan England, Thomas Nashe was not an unfamiliar figure to modern thinking: in his twenties, Nashe was out of college, short on funds and trying to make it as a writer in London. It was a tough time for a writer without independent wealth or consistent patronage – plague outbreaks made life dangerous and, as a practical matter, often closed the theaters that called on writers for material. And while young Thomas was very talented, let’s face it: when you’re a freelance writer, no matter how good you are sometimes you’ve just gotta pay the bills. Sometimes having to “prostitute my pen in hope of gain” means writing corporate sales copy, sometimes it means ghostwriting, and yes, sometimes it means reluctantly writing raunchy poems about sex toys. Welcome to the Elizabethan Cialis ad.

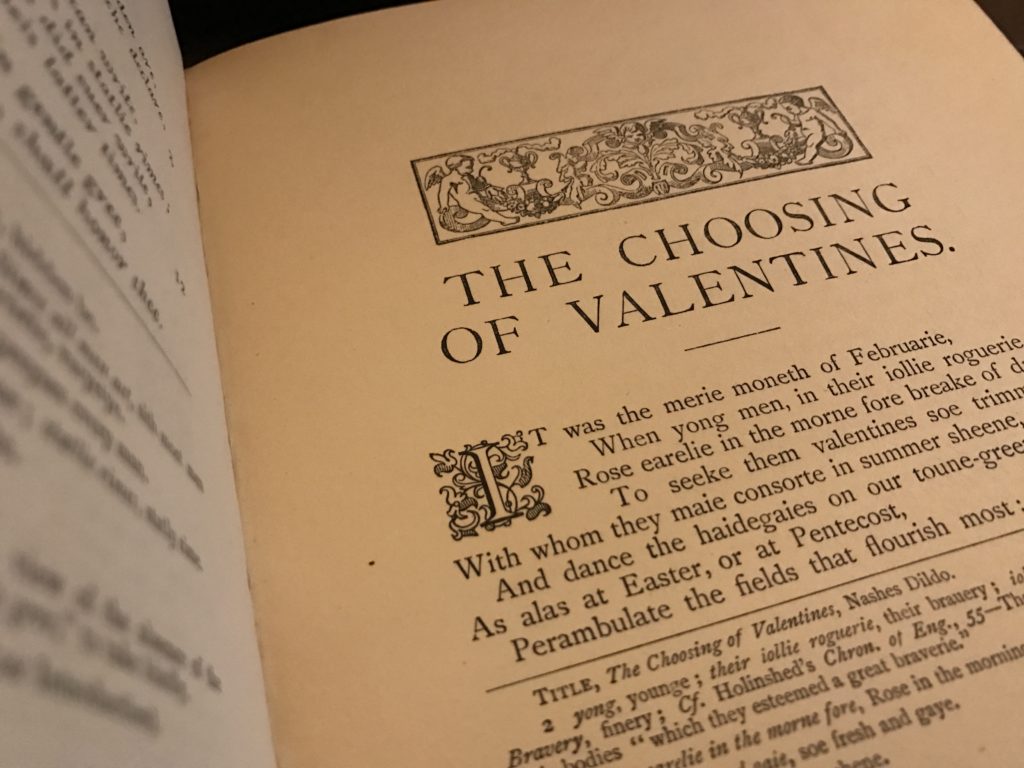

Written for the dashingly named Ferdinando Stanley, aka Lord Strange (seriously, someone give this man a comic book), Thomas Nashe’s The Choise of Valentines might have been a forgotten dirty poem but for one particular notable: in writing his saucy story, Nashe ended up coining the word “dildo.”

Here’s the story. It’s Valentine’s Day, and our main character Tomalin is looking for his lady Francis, who he finds has unfortunately left town and taken up at a city brothel. He finds the place and is thrilled to see her – frankly, a little too thrilled, and ends up being of very little use to Francis, who had thought ahead and ordered, uh, assistance. Tomalin is upset at his surrogate and, red-faced, he pays and leaves.

Commentary about Nashe’s flowery Valentine is all over the place, with many unanswered questions: is the brothel representative of misogyny or women’s sexual freedom? Is Francis actually devoted to Tomalin, or is he deluded and pining? Is this all this emasculation stuff just displaced national anxiety over Elizabeth on the throne, or is it because society had not yet produced ED advertisements with foxy gray couples in inexplicable beachfront bathtubs? Can pearl-clutching critics (some of whom tried to disavow that Nashe even wrote this) really stick to the idea that “serious” artists don’t write smut?

There are interesting gender and social issues at play in the poem – while Tomalin enters the story with bluster and boorish insistence, calling the madam a triple-chinned fatty and insisting on seeing the youngest, prettiest girl in the house, Francis has the upper hand. She plainly demonstrates that for all their social dominance, guys used to social bossery are nonetheless full of performance anxiety; and, in proclaiming her faithfulness – “but thy self true lover have I none;” and “for shelter only, sweetheart, came I hither” – points out the man’s gullible devotion (since presumably he believes both of those lines).

Or, more to the point: “As for being demeaning to women: yes, on one hand, the female character exists in the poem primarily as a sex object and in the name of fuelling the bawdy narrative. But then, so does the man; and the man, whom the subtitle invites us to consider as the poet and not as wholly fictional, is crucially not even a successful sex object.”*

Happy Valentine’s Day.

Fun Facts:

Shakespeare would use the term “dildo” a couple decades later in The Winter’s Tale, but Nashe gets the prize for first use in English, with the manuscript thought to date to about 1592/3.

Like Fanny Hill, Nashe’s poem has been around for centuries but originally existed only in manuscript copies (some of which vary on the details). The poem survived covertly through passed-around copies until 1899, when a London publisher printed the work on a limited basis – “for subscribers only.”

There are academic challenges when delving into the more vernacular works of early modern Europe: “Twenty-first-century scholars may be untroubled by bawdy, yet are, I suspect, much less comfortable with relentless jokes about farts and turds – or may simply not know with what tools to analyse them.”

Even psychologists can’t figure out the bathtubs: “The couple appears to be naked, each in one bathtub. The tubs are separated– the couple is holding hands. I guess the implication is that these attractive older folks have successfully done the deed and now they’re in a relaxed post-coital state. The bathtubs are not in a bathroom, or even a spa. They have no plumbing. They are in the middle of nowhere logical. The viewer isn’t sharing the couple’s satisfaction, s/he is thinking BUT WHAT DO THE BATHTUBS MEAN? WHAT DO THEY SIGNIFY?”

Additional Reading:

Thomas Nashe, The Choice of Valentines (annotated) (text)

* Adam Crothers, A Disappointing Valentine?, St John’s College (Cambridge) Library blog,

Katherine Duncan-Jones, “Nashe’s ‘Choise of Valentines’ and Jonson’s ‘Famous Voyage,’” The Review of English Studies, New Series, Vol. 56, No. 224 (April 2005)

Ian Frederick Moulton, “Transmuted into a Woman or Worse: Masculine Gender Identity and Thomas Nashe’s ‘Choice of Valentines,’” English Literary Renaissance, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Winter 1997)