Have a drink with: The 19th Century Anti-Gun Lobby

“We’re all hot at the same time, and we should do somethin’ about it!”

Ask them about: Background checks

If you watch enough movies – Civil War dramas, Wild West adventures, Five Points gangland brawls, Mel Brooks – you’d be forgiven for thinking that the 19th century was one long festival of unmitigated gun violence.

Indeed, in the 1800s, industrialization was the catalyst for mass production and ownership of guns. Prior to that, gun ownership was relatively rare and despite a romantic ideal of the American militia, apparently most of them literally couldn’t hit a barn door.

But what might surprise you is that the American reputation for a history of unchecked gun culture is, on the whole, undeserved. In the 19th century concealed carry prohibitions were common – and serious.

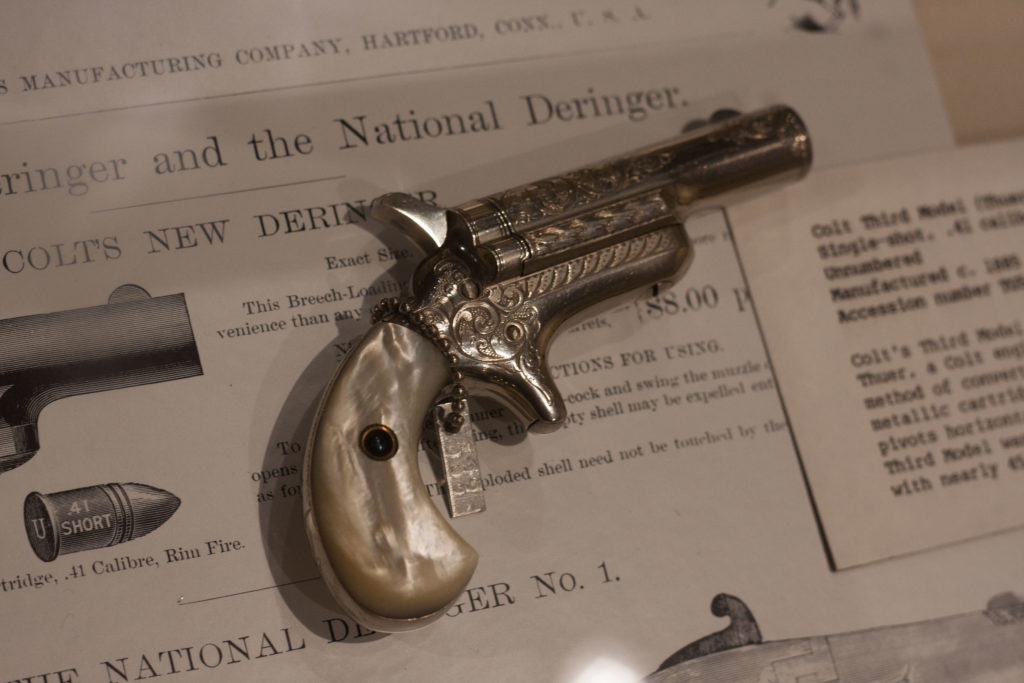

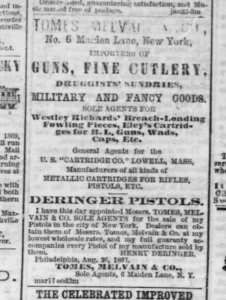

In the 1800’s manufacturing made pistols readily available, advertising made them desirable to middle-class men, and design made them conveniently tiny (The “Philadelpha Deringer,” a mid-century pocket pistol remembered today by the misspelling “Derringer,” was John Wilkes Booth’s weapon of choice at Ford’s Theater).

The American South led the nation in concealed carry laws, realizing that the regional penchant for eager defense of one’s honor could result in some hideous cleaning bills if every Tom, Dick and Harry suddenly had a pistol on his person. Kentucky and Louisiana led the way in 1813, with other states following through the antebellum period. Requiring folks to turn in their guns for a coat-check token of sorts, writes law professor Adam Winkler, “Frontier towns handled guns the way a Boston restaurant today handles overcoats in winter.”*

People thought concealed weapons not only volatile but unmanly: only a coward would hide his weapon.

In the 1850’s, guns and bladed weapons accounted for less than half of New York City murders, most killers opting for convenience rather than specific tools (“most murderers used whatever was handy, including hands, feet, sticks, rocks, chairs, and combinations of them all.”**). But while guns didn’t account for a majority of murders by any means, they (along with their owners’ motives) were more easily hidden, and more assuredly lethal if used.

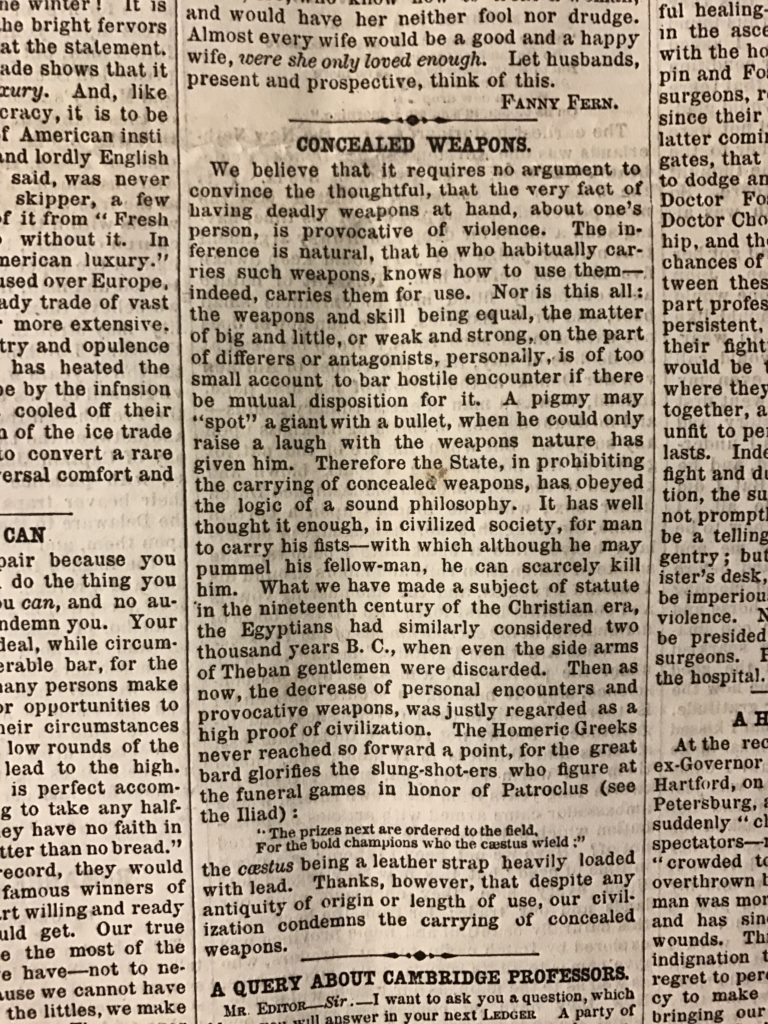

The New York Ledger took up the issue of gun control on its October 1, 1859 op-ed page, expressing prim horror at the idea of good citizens carrying firearms on the streets of New York. And from this we can derive the real lesson: Why carry a gun when you can beat the piss out of someone like God intended?

Pummel away.

Fun Facts:

Just ask Eddie Izzard: “guns don’t kill people, people kill people – but monkeys do too! If they’ve got a gun.”

The New York Ledger was a very successful New York paper, known for its serials and its star columnists. “Fanny Fern” was the pen name of Sarah Willis, a popular novelist and writer who advocated for women’s independence and insisted on $100 a column, and who of course was therefore criticized for “certain bold, masculine expressions that we should like to see chastened.” Others called the talented Fern “a charming little humbug…she ought to have married Barnum.”

(No, not the Ledger you’ve seen on TV.)

The Ledger’s column talks about weapons prohibition as a mark of high civilization, pointing to ancient Egypt. Japan is perhaps an even better example – Noel Perrin’s excellent short book Giving Up the Gun talks about the nation’s decision to experiment with and then de-emphasize guns. Despite manufacturing excellence, Japan came to consider guns a “lower-class” weapon to be used by farmers or less trained warriors, since they deprived fighters of individualized combat, de-emphasized skill and bravery, and were often unreliable in poor weather. The sword was revered as both beautiful *and* useful within the samurai warrior class, who constituted a far higher percentage of the population than in any other country at the time; and there was also a strong Japanese skepticism of foreign intrusion. Not until Commodore Perry were guns made part of the culture significantly again.

In October 1824, Thomas Jefferson sat in on a board meeting to draft the student handbook for the new University of Virginia, and it included limits on campus carry: “No student shall, within the precincts of the University, introduce, keep or use any spirituous or vinous liquors, keep or use weapons or arms of any kind.” (The board’s rules also extended to limits on a student engaging in “festive entertainment,” “disturbing noises in his room,” and “riotous, disorderly, intemperate or indecent conduct.” So: college.)

Additional Reading:

The New York Ledger, October 1, 1859

Noel Perrin, Giving Up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1543-1879

* Adam Winkler, Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America (see also at HuffPo)

** Erik Monkkonen, Murder in New York City