Have a drink with: Abdul Karim

The jewel in the Crown

Ask him about: Royal language lessons

The movie Victoria and Abdul portrays the relationship between Queen Victoria and Abdul Karim, a young Indian man assigned to her service in the late 1880s. Karim, originally a clerk from Agra, India, came to Victoria’s service during her Golden Jubilee in 1887. He became a favorite friend and confidante, acting as the Queen’s Urdu language teacher and Indian secretary, much to the frustrated jealousy of the royal household.

Victoria had a complicated relationship with India: on the one hand, she was fascinated with and fetishized all things Indian – learning Urdu, bringing curries onto the regular dining rotation at the palace, and decorating an entire lavish chamber at her Osborne House with Indian arts and architecture (including a lavish portrait of Karim himself, alongside paintings of Indian craftspeople). On the other hand, the allure doesn’t change the fact that she was the ruler of a forcibly and uncomfortably subdued nation of people whose welfare wasn’t permitted to muddle the interior decorating. It’s hard to know for sure whether Abdul Karim was a proxy for Victoria’s general fascination with exotic India; a genuine friend who provided the added benefit of making her stiff-necked family crazy; a subservient target for the Queen’s romantic or maternal impulses; or something else entirely.

Nor is the movie the first time Western voices have been the ones to comment on Abdul Karim’s story, or his status as what writer Bilal Qureshi called “Manic Pixie Dream Brownie.” Karim was no stranger to news media at the time, and American papers particularly covered the fact of his employment with condescending, starchy amusement – like, look at the Queen learning the funny Eastern language! She has an Indian tutor! Just a few of the winning clippings:

Were Other Adjectives Not Available?

Harrisburg Daily Independent, December 6, 1893

Victoria provided amply for the Munshi (an honorific for “teacher”) and his family: she granted him residences in England and land in India, had his family brought to England, allowed him the right to wear a sword and generally set an example of respect and station that everyone else had to (if grudgingly) acknowledge. One of the Munshi’s homes was a cottage at Frogmore, an estate within the purview of Windsor castle. An article showed Princess Victoria Eugenie on her 6th birthday, sitting happily on Karim’s elbow. “Her majesty is constantly finding some new occasion of showing her regard for her oriental attendant, the latest mark of her favor being to give him and his wife a pretty cottage and garden at Frogmore for their occupation. As the cottage is within a stone’s throw of Frogmore House the children of Princess Henry of Battenberg will have their dusky friend quite at their beck and call, and will be able to exercise over him that childish despotism to which he, like most strong men, is so ready to submit.”

“He’s Leaving to Spend More Time With His Family…”

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 27, 1901

When the Queen died, her son “Bertie” – now King Edward VII – had a clear path to get rid of the man whose presence in his mother’s affairs had irked him for so long. With a clutch of guards in tow, Bertie banged down the Munshi’s door, had all of his correspondence with the late Queen burned, and in no uncertain terms told Karim to pack up and move back to India. This dismayed England’s Indian ex-pat population, who made their sentiment known to the news media:

“Abdul Karim, C.I.E., C.V.O., Indian secretary to Queen Victoria, has received an illuminated address from his co-religionists in London. The document, after congratulating him upon the high distinction conferred upon him by the late Queen, expressed the sincere regrets of his compatriots at his retirement from a position where he had been of service to his sovereign and country.”

You can just imagine the air-quotes around the word “retirement.”

They’re prejudiced, all right. Towards, you know, flavor?

Los Angeles Times, September 10, 1893

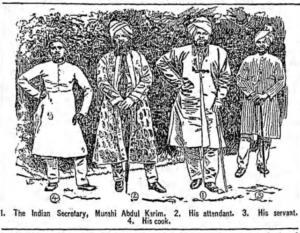

Noting that “Her Majesty’s Indian empire is represented in her household,” the Times’ profile of Victoria’s various and notable servants (largely focused on John Brown, who is described not unlike a particularly devoted pet spaniel, if dogs wore kilts) mentions the Queen’s four Indian attendants in residence – Karim, along with a personal attendant, and their servant and cook. “A special part of the castle is assigned them, where are their kitchen and other apartments. Their food is prepared by their own cook in accordance with Hindoo customs and prejudices. The atmosphere of their portion of the castle is said to be redolent of curry.”

If you just speak louder and slower, everyone understands English.

The San Francisco Call, October 7, 1892

The English may have liked the idea of empire, and enjoyed the benefits of Indian resources (Indian “ayahs,” or nannies, were suddenly common accouterments to traveling British households), but still considered the nation wholly inferior.

“Since 1888 her Majesty has been a diligent student of Hindustani, and that study has been coterminous with the employment of Munshi Abdul Karim as secretary to the Queen…Few there are who learn Hindustani from pure love of the study, but her Majesty has shown a quite remarkable zest to acquire the language, and is, it need scarcely be said, the only British monarch who has attempted it.”

Orientalism! < jazz hands >

Lincoln (Neb.) Evening News, April 20, 1900

The Munshi is described on a page with such curiosities as “Fish That Talk,” “A Duchess and Her Donkey,” and “Great Britain’s New Battleship.” Captioned “A Talented Hindoo,” the article calls Karim “One of the most intellectual and most respected foreigners in England at the present day.” “Unlike the ordinary Hindoo,” says the paper, “Abdul Karim is no ascetic.”

Fun Facts:

Author Shrabani Basu notes that over thirteen years of journaling her “Hindustani” (Urdu) lessons, Victoria was devoted to and enjoyed the practice – “The pages entered in it were their own private space, away from the problems of Court, a troublesome family and the ever suspicious and demanding Household. The Queen never missed a lesson.”*

Keep in mind no one had liked Victoria’s companions, from John Brown onward; her family and various political minders generally preferred they be the ones to influence the Queen’s thinking, thank you very much. Whatever the genesis or makeup of her affection, Victoria genuinely stood by the Munshi: the British Library features a particularly horrible example of the sort of dialogue that went around behind her back, a letter cursing Karim as “a thoroughly stupid & uneducated man” with no business being exposed to policy matters. “But it is no use,” says Lord Ponsonby, the Queen’s Equerry (a senior member of her royal staff), “for the Queen says that it is ‘race prejudice’ & that we are all jealous of the poor Munshi.”

Eddie Izzard – who plays Victoria’s son Bertie in the film – still has the best commentary on the British annexation of India.

The Guardian recently featured a piece on American popular culture and the south Asian experience: “In these Trumpian times, the high-profile success of so many talented brown people is a truly heartening thing. However, it’s worth remembering that progress isn’t necessarily linear and that the prominence of minority narratives is often cyclical.

Additional Reading:

* Shrabani Basu, Victoria and Abdul

Bilal Qureshi, “Why Does Hollywood Keep Churning Out Racist Fantasies Like Victoria and Abdul?,” Washington Post, October 9, 2017

Susheila Nasta et al, “Global Trade and Empire, Asians in Britain,” The British Library

“‘Victoria & Abdul’ Explores Colonialism And Islamophobia During Queen’s Reign,” NPR, September 22, 2017