Have a drink with: The Early Birds

There’s only one 10 o’clock in the day, and this ain’t it.

Yell along with them: Go the @%(# to sleep.

In the past week alone, major publications have promised that a good night’s sleep may be the key to successful business, effortless parenting, a better sex life and more enjoyable travel.

That’s all well and good until you consider that some 40% or more of Americans don’t sleep well, despite the assurances that if we deploy the right combination of baths, essential oils, soundproofing, early bedtime and smartphone avoidance, dreamy bliss will follow. So you can take your successful business, Mister-or-Ms. Fancy Journalist, and your perfectly-behaved child, and your one-night stand in Fiji, and get back to me when you have an article on the philosophical ramifications of Netflix asking you if you still exist when you wake up at 1:30 a.m. with no memory of having fallen asleep on the dog.

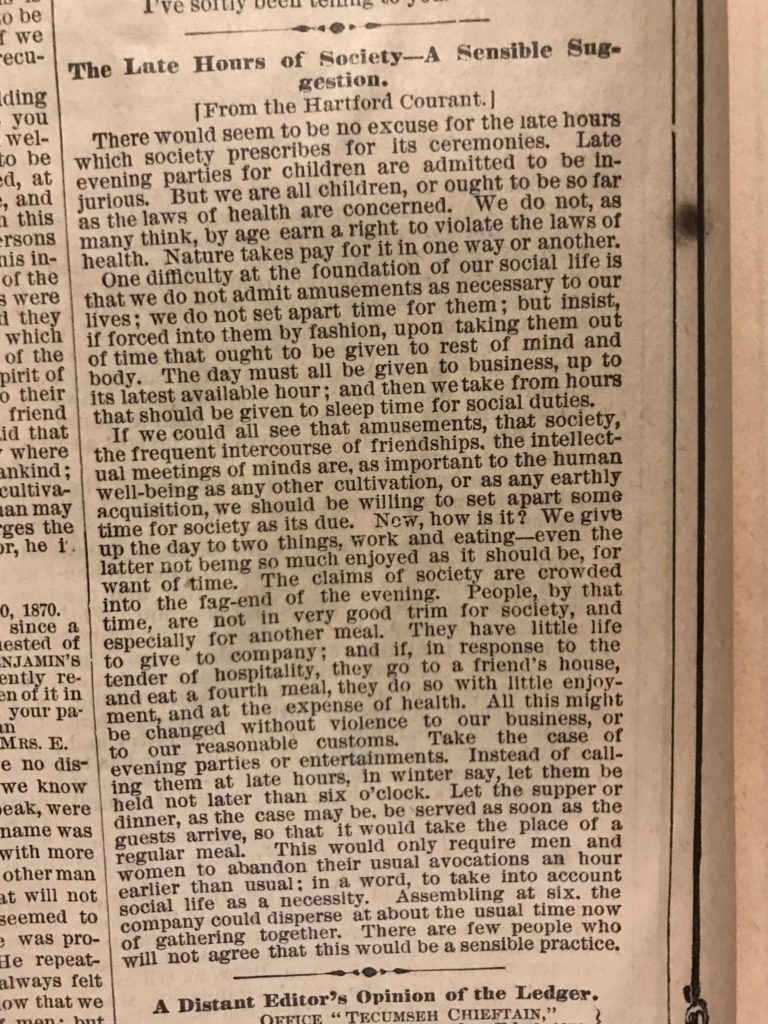

Despite the tossed-off surety that history cannot possibly understand us on this particular anxiety, let’s check in with one brave journalist from 1870 who was worn out enough to suggest: please, folks, please? Can we just start parties at 6 p.m. for a change, and hit the hay early?

Nature, after all, takes pay for it in one way or another.

Fun Facts:

On the hopping 19th century social scene: middle-class women in the middle 19th century were in a bit of a good-news, bad-news situation. They had access to more education and discretionary time than their predecessors. But this broader exposure also meant they had often spent their time learning French or music rather than the traditional household skills then generally passed down by mothers to their daughters. So why simply trade one set of feminine strictures for another, when you can do both? (Sigh.) Enter Mrs. Isabella Beeton’s Book of Household Management, a great how-to doorstop of a book explaining the execution or supervision of all manner of home practices for newly married women, from roasting guinea pigs to hanging the draperies. Beeton was apparently a so-so cook and ganked many of her recipes from other sources; but she was thorough, and did make some very now-trendy recommendations about how to feed a household, favoring use of seasonal produce and encouraging women to make the most of leftovers. She referred to a woman in her home as like “the commander of an army,” the sort of title that does not encourage one to sleep well.

Much has been made of the fact that for most of history people used to sleep in two installments – going to bed at dusk, naturally waking up in the middle of the night for an hour or two, and then going back to bed. (One scholar describes Robert Louis Stevenson blissfully camping in the south of France – after a meal of bread, sausage, chocolate, water and brandy, he goes to sleep, wakes up around midnight to spend an hour simply thinking and smoking a cigarette, and goes back to bed happy and refreshed.*) This “segmented sleep” is well documented into the 19th century, and only after the Industrial Revolution comes into the picture do we start to see socialized efforts to sleep the whole night through. Not coincidentally, around the time we stop seeing written descriptions of segmented sleep, those accounts come to be replaced by the very modern problem of “sleep maintenance insomnia” – or, waking up in the middle of the night and not being able to fall back asleep.

Dinner party manners in the 19th century, also equally applicable today: for Pete’s sake, we’ll all sleep better if you lay off the politics (“Never allow the conversation at the table to drift into anything but chit-chat; the consideration of deep and abstruse principles will impair digestion.”).

Additional Reading:

“The Late Hours of Society – A Sensible Suggestion,” The New York Ledger, March 5, 1870

Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1906 ed.)

* A. Roger Erkich, “Sleep We Have Lost: Pre-Industrial Slumber in the British Isles,” The American Historical Review, Vol. 106, No. 2 (Apr. 2001)