Have a drink with: Presidential Hats

Come at me, bro.

Ask them about: how buff was Teddy Roosevelt?

With the collective American mind very much on upcoming midterm elections, and with a host of new and nontraditional contenders running for office, one phrase pops up perhaps a little more than usual: the announcement that one candidate or another has tossed his or her hat in the proverbial ring.

It’s a common, casual phrase in American English – but where does all this hat-throwing come from?

Perhaps the first public use of the phrase was on November 30, 1804, when the London Morning Post recapped a boxing match between fighters Tom Belcher and Bill Ryan. The sports reporter set the stage for the bout by writing:

“The parties arrived at Wilson Green, soon after ten o’clock, where a ring was formed by the spectators, who anxiously waited the event of the fight. Belcher appeared confident of success, and threw his hat into the ring, as an act of defiance to his antagonist, who entertained the same confidence of success, and received this bravado with a smile.”

(FYI: Belcher was favored in pre-fight betting with 6:4 odds, but went down in the 37th round on a knockout. )

The phrase continues to appear in a boxing context through the 19th century, in American papers as well as in dispatches from London, and in the aftermath of the Civil War it comes to appear in political journalism, with an op-ed in the August 18, 1868 Buffalo Commercial complaining that a certain Wisconsin newspaper had been turned into a mouthpiece for southern propaganda: “On Saturday last it appeared as a Metropolitan organ of the National Democratic Party, and having thrown its hat into the ring, followed close after, exclaiming to the rank and file: ‘I am Sir Oracle, and when I open my mouth let no other Democratic dog bark!’”

By the late 19th century the phase was consistently used not just as a boxing item but as a metaphor within increasingly combative American politics.

Safire’s Political Dictionary credits Teddy Roosevelt for using the idiom particularly flashily in 1912 – and, if we’re honest, it really is the sort of phrase that would seem to delight rough-rider Teddy, himself once a boxer. Though Roosevelt had initially supported William Howard Taft as his successor in the White House, he had over time become disillusioned with the Taft administration and wanted to see more progressive policies enacted. Unable to secure a Republican nomination, Teddy decided to step back into the fray with his own Bull Moose Party, and allegedly said when asked if he’d run for President: “My hat’s in the ring. The fight is on, and I’m stripped to the buff.”

Press from around this time shows that folks were beginning to take the linguistic device literally – and festively! – with one paper noting that “Senator Funk of Illinois, the candidate of the Progressives for Governor, mounted the platform amidst wild cheering and literally ‘threw his hat in the ring.’ He had on an old felt sombrero.”

Though he made an uncommonly solid third-party showing, Roosevelt lost the 1912 election; and so on to the victor: anecdotal evidence says that Woodrow Wilson, on May 8, 1916, attended a performance of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus, and when the band played “Hail to the Chief,” Wilson tossed his hat into the center ring. Reporters took this as an indication of Wilson’s desire to run for re-election.

Like many catchy historical phenomena, whatever its true origin, the phrase became self-fulfilling, and by the later 20th century, literally tossing one’s hat into the ring to kick off a campaign was a symbolic no-brainer: the Circus World Museum in Baraboo, Wisconsin, proudly displays an autographed straw boater thrown into the ring at the Greatest Show on Earth by then-Vice President George Bush in 1988.

Fun Facts:

I’m not sure about the “stripped to the buff” part being more than (highly believable) legend: the New York Sun of February 23, 1912 has Roosevelt responding a bit more demurely, telling reporters that “My hat is in the ring. You will have my answer on Monday.”

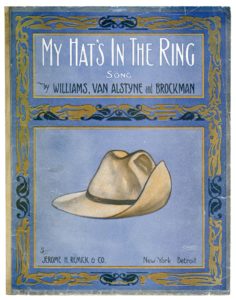

Not to mention, a fair amount of merchandising supports the statement. Not only was there sheet music – “My Hat’s in the Ring” was a popular song written by Harry Williams, Egbert Van Alstyne, and James Brockman to celebrate the candidate’s Presidential campaign – Roosevelt’s chapeau-tossing decision to run in 1912 was echoed in a plethora of campaign buttons, with which supporters could say their hats were in the ring with Teddy’s.

On that 1804 Ryan-Belcher bout: Belcher was a mess in the 36 and 37th rounds, falling “apparently lifeless.” He nonetheless managed to get to his feet, and Ryan then landed a solid blow that ended the fight. At this point the crowd broke up in a general state of disagreement: Belcher’s camp claimed the last punch – struck while their fighter was falling to the mat – was a foul hit, and “consequently he was entitled to the purse.” Ryan nonetheless was declared the victor and received the prize money (13 guineas, about a $1,700 purse today). After the fight, one Bourke, an amateur boxer, “in consequence of a hint, offered to fight any Jew in England for 100 guineas, at a week’s notice.”

Additional Reading:

William Safire, Safire’s Political Dictionary