Have a drink with: Fanny Fern

Reform yourselves, gentlemen!

Ask her about: Menswear styles for fall

“Fanny Fern” was the pen name of Sarah Willis Parton, a popular 19th century writer who advocated for women’s independence, kept her pencil sharp and her wit sharper, and insisted on being paid handsomely for her output: she got $100 a column, making her the highest-paid newspaper writer in the nation at the time, and was therefore criticized for “certain bold, masculine expressions that we should like to see chastened.”

Like fellow 1800s firebrand Delia Bacon, she was educated by Catherine Beecher and came into her adult fame and abilities after exercising considerable survival skills (her second husband was an abusive turd, and she overcame initial rejection and the opposition of her own family to get herself published).

Clear-eyed and honed sharp by the time she began publishing in her forties, Sarah was a dynamo, and did not shy from conspicuously poking at any hypocrisy or injustice that reared its head within her view.

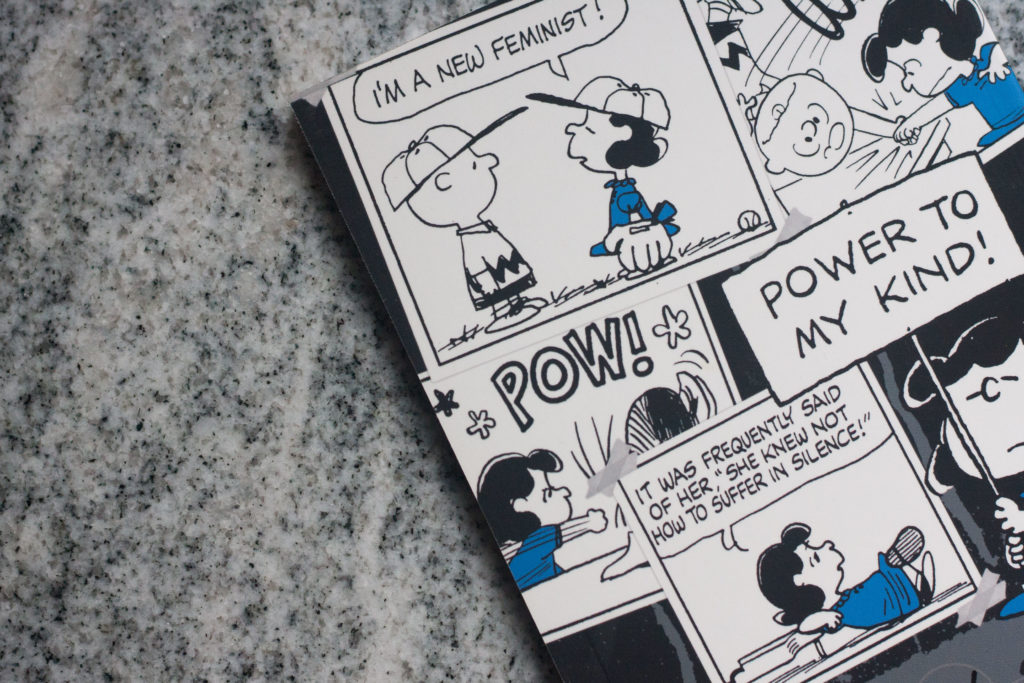

She had choice words for the advice columns that urged young women to fawn and scrape over their husbands (“Just so long as a man isn’t quite as sure as if he knew for certain, whether nothing on earth could ever disturb your affection for him, he is your humble servant…”), walked out in public wearing her husband’s suit to protest another woman’s arrest for wearing men’s clothing, and railed against the stigma that consigned women’s literature to permanent second-tier fluff status. (Little has changed on that latter item, despite Jennifer Weiner’s ongoing desire to poke Jonathan Franzen with a stick).

An 1858 investigative series delved into the life of women at the Blackwell’s Island prison, many of whom were dismissed as prostitutes and unfortunates despite the fact that there were deeper socioeconomic and mental health issues in play; to those readers who might wish to not sully their sunny days with such thoughts, she wrote: “I speak not to you of what was tugging at my heart-strings as I saw them, that beautiful summer afternoon, file in, two by two, to their meals, followed by a man carrying a cowhide in his hand, by way of reminder; all this would not interest you; but when you tell me that these women are not to be named to ears polite, that our sons and our daughters should grow up ignorant of their existence, I stop my ears.”)

The considerable success of Fanny Fern made it inevitable that the (male) establishment would try to ride her coattails, and in a print climate that well pre-dated what we’d consider a modern understanding of intellectual property, Fern ended up in scuffles over her work.

The idea of “exchange printing” was common at the time, with newspapers freely reproducing content from other outlets in order to fill out their pages and take advantage of popular writers or topics. Fern, whose prolific output and pointed humor had made her a household name in the antebellum era, was decidedly no fan of male editors stumbling over themselves to all claim they were her star-makers. Neither did she like the fact that the American press was rather too full of imitators and hack jobs, with editors “reprinting her articles under the name of another writer; attributing to Fern articles not written by her; and falsely reporting that she was writing articles under other pseudonyms.”*

And when a Philadelphia publisher created and printed “Fanny Fern’s Family Cook Book” without Fern’s consent (and in an affront to her sense of style and grammar, no less), she sued to claim sole ownership of her persona. Fanny Fern was not, she argued, a well upon which any opportunist could draw at will. That her public persona was a fiction did not make it common property. The court, remarkably, agreed with her.

In an 1856 column in the New York Ledger, Fern recapped the trial, clearly pleased with the court’s verdict: “Listen! All you who wear (blue) bonnets, and down on your grateful knees to me, for unfurling the banner of Women’s (scribblers) Rights. Know, henceforth, that Violet Velvet, is as much your name, (for purposes of copyright and other rights,) as Julia Parker, if you choose to make it so.”

Fun Facts:

Even as Fanny Fern delighted in her victory, there were some of the era’s inequities she could not escape or steamroll: the case in question is captioned “Parton v. Fleming,” as Sarah Willis Parton was accompanied to court by her husband James, whose presence was required to file for injunction. In print Fanny Fern was sovereign, but in court she was still subsumed into marriage.

James Parton was Sarah’s third husband: her first had passed away after a period of illness, and when it turned out that her second was a real jerk, she moved out with her young children and divorced him rather than quietly endure. She married James Parton, an editor who had been willing to get himself fired over insisting on printing Sarah’s columns when her own brother (who owned the publication in question) wouldn’t. They seemed to have a warm and mutually respectful marriage – in “A Law More Nice than Just,” Fern’s essay on the women-in-men’s-clothing outrage, they make a flirty laugh out of her cross-dressing afternoon, with “Mr. Fern” gamely giggling through the stroll and reminding her, “you must not take my arm; you are a fellow.”

The fact that the offending work was a cookbook made Fern blind with rage: “Issue a book, and put my name to it! Mine? A man to do such a thing! That’s what I call honest, honorable and chivalric. A Cook Book, too! of all unlikely things I should be supposed to get up. A Cook Book! the stupidest of all stupid notions.” **

Fanny Fern was characteristically blunt on the then-current issue of women’s rights to vote, particularly as to the criticism that women should strive to achieve a “satisfactory” level of personal and social maturity before they could be trusted with such a thing: “As it is a poor rule that won’t work both ways,” wrote Fern, “suppose we determine a man’s fitness for the ballot by the same rule.”

“Men inhabit too many glass-houses for them, at present, to hurl missiles of the sort at their fair neighbors,” she sniffed. “Reform yourselves, gentlemen. You who are so much mightier, and stronger, and more competent, by your own showing, show us, poor weak ‘grown-up children,’ how to behave pretty!”

Additional Reading:

** Fanny Fern, “A Premonitory Squib Before Independence,” Fanny Fern in The New York Ledger, Ed. Kevin McMullen (2018)

Fanny Fern, “Woman’s Qualification to Vote,” The New York Ledger, May 23, 1868

* Melissa J. Homestead, “Every Body Sees the Theft: Fanny Fern and Literary Proprietorship in Antebellum America,” DigitalCommons @ University of Nebraska – Lincoln (2001)