Have a drink with: Carl Hagenbeck

Ask him: But do you sing country ballads?

Like many other people, I spent the first chunk of my home confinement (thanks, coronavirus) plowing through Netflix’s hot documentary series “Tiger King” whilst eating an inordinate number of Girl Scout cookies. And the show is so relentlessly bananapants that it’s hard to believe that it could be a product of anything but the current moment in history. But no! The 19th century animal entertainment landscape also involved a cluster of larger-than-life figures jockeying for notoriety and revenue, and the birth of menageries in Western culture can tell us a lot about private zoos today.

There had certainly been exotic animals in the West going back far earlier, as part of private collections meant to demonstrate the owner’s status and ability. (Think Mike Tyson owning a tiger.) But where at the turn of the 19th century there were an isolated few animals in private hands, during the 1800s the menagerie emerged as a structured public entertainment. At first this was a matter of novelty: OMG COME SEE AN ELEPHANT. But as time went on, zoos had to embrace a sense of place in the world, and replaced brutal colonialism with an idea of moral purpose – the idea of participation in education, science and conservation.

Read on at Slate for my full take on Joe Exotic and his historical counterparts.

Fun Facts:

There are detail similarities, too. Just as Joe Exotic and the Baskins got into it over a trademark dispute, so did Carl Hagenbeck. In 1908 he was involved in a legal dispute with the owners of the Hagenbeck-Wallace circus over the use of his name.

Evidence of elephants in America goes back to the colonial era.

When live animal attractions died – which they inevitably and frequently did – entertainers unsentimentally replaced them. As large museums were coming into being around this time, and as they were all seeking specimens in order to build respectable collections, they benefited from the entertainment industry’s high use of animal performers. The nascent Smithsonian and American Museum of Natural History eagerly competed to acquire bones, hides and other specimens from P.T. Barnum’s shows.

It’s hard to overstate how large the animal trade was in the nineteenth century. In 1883 alone Hagenbeck claimed to have imported sixty-seven elephants from Ceylon. According to author Nigel Rothfels, in twenty years’ trade, Hagenbeck had sold “at least a thousand lions, three to four hundred tigers, six to seven hundred leopards, a thousand bears of different varieties (at one time he had forty-two at the same time), and around eight hundred hyenas. Some three hundred elephants had passed through his hands.”

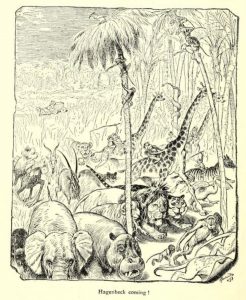

No wonder an engraved plate in Hagenbeck’s autobiography shows a panicky stampede of giraffes, big cats, monkeys and hippopotamus, with the caption: “Hagenbeck coming!”

Additional Reading:

Carl Hagenbeck, Beasts and Men, being Carl Hagenbeck’s experiences for half a century among wild animals (1912)

Nigel Rothfels, Savages and Beasts (2002)

On the Tierpark Hagenbeck, see: “Visit the Zoo Day,” Smithsonian Unbound