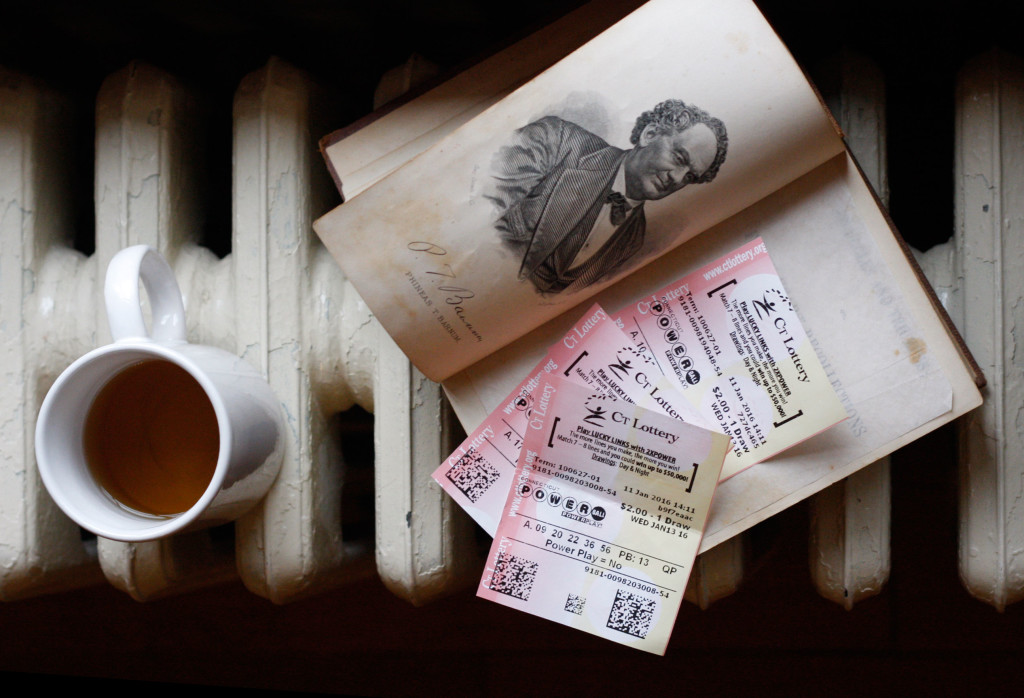

Have a drink with: P.T. Barnum

Ask him to bring Jumbo. That elephant could drink.

Ask him about: Picking your Powerball numbers

Last week I gave in to the siren song of Powerball and joined millions of other people in the giddy exercise of mentally spending the billion-plus dollars of my inevitable destiny (what would it cost for the local museum to let me ride the Brontosaurus skeleton, anyway?).

The unprecedented size of the recent jackpot may have created a real and novel sense of reward, but it doesn’t change the most fundamental truth about the lottery, which has remained unchanged over centuries: the real money isn’t in winning the lottery so much as it is in running it.

In colonial America, lotteries were offered to support all manner of public and private causes, essentially operating as an early form of crowdfunding for the lottery sponsor. That these lotteries existed for a combination of fundraising and entertainment, and that they were structured at the whim of their backers, made them ripe for manipulation and fraud. Still, they were both common and popular; the Jamestown colony in Virginia was famously funded by lottery proceeds, as were many of America’s earliest elite universities.

Few people knew the lottery as well as America’s patron saint of promotion, P.T. Barnum. While plainly unsuited to the family’s farm work in his Connecticut hometown, young Barnum was hardworking, math-minded and ingenious, and by his tween years was already foretelling later-life business dexterity by bartering candy and selling cherry rum to soldiers by the roadside.

He also sold lottery tickets. As a teenaged general store clerk, Barnum sold tickets at a standard fifteen percent commission, and occasionally promoted his own lotteries, gleefully awarding cash-equivalent prizes of surplus glassware he had lying about the place. But he soon realized that all the public infatuation with winnings was so much misdirection; buyers had no idea how the lottery was structured, nor how much profit actually went to the managers and agents who administered the game.

Armed with this insight and eager to profit, Barnum built a network of agents to sell tickets throughout the state. In his 1854 autobiography Barnum notes that he readily sold “from five hundred to two thousand dollars’ worth of tickets per day,” and, ever media-savvy, promoted himself as the “lucky office” to anyone hoping for a winning ticket. Surely this sounds familiar to modern ears.

By the time of that autobiography Barnum was in his forties, and even as it amused him to look back on his young success, he admitted to being “continually annoyed” by lottery schemes foisted on the public, and went on to methodically explain every conceit of the game. Not only was the total ticket pool mathematically defined, managers took a fifteen percent commission off the prize pool before payout, and sales agents sold tickets for twenty-five to thirty percent over their wholesale “scheme price.” An overjoyed ticket buyer might celebrate a thousand-dollar prize, unaware that lottery administrators were aggregating profits in the millions over time.

Barnum clucked at the fundamental opacity of the lottery, declaring: “Thousands of persons are at this day squandering in lottery tickets and lottery policies the money which their families need. If this exposé shall have the effect of curing their ruinous infatuation, I, for one, shall not be sorry.”

Echoing Barnum’s distaste, most states banned lotteries by the mid-19th century, and lotteries as we now know them didn’t appear in the United States until they re-emerged under government monopoly, beginning in 1963 in New Hampshire. The modern lottery is the highest-volume, highest-contact commercial interaction between a given state and its citizens, and the rough math has not changed much since Barnum’s era: for every dollar spent on a ticket, about half makes it to the kitty, with the state taking what’s left after administrative costs, and claiming income tax on the prize.

Estimates suggest that the after-tax lump payout in last week’s $1.6 billion jackpot will land around the half-billion dollar mark, which even split between three winners sounds expansive until you realize ticket sales had to generate in excess of $3 billion to create that prize, a majority percentage of which is going somewhere else. At least in our day that “somewhere else” includes state budgeting by which lottery funds often provide support for line items like public education. In Barnum’s day it was possible that the organizers would just skip town with the whole lot, as happened in the 19th century when Congress tried to bankroll a D.C. beautification project by lottery.

In the end, neither Barnum’s distaste nor any other caused harm to the institution of the lottery, which is as popular as ever, since dreams of transformative wealth sell well in any era, even at a premium. “People would gamble in lotteries,” wrote Barnum, “for the benefit of a church in which to preach against gambling.”

Fun Facts:

While Barnum was a temperance advocate, Jumbo the elephant really did like to drink now and again, allegedly sharing a nightcap with his trainer. The massive elephant was one of Barnum’s most famous attractions, and gave his name for our modern description of oversized Slurpees.

If you ask a dozen people on the street what they know about P.T. Barnum, chances are ten will mention the circus, or tell you that he was a lying liar who lied to people. WRONG WRONG WRONG. (About the lying. The circus thing is true, though it was literally his retirement project.) Barnum was not only creative, smart and nimble; he was arguably the first person to really understand and leverage the American mass media, and pretty much created modern marketing culture. Barnum loved a practical joke or a “humbug” dearly, but only insofar as his customers still got entertainment or information value for their money. As his testimony in the spirit photography trials demonstrates, Barnum found outright deception or predatory marketing extremely distasteful.

Barnum had bad luck with fire (well, let’s face it, so did most of the gas-lit era). The American Museum burned along with its successor, and his palatial Iranistan mansion and a circus facility went up in smoke too. Throw in a modern demolition or two, and Barnum’s only surviving building is now the lovely red stone Barnum Museum building in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Following tornado damage in 2010 the museum is in a process of rebuilding and re-envisioning, but you can still visit select collections including Tom Thumb’s carriage and the totally bad-ass Centaur of Tymfi.

He didn’t say there was a sucker born every minute. Promise.

Those three Powerball winners will make out better than most, interestingly enough, as they come from Tennessee, Florida and California – all states in which lottery winnings are exempted from state income tax.

Additional Reading:

You can read Barnum’s autobiography in multiple editions (i.e., Life of P.T. Barnum and Struggles and Triumphs). He wrote throughout his life, and the books sold like hotcakes – second only to the friggin’ Bible at the time.

The Atlantic, The Economics of the Lottery Ticket

Forbes asks: can you game the lottery?