Have a drink with: Spirit Photographers

Ray? When someone asks you if you’re a god, you say yes.

Ask them about: Selfies with your dead relatives

In 1848, two sisters from Hydesville, New York spread word that they heard mysterious rapping noises on the walls and furniture of their home, and could speak with spirits through tapped code. An enthralled public declared the girls spirit mediums, and over the years household seances, lectures, even Spiritualist “churches” formed a movement – one that survived and grew even after one of the Fox sisters admitted that their spiritual “conversations” were total fluff, the noises no more than dropped apples and cracking their toes under the table.

Just in time for Halloween I’ve been reading David Jaher’s new book The Witch of Lime Street, a detailed romp through the spiritualist revival of the 1920’s, starring Arthur Conan Doyle, Harry Houdini and a real-life parade of mediums, journalists and hucksters. Jaher talks about the movement’s surge in the post-WWI years, due in no small part to the inescapable impact of war and influenza on the populations of the Western world. With so many suddenly dead from violence or virus, the grieving were understandably receptive to the idea that they might contact their friends and family in the hereafter. Would the spirits speak to you? Could they?

That’s all well and good, but Jaher ignores a more pressing question: would they hold still for a selfie?

The 19th century Boston photographer William Mumler is the man today most associated with spirit photography, famous for portraits in which ghostly figures appear to hover around the sitter – images which many took as clear proof that spiritualism was true religion. Mumler claimed to have stumbled upon spirit photography while working as an engraver, when he noticed an unexpected human form suddenly appear on an image plate – and, as author Martyn Jolly notes, “what may, perhaps, have initially been an accidental double exposure and an innocent over-interpretation, quickly became Mumler’s deliberate profession.”

From the Victorian era on, the promise of ethereal guests was titillating party fare, and social gatherings often featured ouija boards, attempted seances, or alleged mediums emanating spectral “ectoplasm” from all manner of places (the many described mediums who secreted the stuff vaginally were presumably very popular at parties).

Mumler went gangbusters with this eager audience, delighting spiritualists with ghostly portraits and carte-de-visite souvenirs that professed to prove, definitively, the existence of spirits among us. (For a fee, naturally.)

The New York police were less enamored – particularly after someone recognized one of the photographed “ghosts” as a man then very much alive – and eventually brought fraud charges against Mumler. The ensuing trial was such a sensation that the New York Daily Tribune reported regularly from the packed courtroom, headlining “Spiritualism In Court.” No less than P.T. Barnum was called as a witness.

Today we think of a photograph as inherently true, an accurate means of capturing a moment in time – but at the same time, we are both aware of and vulnerable to its ability to lie: Photoshop skinnying of models, composite celebrity images, the use of context in journalism. A photo is true, reliable, a known quantity: except when it isn’t.

The earliest audiences for photography were caught in the same back-and-forth. Some felt that technology could not lie, and that a spirit photograph was prima facie proof of the paranormal; others insisted that while a photograph purported to capture an instance of truth, it was inherently subject to manipulation or the whims of process. To be honest, not many people fully understood the new technology or how it worked; and many felt that a photographer was, rather than being an artist or craftsman, just a glorified button-pusher (it took until 1884 for the Supreme Court to find copyright in photography*).

In the end, the judge found insufficient evidence to rule one way or another, and declined to send Mumler to a grand jury. Despite acquittal, the photographer’s business never quite recovered.

Belief in spirit photography persisted, though: Jaher’s book deals in large part with a contest proposed by Scientific American in the 1920’s to see if paranormal claims held up to the light of reason, and one of the categories for which they put up prize money was spirit photography.

No surprise, either; the post-Civil War era saw a boom in innovation, bringing seemingly magical processes like the x-ray, Marconi’s wireless and the consumer camera to market all in a relatively short stretch of time. So spiritualists didn’t feel they were all that far off in trying to approach the afterlife earnestly, even scientifically – after all, you couldn’t see radio waves but could hear the show; so why not believe you might be able to take a picture of a ghost?

No mind that the ghosts often looked like blurs of light, bundles of gauze, or even, in the case of Mina Crandon (aka Margery, the “witch” of the book’s title, exposed by contest judge Harry Houdini as a trickster and sleight-of-hand artist), a gelatinous hand reaching from her nether regions.

Margery, like many other mediums of the day, insisted on being photographed only at the precise moment when her spirits agreed, and in a mix of red lamps, darkness and flashlight. So the camera did faithfully show what was happening in darkened séance rooms – poor lighting, the tracks and blurs of slow-exposure shots, ectoplasm that looked a lot like gauze, and in Margery’s case, a “hand” made out of butcher’s scraps and concealed in those very same nether regions. (Really.)

In the end, spirit photography is less about ghosts than it is about credibility: do you believe in the ghost because it appears in a photograph, or do you believe in the photograph because it produces the ghost you know to be true?

Fun Facts:

American history has litigated the existence of ghosts on more than one occasion. In 1917, a Missouri writer named Emily Grant Hutchings claimed to have used her ouija board to channel Mark Twain from the afterlife, and take spiritual dictation of his new novel, called Jap Herron. The New York Times soon reported on a lawsuit over the book’s paternity:

“On the face of it the suit of Harper & Brothers vs. Mitchell Kennerley, publisher, involves a bald question of property right: but by indirection it involves also the questions whether spirit communication with the living is demonstrable, and whether there is a life hereafter. The riddle of the universe is about to be debated, not by theologians, but by lawyers.”

The Jap Herron case never went to trial. Nobody wanted to spend time and money on a lawsuit, and the book was largely withdrawn from distribution – probably a good thing, since its New York Times book review noted that “[i]f this is the best that “Mark Twain” can do by reaching across the barrier, the army of admirers that his works have won for him will all hope that he will hereafter respect that boundary.”

* In re: copyright in photographs: Hot off an American lecture tour, Oscar Wilde posed for New York celebrity photographer Napoleon Sarony. When one of the photos was taken up by a city department store as an advertisement, Sarony sued, accusing the store’s printer of infringing copyright by printing some 85,000 copies of the image. On appeal to the Supreme Court in 1884, the printer argued that photographs were ineligible for copyright protection, because they were mere reproductions of nature, created by the operator of a machine. Rejecting this argument, the Supreme Court first extended copyright protection to photographs, declaring them original works of art into which the photographer inserts agency and discretion. See: Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53 (1884)

The New York Tribune, April 29, 1869, from P.T. Barnum’s testimony:

“Q: Have you never presented to the public, matters you knew to be untrue, and taken money for the exhibition of spurious curiosities.

A: I think I may have given a little drapery with it sometimes. [Laughter]”

The South Park take on spiritualism.

As Jaher describes, Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was one of the most vocal and prominent advocates for spiritualism, deeply confident that death was but a passage to a different realm, and that a qualified medium could get anyone in touch with their loved ones across time and space.

The issue is still debated today as forms of “spirit photography” are claimed to exist – for example, the late Wayne Dyer and other New Agers were known to talk about “orbs” in modern images.

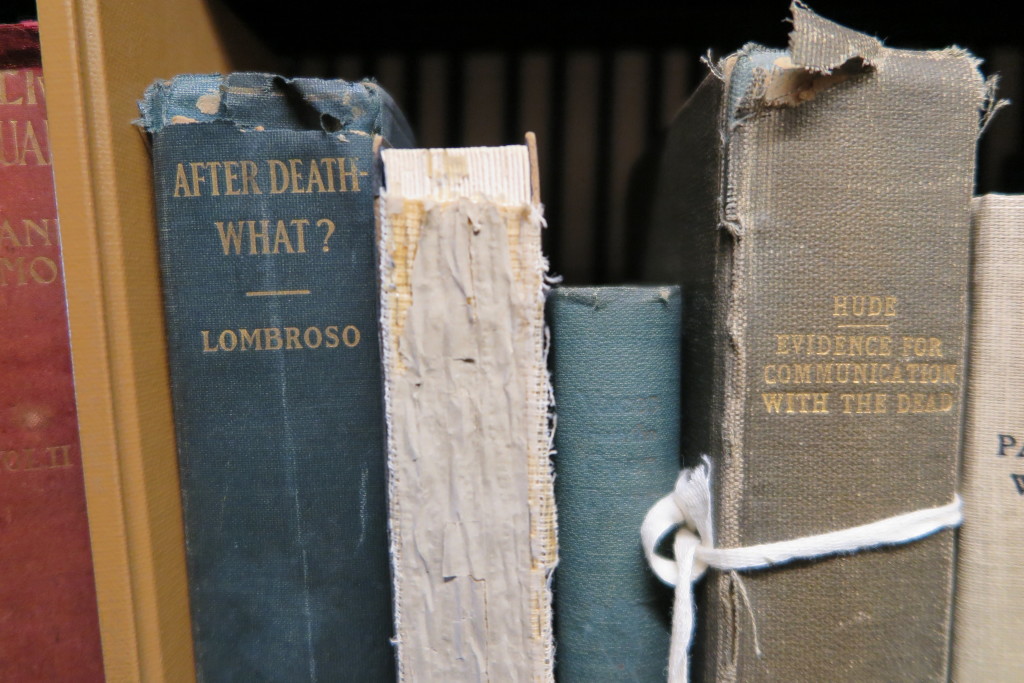

Additional Reading:

The Witch of Lime Street, David Jaher

Faces of the Living Dead, Martyn Jolly

The Case for Spirit Photography, Arthur Conan Doyle

Showtime’s Penny Dreadful (which I love!) depicts a Victorian seance in its first season.

Fascinating article on the history of photography as credible legal evidence, with some in-depth treatment of William Mumler.

Spiritualism is hot this week – Happy Halloween! See, e.g., the Getty blog and Atlas Obscura.