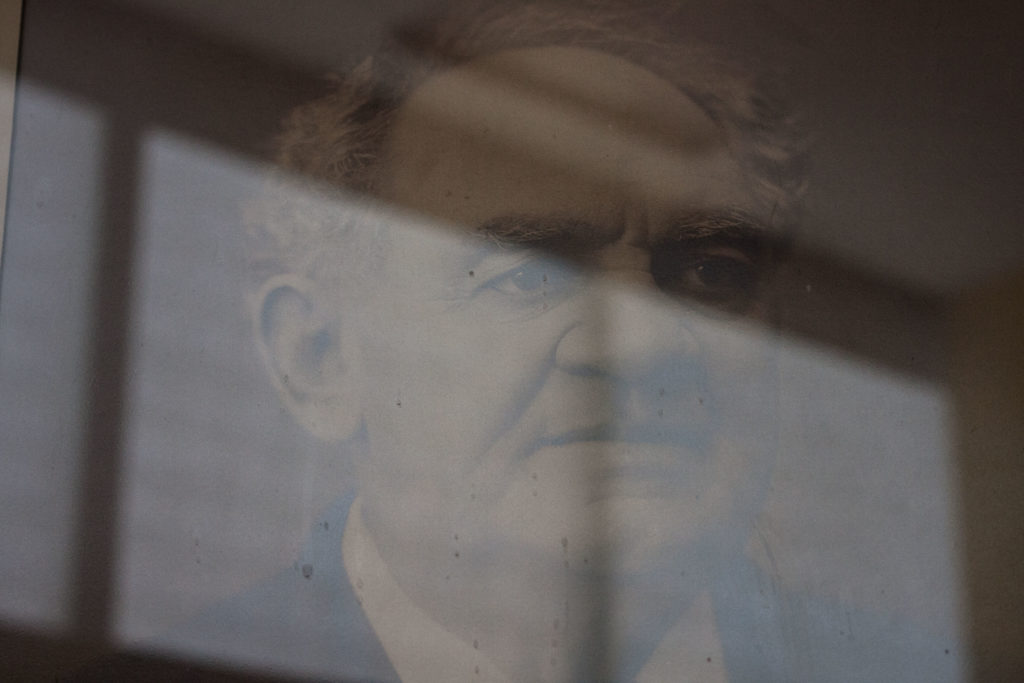

Have a drink with: P.T. Barnum

The Greatest Showman on Earth

Ask him about: elephant agriculture

Barnum month continues! With the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey circus performing its last shows yesterday in New York, and first-look pictures of Hugh Jackman’s Barnum musical The Greatest Showman breaking this week, it’s a good day to tip the top hat to Phineas T.

Here are ten things you may not have known about Barnum:

1. He never said “There’s a sucker born every minute.” P.T. Barnum never spoke his most famous words. In the late 1860’s, workers near Syracuse, New York dug up a ten-foot stone colossus, claiming it was archaeological evidence of Biblical giants having lived in the northeast United States. Really the “Cardiff Giant” was a hoax planted by skeptic George Hull, and as it drew thousands of people to see it, the statue made its owners money hand over fist. When the statue’s owners refused to sell to Barnum, the showman simply created his own “Giant,” and claimed the other guys were showing a fake. One version of the tale has angry owner David Hannum spitting out the famous phrase in the resulting legal dispute.

2. He brought the public aquarium to New York. Barnum’s American Museums were the most popular entertainment destinations in 19th century New York. For a twenty-five cent admission price, visitors had access to five floors of arts, artifacts, animals, human curiosities, concessions and live theater. In an age before zoos, exotic animals were among the museum’s most popular attractions, and Barnum obliged with a menagerie that included live beluga whales. After a particularly unfortunate false start in which the basement whale tank was fatally filled with fresh water, Barnum arranged for saltwater to be pumped into the museum from New York harbor.

3. Ice water, please. The photo of Hugh Jackman and Zac Efron clanging down shots? Not so much. Barnum had been an eager drinker in his young days, but after hearing a temperance lecture railing against the evils of even moderate drinking, he gave up the sauce. Pouring out the contents of his wine cellar, Barnum didn’t turn back, and for the rest of his life was an enthusiastic social and political temperance advocate. His “moral theater” at the American Museum routinely ran anti-alcohol plays – one of which, The Drunkard, was the first in New York City to run for a hundred performances.

4. Thank him(?) for celebrity politics. Barnum was a New York-based entertainer and entrepreneur who didn’t drink, married a foreign-born second wife, wrote a book on “The Art Of” making money, and parlayed his fame into a career in politics. Remind you of anyone? Don’t worry, though: Barnum at least had some morals. A dedicated Universalist Christian and temperance advocate, his motto was “Love God and Be Merry,” and for all his stretching the truth he prided himself on presenting family-friendly entertainment. Barnum served in the Connecticut state legislature and as mayor of Bridgeport, notably delivering a May 1865 speech in support of black voting rights.

5. Got hot summer concert plans? Barnum made a musical and cultural sensation of singer Jenny Lind, “the Swedish Nightingale,” whom he paid an unprecedented $1,000 a night (close to $30,000 in modern money) to tour America in the early 1850’s. Lind was then unknown in the United States, but thanks to Barnum’s promotion the singer – lauded for her wholesomeness as well as her operatic voice – became the height of fashion and admiration. As much as it’s often suggested, the idea that Barnum and Jenny had the hots for each other is a myth, not least because Lind was incredibly proper, bordering on prudish, and flatly rejected suitors including Hans Christian Andersen, who supposedly wrote The Ugly Duckling in her honor (uh, thanks?). Check out last Thursday’s New York Times for more on Lind.

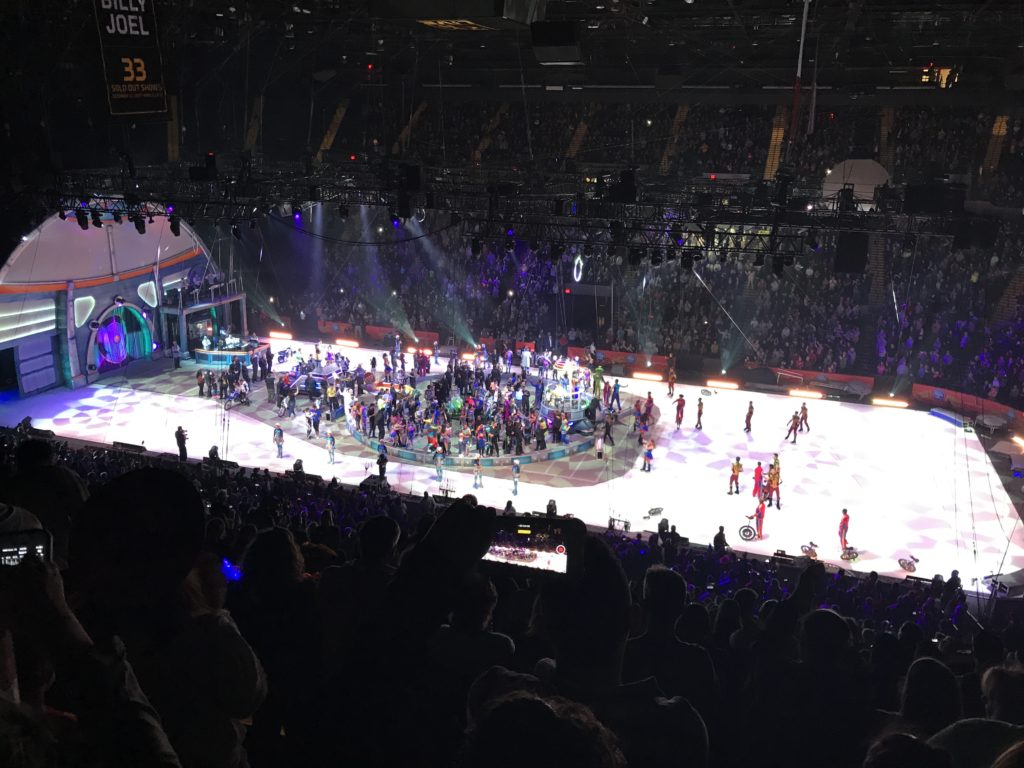

6. The circus was a retirement project. Barnum got into the circus business in his sixties. W.C. Coup approached semi-retired Barnum in 1870 to ask if the showman might be willing to lend his name and profile to a new venture, and so was born “P.T. Barnum’s Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan and Circus.” The show grossed $400,000 in its first year and set Barnum on the path to his famous partnership with James Bailey. Barnum introduced the third ring, put the circus on the growing American railroad, and created the Hippodrome in New York City at the corner of Madison Avenue and 26th Street (which would later become Madison Square Garden). The “Greatest Show on Earth” bore Barnum’s name until yesterday’s final shows.

7. He had crap luck with fire. Barnum’s elegant Iranistan mansion burned down in 1857, both American Museums were lost to fire in the 1860s, the Hippotheatron circus buildings in New York City went up in smoke in 1872, and a 1887 fire took the Bridgeport winter quarters for the circus. The Tufts University museum named for benefactor Barnum, which housed Jumbo the elephant’s remains, burned down in the 1970’s, which really seems like adding insult to injury. Just this year, the movie set for The Greatest Showman, you guessed it: caught fire. It perhaps goes without saying Barnum was eager in his lifetime to invest in firefighting manpower and technology.

8. Alternative facts! Barnum’s first real entry into showmanship was an exploitative 1835 exhibition featuring Joice Heth, an elderly former slave touted as the 161-year-old nursemaid to young George Washington. Controversy surrounded the attraction, and Barnum fed the flames (and repeat ticket sales) by anonymously questioning Heth’s authenticity in the press. When ticket sales flagged, he sent an anonymous letter to the press claiming that Heth was an animatronic figure; when her autopsy confirmed her age at around eighty, news coverage suggested the autopsy itself was a fake and that Joice was alive and well in Connecticut. Though Barnum begged good faith in presenting the show, as he came to abolitionism later in life he was clearly embarrassed by the affair, calling it “the least deserving of all my efforts in the show line.”

9. He hosted Hoboken, New Jersey’s only buffalo stampede. In 1843 Barnum advertised a free-admission “Buffalo Hunt” in Hoboken, New Jersey, drawing more than 20,000 people to see a herd of buffalo majestically race around rodeo cowboys in Native American dress. The crowds were surprised to find that the grand herd was actually fifteen scraggly buffalo calves, were more surprised when their laughter caused the calves to stampede into a portion of the bleachers, and would have been still more surprised to find that Barnum would have considered it a success no matter what happened, since he’d chartered all the day’s ferry boats.

10. He pioneered elephant agriculture. Barnum employed an elephant at his Bridgeport home to periodically plow the fields, hitched to an attendant who dressed in exotic costume and kept the rail timetable in his pocket. Trains regularly passed, and people inevitably asked: Wait. An elephant? Conductors would inevitably explain that it was the home of Mr. Barnum, and well, if you liked that, you’ll love the Museum once the train arrives in Manhattan… Barnum claims to have received correspondence from agricultural societies asking: are elephants good farm animals? How much do they eat? Where can you get one? Do they get along with cows? Alarmed that someone might actually try elephant farming, he advised: “such an animal would cost from $3,000 to $10,000; in cold weather he could not work at all; in any weather he could not earn even half his living; he would eat up the value of his own head, trunk and body every year; and I begged my correspondents not to do so foolish a thing as to undertake elephant farming.”