Have a drink with: James Marsh

Maybe pass on the coffee, though…

Ask him about: Arsenic and old cases

In case you missed, it, I recently wrote at Atlas Obscura about 19th century efforts to take the threat and mystery out of arsenic poisoning, until then one of the most frequent and stealthy means of getting rid of that one person in your life who really can’t take a friggin’ hint. The development of the Marsh Test in the early 1800s meant that suddenly there was a precise, scientific means of figuring out whether someone had been knocked off with history’s own real-life version of iocane powder. Read on:

Fun Facts:

Taboo’s portrayal of the Marsh test is accurate but anachronistic – the show is set in 1814 and deals with the global commercial, political and military upheaval around the War of 1812, while the chemical test dates to 1836.

John Bodle’s poisoned coffee had been served to the entire family, thanks to the frugal practice of re-brewing the grounds; but for that exact reason the effects were strongest in the first cup, served to grandfather. The rest of the family had a bad day, digestively speaking, but nothing much worse. While acquitted at trial, Bodle later admitted to the crime.

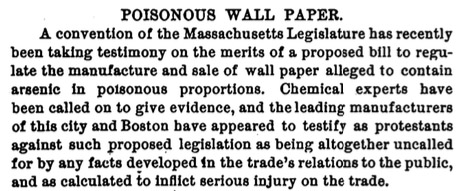

The April 1886 issue of The Decorator and Furnisher Supplement, Devoted to the Upholstery, Carpet, Furniture and House Furnishing Trades – surely a must-have magazine for every household – notes not only concerns about arsenic, but possible Massachusetts state legislation regarding arsenic in wallpaper (a trade representative mentions the Marsh test as an item applied to ensure product safety). Arsenic-free wallpaper was the BPA-free plastic of its time, basically.

And you thought the cough syrup was bad: arsenic was literally everywhere in Victorian England. Green dye was a particular offender: though it was trendy and looked glorious, a ball gown could contain enough arsenic to poison crowds of people (and slough off enough in the course of an evening to definitely kill a dozen). Fashion historians have suggested that Coco Chanel may have been encouraged in her preference for black and white because a superstition persisted by which seamstresses hated green.

Additional Reading:

* James C. Whorton, The Arsenic Century (2010)

David S Caudill, Prefiguring the Arsenic Wars, Distillations (Chemical Heritage Foundation), Spring 2009

John C. Draper, “Precipitation of Arsenic by Heat in Marsh’s Test,” Scientific American, March 23, 1872

José Ramón Bertomeu-Sánchez, “Managing Uncertainty in the Academy and the Courtroom: Normal Arsenic and Nineteenth-Century Toxicology,” Isis, Vol. 104, No. 2 (June 2013)

“Trial of Madame Laffarge,” The Spectator, September 19, 1840