Have a drink with: Dr. James Barry

Poodle enthusiast, dandy, ace physician

Ask them about: trans soldiers

On July 26, President Trump announced a ban on transgender military service, citing the unsubstantiated likelihood that trans soldiers would subject the military to increased medical costs and an unacceptable degree of “disruption.” LGBT rights groups have since filed suit.

For proof that military accomplishment and gender fluidity readily walk hand in hand, we can look to James Barry, a 19th century military surgeon in the British Army who, unbeknownst to nearly everyone in his life, had been born Margaret Ann Bulkeley.

James Barry would have been an impressive doctor in any era. Barry stood out, and not only for his considerable ability: the doctor was a hot-headed army surgeon, prone to dueling and political grandstanding; not to mention that he dressed extravagantly, dyed his hair red, kept a series of poodles (each one of them inexplicably named Psyche) and was a strict vegetarian. As a physician, Barry advocated for the care of marginalized populations including lepers, slaves, women and children; protested against patient care abuses; and researched local plant medicine for treatment of syphilis. In 1826, while serving in South Africa, Barry performed a successful C-section at a time when it was a highly untested and dangerous procedure, saving both mother and child in the process. He eventually rose to the appointment of Inspector General of Hospitals, a senior position in Queen Victoria’s army.

And when James Barry died, folks were shocked to find that the army’s top medical man was, in fact, a woman: Barry was discovered to be outwardly biologically female, with stretch marks consistent with pregnancy.

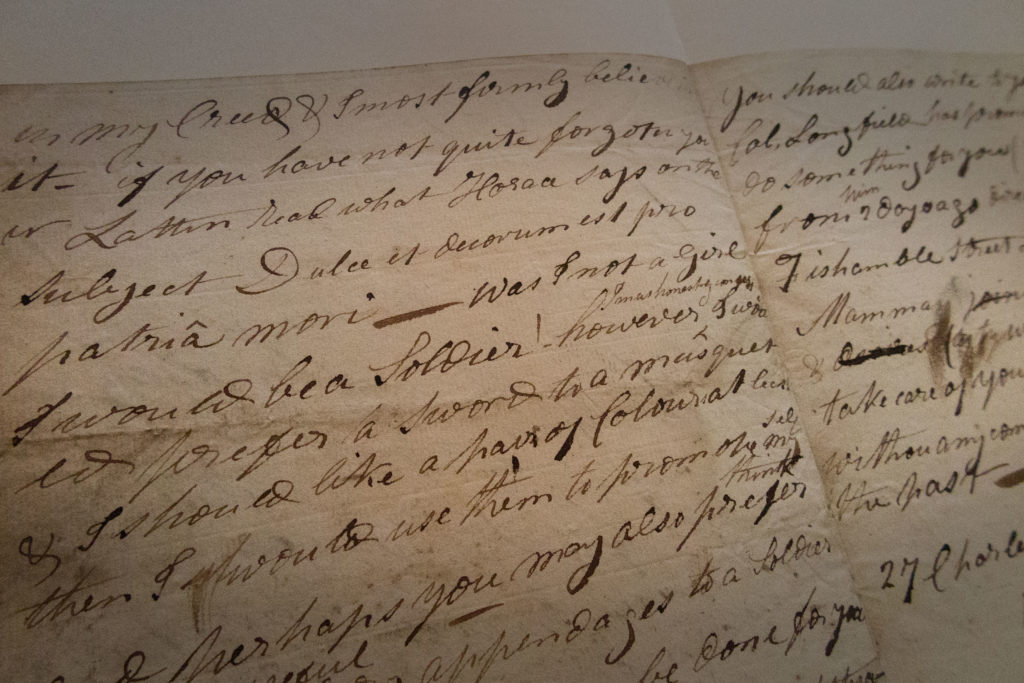

The historical narrative suggests that the girl born as Margaret Bulkeley was guided into medicine by her mother and some helpful family friends as a means of independence and escape from her young life, which was frankly pretty awful. With her father in debtor’s prison, her brother a screwup, and Margaret already a teenage mother due to sexual assault, she was eager to seize the opportunity. Margaret was smart, diligent and fiery; as a girl she once wrote to her brother, who was sniveling about being shipped out in a penal regiment, to shut up and be grateful for his privilege: “Was I not a girl,” she wrote him, “I would be a Soldier!”

Margaret Bulkeley’s life and work as James Barry raise tantalizing, ultimately unanswerable questions. Was Barry gender fluid or transgender before the terminology had evolved to fully, culturally understand those concepts? Was medicine the means to an end – and if so, which end, gender expression or professional success (or both)? Some historians have suggested that, because Barry’s thesis research in medical school focused on femoral hernia – a condition in which one of the pathologies can be undescended testicles – Barry may have been intersex. Others have suggested that the doctor was simply a pragmatic feminist who wanted a career and would discard the restrictions of the era at any cost. Some biographers believe Margaret intended to throw off the disguise after graduating, and move to Venezuela where the revolutionary General Francisco Miranda, a friend of her uncle’s, would encourage her to practice openly as a woman. (If true, this plan went kaput when Miranda was arrested amidst conflict between republicans and royalists.)

The infuriating truth is that the historical record cannot tell us what James Barry felt or wanted. We can guess, but it’s probably an exercise in projection more than anything else. What is as clear today as it was in the 19th century: gender identity and expression have nothing to do with willingness to serve or ability to do so.

Fun Facts:

Not only did young Margaret tell her brother she’d gladly be a soldier, she clarified her ambition: “However I must honestly confess I would prefer a sword to a musquet & I should like a pair of Colours [a mark of officer’s commission] at least.”

Barry’s identity puts some doubt on the typical statistic by which Elizabeth Blackwell gets formal credit for being the first credentialed female doctor, graduating from an American medical school and eventually being admitted to the English register of physicians.

A version of the story is reportedly currently under development as a movie with Rachel Weisz involved.

Biographers have split on the pregnancy question: some have assumed that it was the result of Barry’s long, close relationship with Lord Somerset, governor of the Cape Colony in South Africa, but more recent, better substantiated scholarship has suggested Margaret became pregnant following adolescent sexual assault, perhaps by an uncle, and her child was effectively raised as a sister.

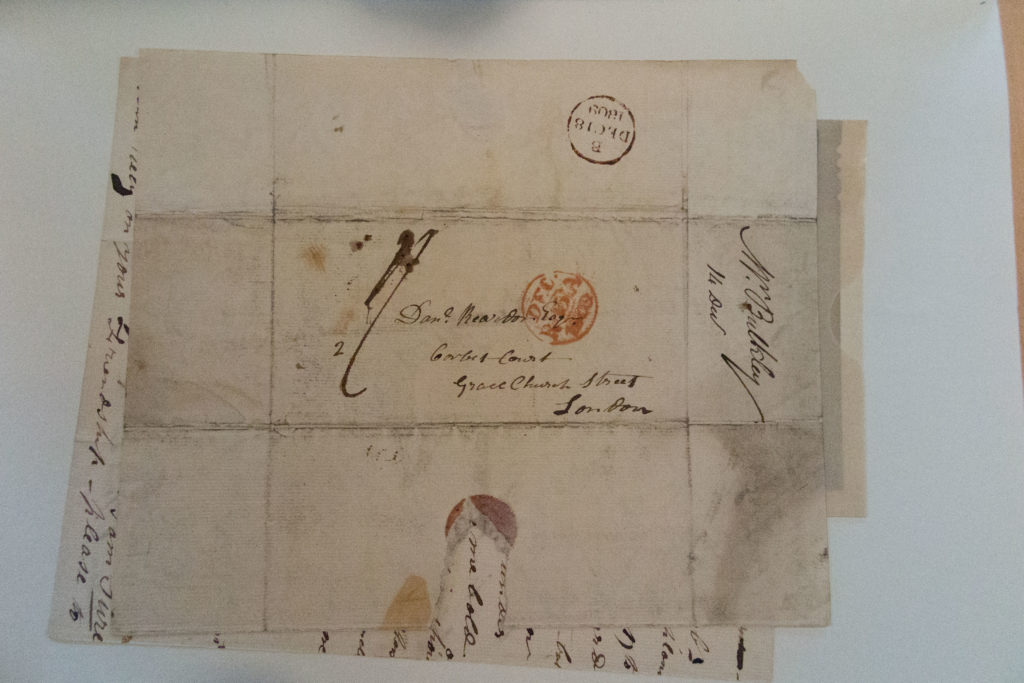

Margaret was guided through education by friends of her uncle, the famous painter (and eventual namesake) James Barry. Margaret’s mother was left on her own thanks to a spendthrift son and a husband in debtor’s prison, and fought tooth and nail against friends, family, creditors and estate law to keep any available assets headed to Margaret’s benefit. Looking at the surviving correspondence she can seem a nag, always reminding someone to send money or update her on sales figures for the Barry art portfolio, which she managed for sale after his death, but remember we only have one side of the correspondence here – and anyway, if you were a single mother trying to get your daughter ahead while escaping a coterie of abusive, entitled broke dudes, you’d be a nag too.

James Barry was no slouch: without the financial safety net available to many well-off medical students of the day, there was only one shot at success and stability. Barry was a bright, hardworking student at Edinburgh, writing home in 1809 to describe study habits familiar to broke college students even today: “…in fact I have my hands full of delightfull business & work from seven OClock in the morning till two the next.”

P.S.: In writing this, I’ve chosen to use the pronouns that Margaret/James preferred to use based on public identity at the time.

Additional Reading:

Michael du Preez and Jeremy Dronfield, Dr. James Barry: A Woman Ahead of Her Time (2016)

Rachel Holmes, Scanty Particulars: The Life of Dr James Barry (2002)

Brian Hurwitz and Ruth Richardson, “General James Barry MD: Putting The Woman In Her Place,” BMJ: British Medical Journal, Vol. 298, No. 6669 (Feb. 4, 1989)

Charles Dickens, “A Mystery Still,” All The Year Round, May 18, 1867 (no. 421)