Have a drink with: James O’Connell & Captain Costentenus

Over 7 million blood-producing punctures!

Ask them about: The many uses of coconut oil

The Greatest Showman, the recent Hugh Jackman movie musical about impresario (and frequent blog subject) P.T. Barnum, centers in large part on the “Oddities,” a troupe of human curiosities Barnum brings from social obscurity to delight crowds at his American Museum. Among these is a tattooed man – and, in this case, fact and fiction align: in the early 19th century, “tattooed person” officially became a career option for white Westerners. Many of them were sailors who, as Robert Bogdan points out in the book Freak Show, “rather than getting a small tattoo on their arm, had their bodies extensively decorated by native tattooers. When they discovered that people would pay to view such skin art, a new type of freak was created.”*

Barnum employed tattooed people in his shows throughout the 1800s, and the movie’s burly, bearded tattoo aficionado looks to be modeled on a real man named Djordgi Konstantinus – Captain Costentenus if you’re nasty.

Nor was Captain Costentenus the first of his kind: the first account of a tattooed Westerner onstage in America is the Irishman James O’Connell in 1840, when he was shown at the American Museum just prior to Barnum’s takeover of the venue. Large-scale tattoos were shocking and unusual in 19th century society, but the thrill of the story was what made them really titillating, and no professional tattooed performer of the era went without a good one.

In a short pamphlet sold to patrons, O’Connell told the tale he claimed had led him to the decorated present: the itinerant child of circus parents, he spent his young life sailing – including on a ship that was transporting no fewer than two hundred female convicts to the Aussie penal colony at Botany Bay. He also spun yarns about whaling, cannibals, shipwreck, and assimilated life among Pacific Islanders, where his story gets to the literal point.

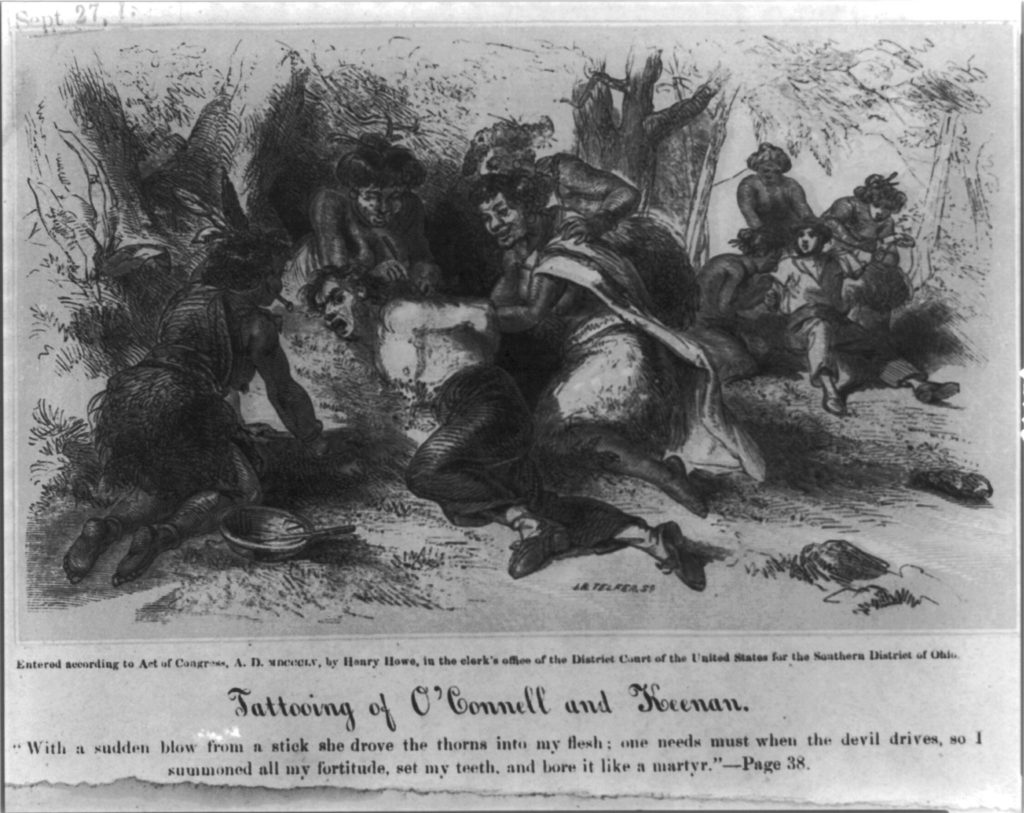

Held quasi-captive in the South Pacific, O’Connell describes being tattooed by a group of ladies armed with bamboo, a “calabash of black liquid” and thorned sticks. Every day they straddle him and tattoo away, and every evening slather him in coconut oil to rest up for the next round. (Hot.) In the end his arms, legs, back and abdomen are tattooed along with one hand – and he is informed that the woman who placed the last few rings and figures upon his skin is now, according to local custom, his wife. After some years among the islanders, he describes escaping to New York in 1835, where he relishes employment in the circus:

“I have nothing further to say, only I am at present in a Circus Company, and from what I have seen in my multifarious wanderings over this wide world, I think this company renders the greatest attraction and variety in the United States, the performers being of the highest order, gentlemanly in their deportment, and praiseworthy in their performance.”**

Is any of this true? We have no idea. Probably not. But it played well, sold even better, and satisfied a clear Victorian-era taste for safely saucy entertainment (forbidden pulp macho travelogue!). The lesson was not lost on Captain Costentenus.

The Captain was a bear of a Greek Albanian man covered in intricate indigo and cinnabar tattoos, with some 388 animal and botanical designs splaying over his eyelids, the insides of his ears, and his scalp. He claimed only a bit of his face, his palms and the soles of his feet were clear.

Performing with Barnum’s Greatest Show on Earth in the late 19th century, Costentenus took O’Connell’s narrative and decided to make Tattooed Man 2: The Tattooing even spicier. The Captain claimed to have been raised in a harem after his town was destroyed by an evil Turkish ruler. By twelve years old he had basically joined the Dread Pirate Roberts, and swashbuckled his way around Asia. He claimed to have for a time passed as a woman named Fatima. Some years on, in a Chinese copper mine, Costentenus was allegedly caught forming an uprising – dragged before a cruel king, he is told he will be punished for his crimes and allowed to choose his sentence: being dismembered, eaten by tigers, stung to death by wasps or tattooed. He chooses the needle and is told: on the off chance you survive, you can go free.

The Captain was a sensation during his employment with P.T. Barnum, who proudly touted the cost of survival: “over 7,000,000 blood producing punctures.” Costentenus was well-known wherever he traveled, since in addition to his body art he wore ostentatious diamond jewelry, smoked fat cigars and braided his dark hair and beard nattily. Doctors were fascinated by him, as were crowds, and he had a certain erotic criminal flair the ladies seemed to love (he would assure them that foreign writing tattooed on his hands labeled him “the greatest rascal and thief in the world”).

Even rascals and thieves have their everyday errands, though. The Chicago Tribune, in 1882, described Captain Costentenus off the stage, on his regular bank visit. The item with some amusement notes the incongruity of the scene: Barnum’s tattooed wonder, bundled in a coat and fur hat, checking in on his finances and exchanging pleasantries with other customers. The correspondents noted with approval that the Captain “has managed to save a good deal more than his salary, and he has invested his money judiciously. The only investment he has that does not pay is diamonds.”

Did that dose of reality deflate his rascally charm? Not necessarily. The article, noting the Captain’s forbidding appearance, considerable gold jewelry (necklaces, twelve rings on each hand and a watch chain studded with twenty-dollar gold pieces) and a colorful silk scarf wrapped about his waist, concluded: “Altogether he looked like a pirate.”

Fun Facts:

The history of the electric tattoo machine is a mix of law, art and science, involving Thomas Edison’s electric pen and New Haven, CT native Samuel O’Reilly’s 1891 patent on a device resembling the modern tattoo gun.

Speaking of the Have, the New Haven Museum recently put up the exhibit Old School Ink: New Haven’s Tattoos to celebrate the city’s history and legacy of body art – at which the Barnum Museum’s poster of Captain Costentenus is proudly displayed.

You’ll note we’re largely talking here about tattooed men. Tattooed women really didn’t show up on the entertainment circuit until the 1880s, for reasons including the socially practical: you have to show skin to show skin, and showing skin was for much of the century still generally considered unusual and lewd for women. Once that door was kicked open, tattooed women were tremendously successful in their own right as performers and tattooers (check out this great photo gallery at the New Yorker on the history of women and tattooing).

The Library of Congress holds a print showing poor James O’Connell suffering his fate:

Captain Costentenus loved his jewelry: the New York Times, describing an 1878 incident in which some toughs tried to rough up Captain Costentenus at a city tavern, noted that the Captain – “a very polite man” – wears “very handsome diamond rings and other jewelry, valued altogether at about $3,000, and usually goes armed to protect himself from persons who might attempt to rob him.”

Captain Costentenus loved his jewelry: the New York Times, describing an 1878 incident in which some toughs tried to rough up Captain Costentenus at a city tavern, noted that the Captain – “a very polite man” – wears “very handsome diamond rings and other jewelry, valued altogether at about $3,000, and usually goes armed to protect himself from persons who might attempt to rob him.”

Additional Reading:

**Life and Adventures of James O’Connell, the Tattooed Man (1845)

*Robert Bogdan, Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit (1990)

Dr. Jane Caplan, “Speaking Scars: Tattoos in the 19th Century,” Brewminate, June 30, 2014

The True Life and Adventures of Captain Costentenus, the Tattooed Greek Prince(1881)