Have a drink with: The Store Detective

Enemy of deviant feminist candy thieves!

Ask her about: hiding a football field’s worth of fabric in your skirt

The modern department store came into its own in the 19th century, as retailers jumped feet-first into the growing Barnumesque sense of spectacle suddenly required to get a consumer’s attention (and their disposable income) in a mass-media society. In an effort to court customers, and to change what it even meant to “need” something, 19th century department stores went all-out in terms of decor and attraction: one Chicago store contained a “reproduction of a gold mine in active operation,” and a New York store had live lizards on hand to add some extra flair to a display, meaning that eventually “the police had to interfere to disperse the crowds.” Other stores offered enticements – free ice cream, a complimentary tea salon, cooking classes.

Much as people joke today about the porn industry being the inevitable first-to-market as far as any technology is concerned, department stores were that innovator in the 19th century. If you wanted to see huge plate glass windows, elevators and escalators, or grand displays of electric lighting, department stores were the place to go – and they were remarkable in that they were specific retail spaces in ways none had been before. Window shopping, for the first time, became a thing.

Stealing also became a thing.

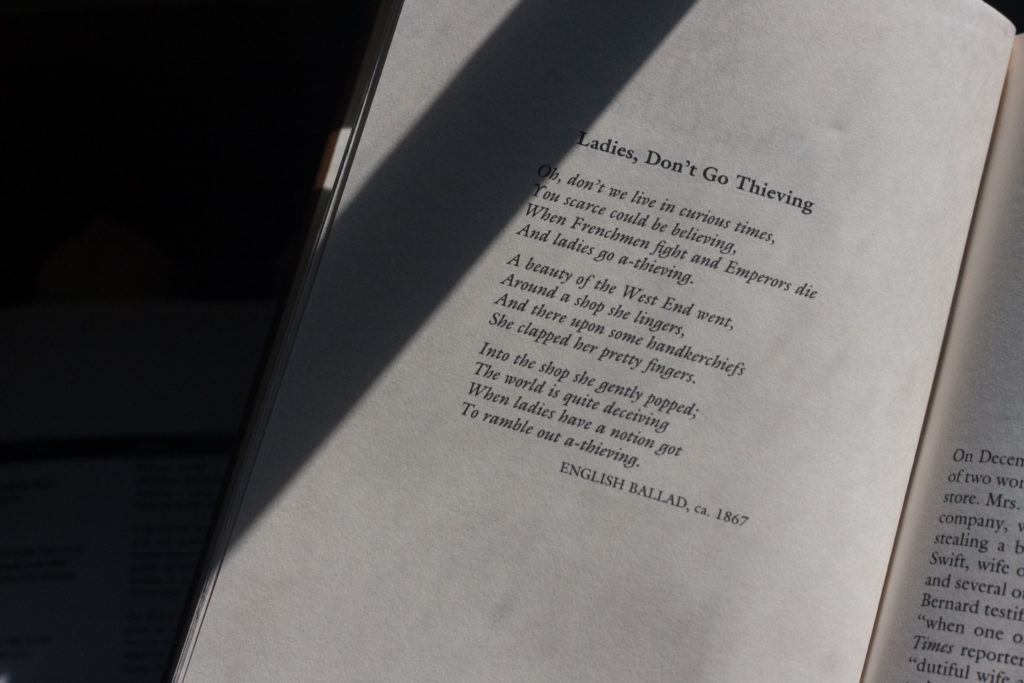

Elaine Abelson’s book When Ladies Go A-Thieving cites one of the earliest such examples from December 1870, when Rowland Macy (of Macy’s fame) arrested Elizabeth Phelps, a “well-known feminist and philanthropist,” for pilfering a small package of candy. Public outrage focused on the store employees who had dared accost a lady, failing to even ask the question of whether she’d actually ganked the Snickers bar.

And, in fact, many of the women who were nabbed for shoplifting in the 19th century were women of surprisingly affluent means, leading to the acceptance of a medical diagnosis of “kleptomania” to explain their actions. Calling it a mania clinicalized shoplifting, and prevented otherwise respectable women from having to be labeled plain thieves. (Lower-class women didn’t have this issue. One store detective scoffed: “Kleptomania? Fudge! That is only a term that is applied to a thief who happens to have social standing.”)

Kleptomania was quickly understood as an inherently female condition, proof of instability and inferiority. One doctor labeled kleptomania as “larceny and eroticism with hysteria,” which sounds like the tagline for a great 1950s B-movie.

Stores started to build in loss margins to their overall planning and inventory. There were consumers who nicked some incidentals, and career shoplifters – including Sarah Johnson and Jane Wise, a team of twenty-somethings who the London Times tells us in June 1864 used the legitimate purchase of a few small items to hide their theft of 120 yards of silk, which they almost got away with under their clothing (and which all but suggests they had to be wearing some really substantial skirts).

On October 5, 1896, Mr. and Mrs. Walter Castle, well-to-do American tourists in London, were arrested for shoplifting, and she in particular became the focus of months of salivating-tabloid news coverage. Though Mr. Castle had been arrested with his wife, he – cast as the long-suffering husband, with no idea his wife’s uterus was such a criminal – was relieved of all responsibility for her theft.

Arthur Conan Doyle, the Sherlock Holmes author, wrote to the London Times on Mrs. Castle’s behalf, claiming that “If there is any doubt of moral responsibility, the benefit of the doubt should certainly be given to one whose sex and position as a visitor among us give her a double claim to our consideration. It is to the consulting room and not to the cell that she should be sent.”

Mrs Castle pleaded guilty and was convicted on seven counts of shoplifting. She was released on her spouse’s promise to take responsibility for her, and they returned to the U.S., where she was taken to Philadelphia for medical examination and surgical treatment. Doctors claimed she could not have had any real idea of what she was doing, and she was “hysterical, weak, and unbalanced, but not criminal.” They conveniently noted that some sort of indeterminate pelvic disease (and by “disease” we mean “existence of female organs,” essentially, since the objective data points to nothing more remarkable than hemorrhoids or irregular menstruation, with a side order of probable postpartum depression) was the likely cause, as it could be responsible in women not only for kleptomania, but for manic behavior, extreme religious fervor and nymphomania too. Any woman whose behavior seemed extreme in any way was understood to be biologically divergent.

Making kleptomania a medical-legal condition generally prevented people from having to confront the plain possibility that women could, perhaps, be devious – that otherwise respectable ladies might have a non-medical motivation to steal. And why might they? In Shoplifting: A Social History, Kerry Segrave notes: “…what was almost never mentioned at the time was that many of these women had little or no money to use with their own discretion. They were wealthy by virtue of the status, position, and occupation of their husbands or fathers.” Even when they went shopping, women were often expected to stick to the list and budget of what they’d been given, and to produce an account. So both rich women and poor were in the same position in a lavish store: all the shiny things in the world, and no ability or latitude to buy them.

Fun Facts:

Diagnosis and judicial treatment arose together in the 19th century, as jurists and doctors confronted the “mad or bad” question; this medical-legal crossover is also where we see the rising prominence of insanity jurisprudence in the 19th century and the use of expert witnesses in court to determine scientific matters of use.

Sometimes, uh, it’s research? Abelson explains: “One young woman, described in the New York Times in 1905 as a ‘literary lady,’ explained that her bag full of assorted stolen merchandise was nothing more than material for a story showing how easy it was to shoplift.”

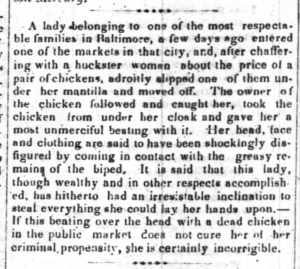

Warning: if you steal something, you could get beaten with a chicken.

Some of the problem here was that consumer culture generally, and department stores specifically, through lavish, multi-sensory displays of “staged luxury,” created an entirely new concept of what it meant to want something; and for women, too, there was a new dimension of social pressure that bore upon them to care what they looked like when they walked outside into the gaze of other people.

Additional Reading:

Most quotes from Elaine S. Abelson, When Ladies Go A-Thieving: Middle Class Shoplifters in the Victorian Department Store (1992)

Kerry Segrave, Shoplifting: A Social History (2001)

Tammy Whitlock, “Gender, Medicine, and Consumer Culture in Victorian England: Creating the Kleptomaniac,” A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Autumn, 1999)

Arthur Conan Doyle was quoted in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of November 10, 1896.