Have a drink with: Oliver Cromwell

He’ll never be the head of a major corporation.

Ask him about: Karaoke hour?

In the last weeks of 1962, if you dug between the photos of miniature poodles and Christmas advertising in your local paper, you may well have read about the solution to a historical mystery: the whereabouts of the severed head of Oliver Cromwell. Under headlines like “Cromwell’s Noggin Found” and “Originator of the GI Haircut,” hometown papers across the United States featured the findings of one Tom Cullen, who claimed to have used “Sherlock Holmes’ own deductive methods” to locate Cromwell’s remains below the chapel of Sidney Sussex College at Cambridge. (In truth, he seems to have called up the university, whose staff matter-of-factly told him that not only had Cromwell’s head been buried in the chapel in 1960, there was a plaque plainly announcing the fact.)

But wait. 1960? What does one do in England for 300 years while dead?

The timeline of Oliver Cromwell’s itinerant head, mirrored in Marc Hartzman’s clever novel, The Embalmed Head of Oliver Cromwell: A Memoir, goes like this: the Roundhead-in-Chief died of natural, albeit unpleasant, causes in 1658 (he very likely had kidney disease). Cromwell’s son Richard lacked the strength to continue in his father’s footsteps, so much so that he earned the mocking nickname “Queen Dick” and was ushered from power in less than a year.

This cleared the way for Charles II’s return to England as king, and just to make sure he got his point across good and proper, Charles had Cromwell exhumed in 1661 for a posthumous execution. Cromwell’s body was hung from the gallows, and his subsequently severed head placed on a pike outside Westminster Hall, alongside some likewise decapitated colleagues, as a warning to anti-royalists. (The body was allegedly buried near the gallows.)

The heads stood for decades as grisly, dried-out cautionary tales (removed but once for some maintenance – on the hall, not the heads) until sometime in the later 1600s, at which time a storm broke the spike on which Cromwell’s head sat, tumbling it from its perch.

The head was taken up by a guardsman who hid it in the chimney at home. Only years later on his deathbed did the guard reveal his odd roommate’s identity, at which point his ostensibly horrified daughter sold the head to Claudius du Puy, proprietor of a museum of curiosities. In the 1720s du Puy conveyed the head to the Russell family, which handed Cromwell down through the generations like a very grisly china set until one particular Russell decided to get rid of the head in partial satisfaction of his not-insignificant debts.

(Enough of the spike remained at the bottom that it served as a convenient handle – so as you read this timeline, do imagine that for centuries, people end up toting Cromwell around like the world’s strangest corn dog.)

From there, the head found itself in the possession of various promoters and showmen, and was eventually acquired by the doctor Josiah Wilkinson, whose family kept it privately into the 20th century, occasionally removing the head from its oak box on a lark to show curious friends and visitors.

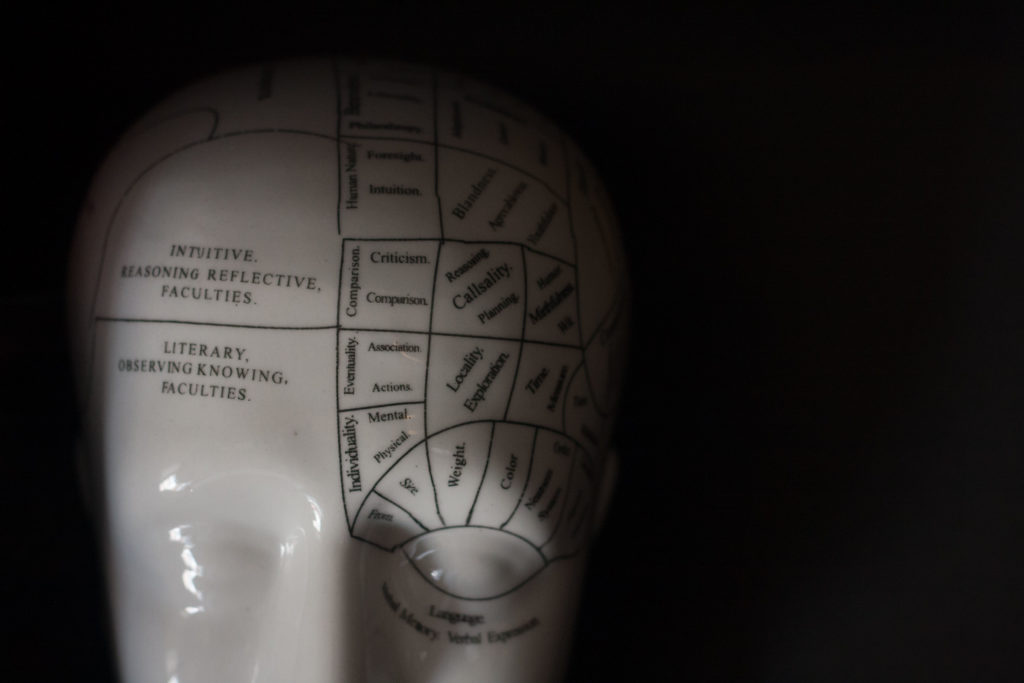

Over the years the family brought in various experts to examine and authenticate the head, among them scientists, archaeologists, numismatists (to compare the likeness with contemporary coins), and even phrenologists. Mr. C. Donovan, in this latter category, cannot contain his excitement as he fawns over Cromwell’s head (endowed by an artist with a laurel wreath to cover the understandably less-than-grand saw marks where the Protector’s brain had been removed for embalming): “That the head of such a man must be an object of the liveliest, the profoundest interest to the phrenologist, will be instantly admitted; – but what phrenologist has ever looked upon that head? Reader, I do verily believe that I have looked upon that head.”

In 1960, the Wilkinsons decided to donate the head to Cromwell’s alma mater, where it was quietly buried below the chapel, its precise location undisclosed to discourage any further shenanigans.

Fun Facts:

No, really: miniature poodles.

A severed head the consistency of beef jerky was hardly out of place in 19th century entertainment culture, which had come to subsist on a constantly escalating sense of spectacle: touting one Colonel Stodare’s display of an allegedly living human head in a box at the Egyptian Hall, a London paper commented in 1865: “Well, heads have been in stranger places for now. On London-bridge, in Temple-bar. Once in a blue cotton handkerchief in an omnibus, once in an iron chest; and Oliver Cromwell’s head has been known to be in at least two museums at once.” Of Stodare’s Jambi-style exhibit, the paper says: “We leave our readers to see the mystery for themselves.”

Phrenology was the supporting beam for all sorts of racist, classist pseudoscience in the 19th century, as well as a floofy amusement for the curious and well-to-do. Phrenology enthusiasts documented the supposedly telltale lumps and bumps of criminals, people of color and the mentally ill to “prove” the biologically-grounded superiority of wealthy white society and its preferred social reform agenda. Orson and Lorenzo Fowler’s New York “phrenological cabinet” was a hot city tourist destination, on the same stretch of lower Manhattan as Mathew Brady’s studio and Barnum’s American Museum. Visitors could look on the busts and skulls of “distinguished and notorious men,” and even sit for their own examination.

The self-justifying classism and utter wackadoo pretension of phrenology is on full display as Donovan praises Cromwell-on-a-stick: “No one,” writes Donovan, “would be justified in saying that this is the head of a fanatic.” Why not? “For there is a perspicacity, a clearness of observation, evinced by the well-formed perceptive region, and a strength of reflection in the upper part of the forehead, under the control and guidance of which it is highly improbably that an educated man, not placed under influences acting almost exclusively on the religious feelings, could pass into a state of general mental action to which the term fanaticism might be correctly applied.”

And hey, if you think Cromwell’s head is weird, that’s only the beginning: you can go visit Jeremy Bentham’s corpse at the Met Breuer through July.

Additional Reading:

Marc Hartzman, The Embalmed Head of Oliver Cromwell: A Memoir (2016)

Frances Larson, Severed: A History of Heads Lost and Heads Found (2014)

Mr. C. Donovan, “On The Reputed Head of Oliver Cromwell,” Phrenological Journal and Magazine of Moral Science, Volume 17 (1844)