Have a drink with: Your Local Phrenologist

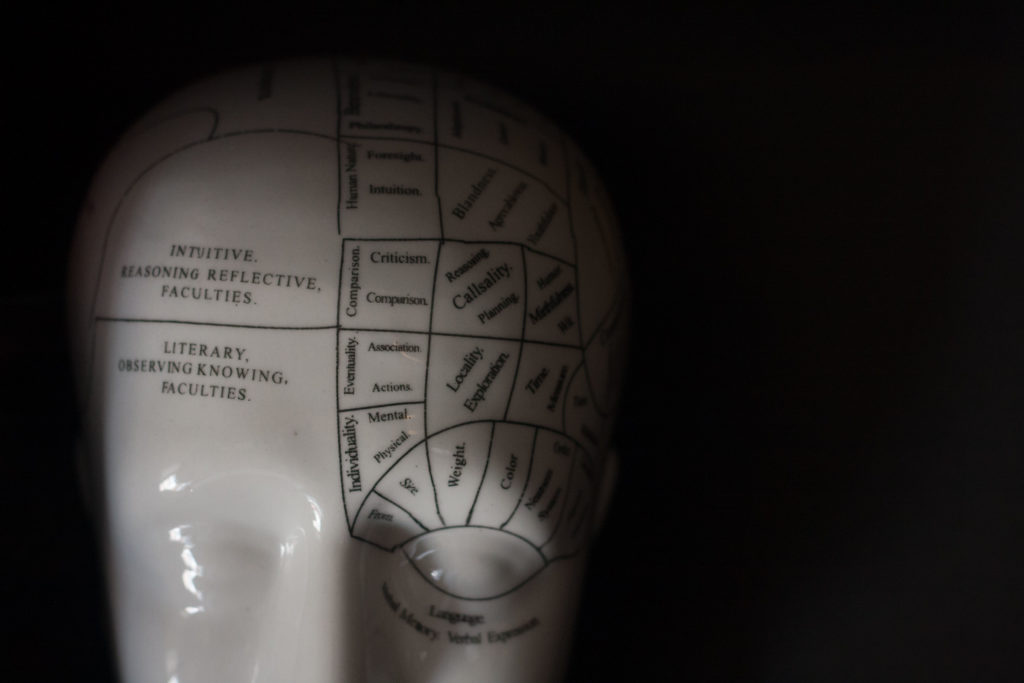

Facial recognition technology is fun: particularly when you can log into your phone as an Animoji lion. But is it reliable, particularly when entrusted with decisions about security – and when profiling is a likely outcome? Suggestions that facial recognition technology can identify bad actors echoes the 19th century belief that phrenology could help identify criminals, and is woven through with the same social anxieties and pseudoscience. I’m over at the Washington Post’s Made by History site today digging into biometrics, phrenology and the problems with using biology to make decisions about criminal guilt, innocence or predisposition.

Fun Facts:

Walt Whitman was a devotee of phrenology, using its descriptive language with characteristic flourish – amativeness, adhesiveness, perceptivity! – and the Fowlers published the 2nd edition of Leaves of Grass.

In New York City the Fowlers set up the American Phrenological institute, a studio and “phrenological cabinet” from which they published phrenological journals, and where visitors could stop to take in the busts and skulls of “distinguished and notorious men,” and even sit for their own examination. Situated on the same high-traffic stretch of lower Manhattan as Mathew Brady’s photo studio and Barnum’s American Museum, it was a popular tourist destination.

Eliza Farnham’s project was interesting, and not just on phrenological grounds. She conceived of her book as an illustrated, annotated American edition of a book on phrenology and criminal justice written by one of the Fowlers’ European correspondents, Marmaduke Sampson (I swear this is his real name). For maximum artistic and educational oomph Farnham engaged daguerreotypist Mathew Brady to take photographs of criminals, from which engraved illustrations would be made. And so Brady, who in the middle 1840s had not yet achieved the fame his Civil War photographs would bring, visited Blackwell’s Island prison and the juvenile facility at the Long Island Farm School, where he produced what may be his first printed work: portraits of men, women and children memorialized as textbook villains.

Additional Reading:

Nicole Rafter, The Criminal Brain: Understanding Biological Theories of Crime (2016)

Marmaduke Sampson & Eliza Farnham, Rationale of crime, and its appropriate treatment : being a treatise on criminal jurisprudence considered in relation to cerebral organization (1846)