Have a drink with: Daylight Saving Time

Spring forward, fall back.

Ask about: How do I change the clock in my car, again?

You may think you have it bad this week, with Daylight Saving Time going into effect: it’s hard to get going in the dark mornings, who knows which clocks you forgot to change, and if the news is to be believed, we get so collectively thrown out of whack by the annual shift in time that there is a nationwide uptick in everything from depression rates to car accidents.

The Sunshine Protection Act, introduced by Senator Marco Rubio in Congress for the second time, aims to get rid of the whole process once and for all by keeping the nation on Daylight Saving Time (which we entered last weekend by turning clocks ahead one hour) year-round. The proposal has been covered in the news extensively this week, with favorable public response.

It’s definitely among the nicer approaches that have historically been taken towards regulating time changes.

In Connecticut, we went ahead and made them criminal.

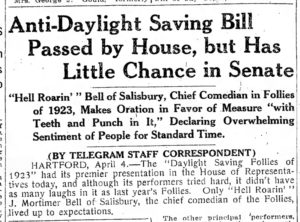

In 1923, largely spurred on by the farm lobby, Connecticut’s state legislature entertained bills that not only required citizens to remain on standard time, but imposed criminal penalties against anyone who was enough of a delinquent to think moving the hands on their clocks was a good idea.

Despite a popular sense that the whole issue was too ludicrous to make it through legislative process (see below), the bill passed and was signed by state Governor Charles Templeton.

The law stated that no person, group or business “shall willfully display in or on any public building or on any street, avenue or public highway any time-measuring instrument or device…any time other than the standard of time as defined by chapter 37 of the public acts of 1921.” Violations drew a $100 penalty.

(This went only for public-facing clocks, so presumably anyone who wanted to feel the hot thrill of rebellion could change their wristwatch or pocket timepiece without real fear of retribution.)

The Hartford Courant, in its coverage, noted that at the moment of the governor’s signature, about half of the clocks on downtown businesses had elected to shift to Daylight Saving Time. The paper, though, assured readers that this was a simple matter of communication and alignment, and no one seemed to have any plans to make a willful protest by continuing to live in the future.

The matter did, however, make it to the Connecticut Supreme Court within a year’s time – one Merton W. Bassett was cited in the case for “willfully displaying on Main street, in Hartford, a clock set and running so as to indicate time other than the standard time as defined by statute.” (Merton, you badass.) The court, remarkably, upheld the clock law as constitutional.

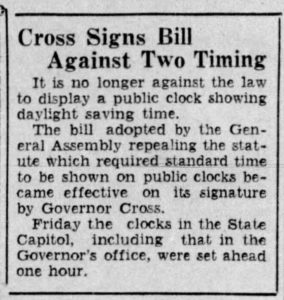

The law was repealed in 1935, and I think we can all agree that the clear winner in this whole story is the Hartford Courant headline writer who announced the end of Connecticut’s experiment with time management:

Fun Facts:

Farmers in Massachusetts, upset when Daylight Saving Time became the law of the land, took their case all the way to the United States Supreme Court. The farm lobby argued against the state’s ability to institute what it considered an arbitrary and harmful time change – making it harder to harvest crops that benefited from morning sunshine to dry out the dew, disrupting schedules of labor and rest, and generally causing “great mental strain.” In support of this argument, plaintiffs claimed that since the federal government had in 1918 passed laws regarding time zones nationwide, time was the province of the federal government and Massachusetts could not interfere. In Massachusetts State Grange v. Benton, the Court affirmed the right of the state of Massachusetts to legislate time.

Connecticut’s governor Charles Templeton was succeeded by his lieutenant governor, Hiram Bingham III (the “discoverer” of Machu Picchu), who held the office for just one day – he had won the governor’s election in November, and in December was elected to the Senate following the death of a sitting Senator. He served a day as governor and then went to Washington.

Daylight Saving Time is not the first instance of American government attempting to make time a less complicated concept for broader society. In the late 19th century, as the American railroad became more widespread and prominent, it became clear that it was extraordinarily difficult to manage clocks and train schedules when every local community set its clocks by the sun at its noontime peak. “Railroad times” being extremely fickle, Scientific American reported in 1883 that rail managers were entertaining the concept of setting four standard time zones for North America, “namely, the time of 60, 75, 90, 105, and 120 degrees west of Greenwich.”* What we understand as modern time zones were standardized with the passage of the 1918 Standard Time Act, which also put Daylight Saving Time into place formally.

The Department of Defense goes into a short discussion of Daylight Saving Time as a wartime conservation effort.

Additional Reading:

Michael Downing, Spring Forward: The Annual Madness of Daylight Saving Time (2009)

James J. Keneally, “An Hour of Light For An Hour of Night,” New England Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 3 (Sep., 2005)

* “Standard Railway Time,” Scientific American, Vol. 49, No. 15 (October 13, 1883)