Have a drink with: Louis Wain

Auteur of psychedelic fractal cats

Ask him about: cat memes

“British cats that do not look and live like Louis Wain cats are ashamed of themselves.” – H.G. Wells

If you love yourself a good cat photo, you can go ahead and thank Louis Wain. Up until the late nineteenth century, it didn’t seem like a celebrity the likes of Grumpy Cat would ever be in the societal cards mostly because no one was all that fond of cats – I mean, sure, people liked to scritch the ears of their barn cats or local strays now and again, or keep a kitten, but for the most part cats’ practical use as rodent control was their standout feature, and they certainly weren’t as friendly or fussed-over as dogs in England. But then Louis Wain decided he was going to draw cats and nothing but cats, and people were HERE FOR IT.

An incredibly prolific commercial illustrator – also the subject of a movie coming out in a few weeks, with Benedict Cumberbatch doing the honors – Wain’s colorful art appeared in books, prints, memorabilia, and newspapers all over England for decades in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Notwithstanding the cheery subject matter, his story is characterized by loss and hardship: Wain was the oldest of six children (most of whom would live with their mother in adulthood, Louis included), prone to frightening dreams and visions, and had been born with a cleft lip. As a result, he did not attend school until the age of ten. Wain grew to adulthood, found art and married in his early twenties (to his sister’s governess, about which no one’s family was thrilled), but could not find stability in relationship either: his wife died only a short few years later of breast cancer. His only consolation during her illness had been to draw pictures of Peter, a black and white kitten the couple had received as a wedding gift, and from Peter emerged an entire career.

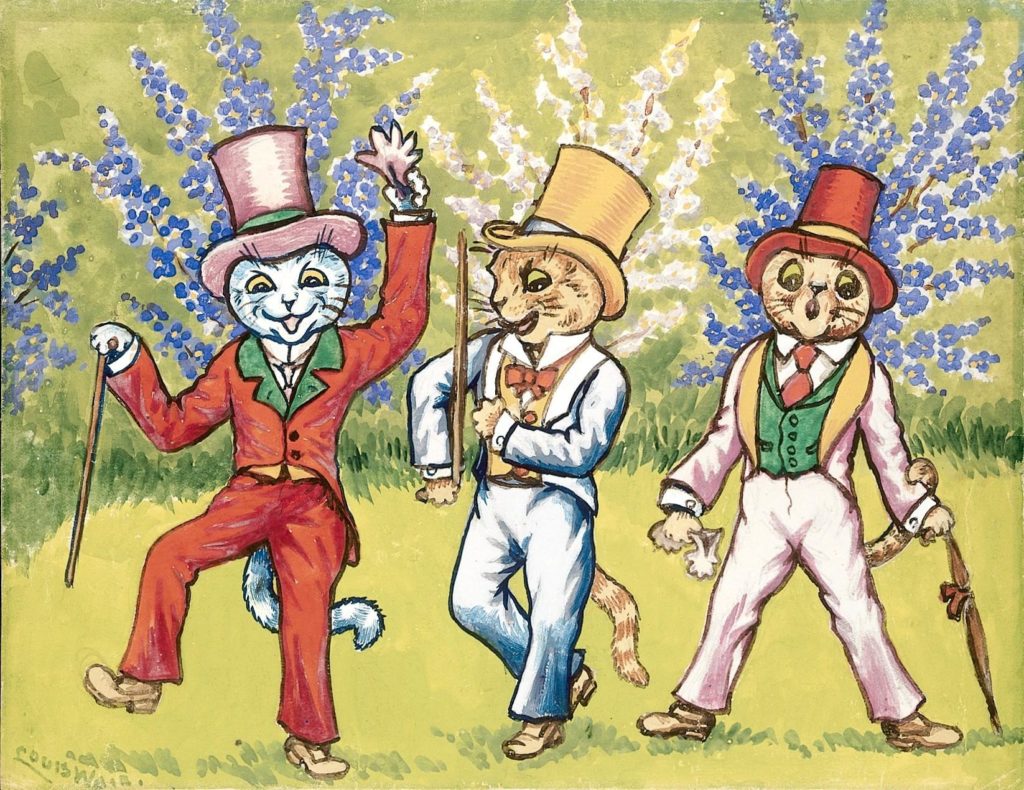

At first they were just cat portraits, but then a style emerged in which Wain’s cats started to walk on two legs and cast their large gleaming eyes on a wide variety of human activities – cats playing golf or cricket, cats dancing or having tea, celebrating Christmas, even. Wain’s vignettes ranged from gentle to plucky to outright funny, and generally steered clear of any sort of menace or conflict. His stock in trade became anthropomorphized cats with giant glittering eyes like Beanie Boos, blithely engaging in English life and threatening nothing worse than the sort of adorable mischief that might look nice on a bedazzled sweatshirt. From the 1880s to the onset of World War I, you could not buy a magazine, read a children’s book or touch something made of paper without a Louis Wain cat staring out at you from it, manic and unblinking. At his height of popularity, Wain drew hundreds of cats a year.

The war soundly whomped the market for his drawings, though, and Wain, who had poor business sense, was undone by failed investments and a failure to retain copyright in most of his work. His mental health challenges became more pronounced, and Wain eventually ended up in the pauper’s ward of the Springfield Mental Hospital.

Unbeknownst to him, though, Wain had his devoted fans. A committee led by War of the Worlds author H.G. Wells sought to raise money to improve his situation, appealing to generations of Britons whose fond memories included children’s books, newspapers and advertisements happily plastered with cats. Wain’s care (and that of his elderly sisters) was crowdfunded to the tune of more than two thousand pounds.

Wain continued to make art even after he entered asylum care, and this is a good point to note that over the years, his art showed a marked shift in artistic tone, which one can only describe in macro-level terms as (1) Realistic Cat Period; (2) Whimsical Cats Doing Human Things; and (3) Cats Tripping Balls.

IMAGES: Wikimedia Commons / Wellcome Collection

IMAGES: Wikimedia Commons / Wellcome Collection

In his own time and among modern historians, folks have speculated that the change in Wain’s art mirrored his own mental health journey, showing the emergence of schizophrenia. But whether there is a direct correlation between his art and mental health is uncertain. Wain didn’t date his works, and artists mature, and retroactive diagnosis is a dodgy sport. Some people think Wain had autism; others, that he was just particularly experimental; still more, that the abstract patterns in his later works are reflective of fabrics in his mother’s house.

Fun Facts:

A 1931 article in the San Francisco Examiner claimed that Wain, normally left-handed, had switched to right-handed cat art while in the asylum and begun to produce “only demon cats with malevolent faces – a strange example of dual personality.”

In 1917, Wain considered taking part in creating an animation short called “Pussyfoot.” The project did not get off the ground (because, with his usual lousy luck, Wain was literally hit by a bus when contracts came due), but given the character’s proposed look and as Wain had done more than nearly any artist to bring humanized animal characters into public entertainment, it’s considered a forerunner to the likes of Felix the Cat and early Walt Disney / Ub Iwerks characters.

Wain believed cats were more trainable than dogs. That’s it. That’s the fact.

Additional Reading:

Victorian Cats, Medieval Hospitals & Frontline Workers (podcast), National Archives (UK), November 26, 2020

Claire Wrathall, “Crazy cats and the tale of a tortured artist,” The Independent, September 17, 2011

Chris Beetles, Louis Wain’s Cats (re-issued 2021)