Have a drink with: The Gordon Rioters

Angry Protestant mob, muse to Charles Dickens

Ask them about: Looting, pillaging, using the word “popery” without laughing. (Try it: popery popery popery.)

“If they touch my work that’s a part of so many laws, what becomes of the laws in general, what becomes of the religion, what becomes of the country!”

You wouldn’t be wrong to wonder if this quote came out of Indiana in recent weeks, or perhaps Arkansas, in the face of debate over whether founding concepts of religious liberty could in fact literally be discussed over pizza. But in fact the quote is from Charles Dickens’ neglected novel Barnaby Rudge, in which a panicky hangman frets over religious freedom laws in 18th century England.

Dickens took his story from the events of June 1780, in which Protestants gathered with Lord George Gordon to march on Parliament and there present a petition for the repeal of Catholic relief legislation. The crowds grew and surged as they moved, and a week of “No Popery” violence broke out in London, requiring some 12,000 troops to restore peace.

To put such an extreme event in context: the average Englishman in the 18th century understood certain things to be true about Catholicism. If stereotypes were to be believed, Catholics were violent idolaters, oddly predisposed to calling upon a pantheon of saints and mothers, and most gravely, part of a giant sleeper cell bent on the papal takeover of Europe.

A sermon preached in Newcastle in 1780 warned parishioners that Catholics would accept no peace with heretics: “[h]owever mild and gentle in Protestant countries Popery may appear to unwary eyes, yet for a moment consider the following steps of intolerance, and you will see them full of danger, and marked with blood.”

Efforts to secure Protestantism began with Queen Elizabeth, whose first legislative action after thirty years of religious flip-flopping was to institute a temporal and spiritual loyalty oath; recall that Henry VIII began his reign as recognized Protector of the Faith but finished it as a monarch in the Church of England, and not soon after Queen Mary I earned the epithet “Bloody Mary” for her staunch and often violent reinstitution of Catholic policies. The oaths and restrictions contained in anti-Catholic legislation offered Elizabeth and subsequent English monarchs a means to solidify and better control government.

The discovery in 1605 of the Gunpowder Plot and its architects’ Catholicism sent king James I a gift-wrapped public relations package – supporting evidence for a true Catholic conspiracy! – and cleared the way for even stricter legislation, which increasingly asked Catholics not simply to swear fealty to the crown, but to denounce articles of their own faith.

By the Restoration era, the “Penal Laws” were at their height: refusal to take the oaths in effect under Charles II meant losing virtually all legal status in the English system, including access to court, inheritance rights, guardianship of children, and official employment. Most Protestants felt the Catholic menace was thereby safely contained.

So when George III decided to pass the Catholic Relief Act of 1778, it didn’t go unnoticed that the law did not require Catholics to denounce their faith, simply to swear temporal loyalty to the king. (George’s oaths do state that it is an “unchristian and impious” position to murder another person for their religion, but who would argue?) Still, many felt the law was a clear and dangerous downturn in the protection traditionally afforded by the state, and the Gordon Riots followed.

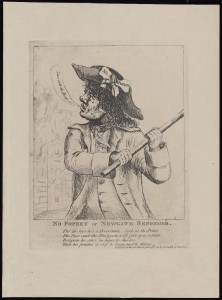

Even from the start, critics wondered if rioters really cared so much about doctrine as the opportunity to loot and pillage. A James Gillray cartoon of the day, entitled “No Popery, or Newgate Reformer,” was captioned with a snappy little rhyme:

“Tho’ He says he’s a Protestant, look at the Print,

The Face and the Bludgeon will give you a hint,

Religion he cries, in hopes to deceive,

While his practice is only to burn and to thieve.”

Even if the mob was less than pious, though, their fear wasn’t manufactured. England under George III was deeply concerned about the stability of the nation: the country was financially stretched after the Seven Years’ War, the American Revolution was in full swing, and no one in power wanted oppressed and impoverished Ireland to get any ideas about independence from the colonies.

It is no stretch to suggest that the typical English citizen perhaps worried that the whole country was headed to ruin, and found in the wax and wane of religious legislation a convenient and comforting hook on which to hang all that anxiety.

And just as an 18th century Protestant Londoner might have worried about the shape of his life in a world of unfettered Catholicism, Christian RFRA proponents today have argued that, without protective legislation, their dearest rights are on shaky ground (this is to say nothing of Catholics and the LGBT community, respectively, who in such environments justifiably offered to introduce pot to kettle).

Dissent played out very differently in the two eras, however. Early modern Catholics were unable to meaningfully object to restrictive laws; even in an age of parliamentary democracy folks still worked more in the spirit of the then-familiar phrase “cuius regio, eius religio” – meaning “whose reign, his religion” – and English anti-Catholic legislation survived into the Victorian era. Indiana, besieged by criticism and boycott, rushed to clarify its freedom legislation inside of a week.

Even for those like me, who grew up with Schoolhouse Rock to assure us that civic process could find its cool, legislation still had a certain heft and rigor; like a heavy truck, you could count on it to take a creaky start, and occasionally to hit the garbage cans a few feet beyond its braking point.

For the most part this is still true; just ask anyone trying to legislate data security or repeal the excise tax. But as lawmaking bears the fast, thorough and continued judgment of all forms of media, we are seeing pockets in which government adopts a climate of accelerating iteration, little swirling eddies in a larger sea. RFRA’s have created one of these.

The maturity of social media has dramatically increased information’s speed and penetration, intensified the emotional climate of disagreement, and made a watchdog of anyone with a smartphone. Further, when it comes to legislating faith and belief the perceived separation between government and public is pressed especially thin. We expect our legislators first and foremost to be public servants, proclaiming that our tax dollars pay their salary and our votes keep them in office, and the public increasingly uses not only our voting rights but our spending habits and online personae to keep that fact sharply front of mind.

Once upon a time, it took centuries to move a matter of religious legislation. Now a week of hashtags does the trick.

Fun facts:

The Penal Laws may be gone, but British royalty STILL can’t marry a Catholic, and there was discussion in the very recent past about whether there could be a Catholic Lord Chancellor.

Check out a cool map used in the Gordon Riots.

Look. No one has read Barnaby Rudge. Not even Dickens. Edgar Allan Poe famously wrote of Dickens’ oft-forgotten novel, “Our author had not sufficiently considered or determined upon any particular plot when he began the story.”

Speaking of Poe, was The Raven stolen? Poe was rumored to have been very fond of the character of Grip, a raven based on one of Charles Dickens’ own pets, and wrote that he had wished that Grip had been more of a prophetic character through the novel.

“Rarnaby Budge?” Monty Python’s Bookshop Sketch.

Additional Reading:

Barnaby Rudge, online and in hard copy.

Courtesy the UK Nat’l Archives: “Reproduced here is part of the charge sheet from Gordon’s trial, plus an advertisement announcing the forthcoming publication of The Thunderer, demanding the release of the rioters (139 were arrested and 21 sentenced to death) and calling for an end to Popish plots.”

Text of the Charles II Test Act.

For modern context vis a vis RFRA’s, see the Atlantic and my genius friend Dan Klau on how CT / IN laws differ.

The Gordon Riots: Politics, Culture and Insurrection in 18th Century Britain.