Have a drink with: Harry Hill

“Take a little wine for thy stomach’s sake.”

Ask him about: How’s your head?

Harry Hill was a British-born horse-racing enthusiast and barman who ran a multi-purpose bar, concert hall, fight venue and gambling house at Houston and Crosby Streets in 19th century lower Manhattan, a scant mile and change uptown from Barnum’s American Museum. Hill was a colorful character whose combination of brawn, acuity and street-smarts gained him broad respect and local notoriety: he entertained a rough crowd but strictly enforced house rules about behavior and relative quietude (no swearing or unsanctioned brawling allowed, and while you’re at it, order a glass of wine for your digestion).

His New York Times obituary, printed August 28, 1896, described Hill as “a queer combination of the lawless, reckless, rough, and the honest man.” This was an understatement: Hill was the type of guy who once had been stabbed with a penknife by a disgruntled female patron, and seemed not to consider this out of the ordinary.

Nelly Smith and Jennie Collins were two prostitutes who frequented Hill’s for drinks and dancing, and as the press told it, Smith was “under the protection of a Cuban, who spends a great deal of money on her, and she frequently gets gloriously drunk.” Hill had tossed the pair out more than once for offenses including rowdiness, spitting and yanking the banjo player’s beard. One night they returned with a friend named Fanny Kelly and their then-current boyfriends (who wisely “kept very quiet” throughout the evening), and when Nelly’s “playful eccentricities” emerged, Hill went once again to kick her out of the bar. Fanny Kelly took that as her cue: rushing in, she attacked Hill with a pen knife, and it wasn’t until she buried the inch-and-a-half blade in his right temple that he realized what was going on. “Hill did not mind the blows on the left temple,” noted news coverage, as “he thought she was merely punching him with her fist; but the third time the knife entered so deep that he knew he was stabbed, and he struck her in the face with his fist and knocked her down stairs.” Hill was ultimately unfazed, and “walked home with the greatest sang froid.”

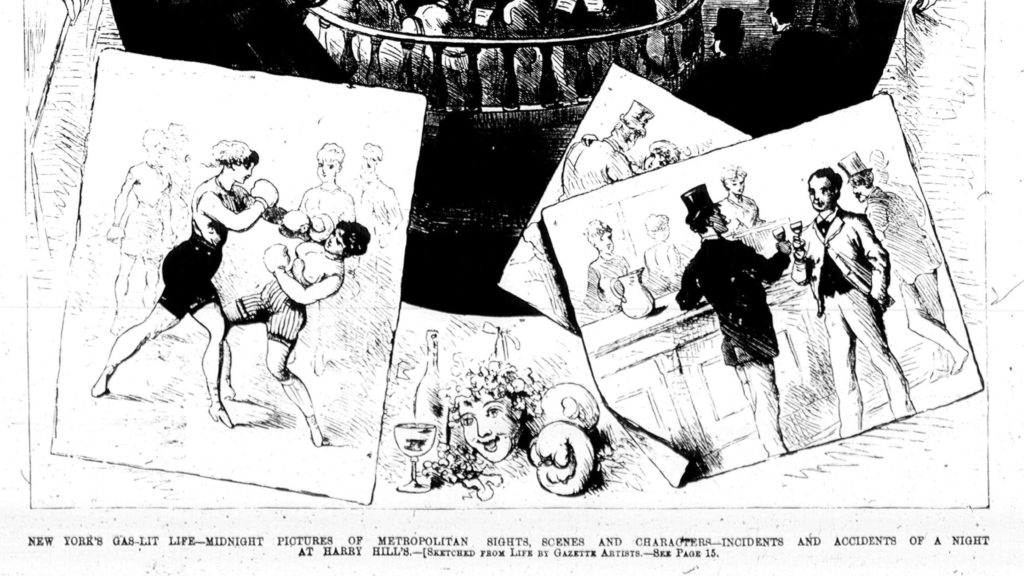

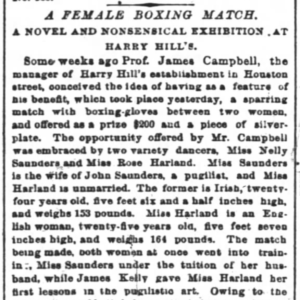

Not only was he cool as a cucumber, Harry Hill had a reputation for being the sort of guy that gangsters could count on not to take sides, and drunks trusted with their gambling money because they knew he’d hand it all back after they’d sobered up. He was like a burly, grumpy Switzerland. And since he had the venue, the clout and the cred, Hill promoted not only dancing and theater, but many of the city’s major prize fights – some of which featured female contenders.

This frequently tagged him with some of the same criticisms that his neighbor P.T. Barnum was used to hearing, about how he was nothing but a cheap, seedy downtown hack who was sending decent culture down the tubes. He didn’t particularly care, not least because he drew a solid crowd: Thomas Edison’s first large-venue electric light system was installed in Hill’s establishment, all the better to see you with; and the wide-ranging clientele included not just Bowery toughs and gangsters but high-society guests like nude-carriage-riding aficionado James Gordon Bennett, Jr. and Oscar Wilde (who to my knowledge never took a nude carriage ride but who I bet would have had something particularly droll to say about the practice).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the New York police were no fans of Hill’s, and frequently visited his venue to try and get him on some charge, anything at all – liquor licensing under the excise law, fight certification, his “waiter girls,” or just plain police graft – and this was as much to pester Hill into forced obsolescence as to actually get a charge to stick, since there was no guarantee of the latter. In October 1886, for example, Hill was dragged into court on the charge that he had staged a boxing match and thereby given a “theatrical exhibition without having a license.” Hill calmly replied to the judge that, the 150 men in his bar being particularly bored that day, two offered to box to break the monotony, and the crowd, well, being decent men they all put up $5 for each of the volunteers for their trouble. Hill’s counsel explained that the fight was merely “an exhibition of athletic exercise,” and that if Hill could be arrested for that, well, every gym owner in New York could be convicted. The New York Times reported that on those words, “Hill was discharged, and left the court room with a smile on his face.”

Fun Facts:

Hill’s wasn’t the only rowdy joint in town. Hill’s obituary in the New York Times includes a story in which a fight promoter named Felix Larkin, upset at losing a racing bet at Hill’s, stomped down to the venue to start a fight. Larkin and his opponent drew their guns in the bar and were arrested. Once discharged from police custody, Larkin went directly to another bar to start a fight, and was killed when the proprietor of that bar stabbed him seven times. With a cheese knife.

An 1881 Philadelphia Times article entitled “Circus Kings in Arms” describes the rivalry between P.T. Barnum and circus promoter Adam Forepaugh, who attacked Barnum precisely by associating him with the likes of Hill: “a prominent feature of the show was a wrestling match, which only lacked a dog fight to make it equal to the show of his neighbor, Harry Hill, on Houston Street, in Murderers’ Row, where Mr. Barnum’s late-lamented tenant, ‘Reddy the Blacksmith,’ formerly resided.” (This was a dig against the fact that Barnum, who always maintained a sizable real estate portfolio, happened to own the lease on a Manhattan property that was used as a saloon by the notorious Bowery criminal William Varley, aka “Reddy the Blacksmith,” a surly ginger with hobbies that included smithing burglary tools, drinking and brass-knuckle brawling. It’s also said that Barnum had an interest in Hill’s building.)

The Police Gazette, originally a crime blotter, became one of the first men’s magazines in the modern Maxim-style mode. After it was purchased and revamped, the magazine – printed on red paper, no less – became one of the prime players in a new realm of sports and lifestyle journalism. The Police Gazette featured coverage about sports, women and tawdry true-crime stories, and sponsored wrestling and boxing events at a time when live fights had both a new whiff of mainstream acceptance and the thrill of illicit activity.

Hill’s spending and investment habits played a role in his eventual decline, though perhaps not so much as police interference. Hill was reported to pay as much as $300 a week – thousands of dollars today – in “protection money,” and in retaliation for complaints Hill had levied about officers blackmailing him, the police secured orders that Hill should close up shop by one in the morning. This was, the papers noted, “tantamount to closing it altogether, as his most profitable business was done between midnight and daylight.”

Additional Reading:

David Favaloro, “Beer and Morality in the 19th Century,” Tenement Museum

Edward van Every, Sins of New York as “exposed” by the Police Gazette (1930)

“‘Arry ‘Ill,” The Daily Commonwealth (Topeka, KS), November 17, 1869

“A Female Boxing Match,” The New York Times, March 17, 1876