Have a drink with: St. Teresa of Avila

Reformer, mystic, dreamer, smart lady.

Ask her about: that time she told the devil to piss off.

I grew up thinking saints were terribly stodgy, righteous people who had somehow gotten themselves onto life’s “Do Not Call” list for doubt and temptation. It wasn’t until later in life, when I learned that hagiography is basically a template for fictionalizing the lives of remarkable yet messy people, that I realized many of them would probably have made excellent drinking buddies.

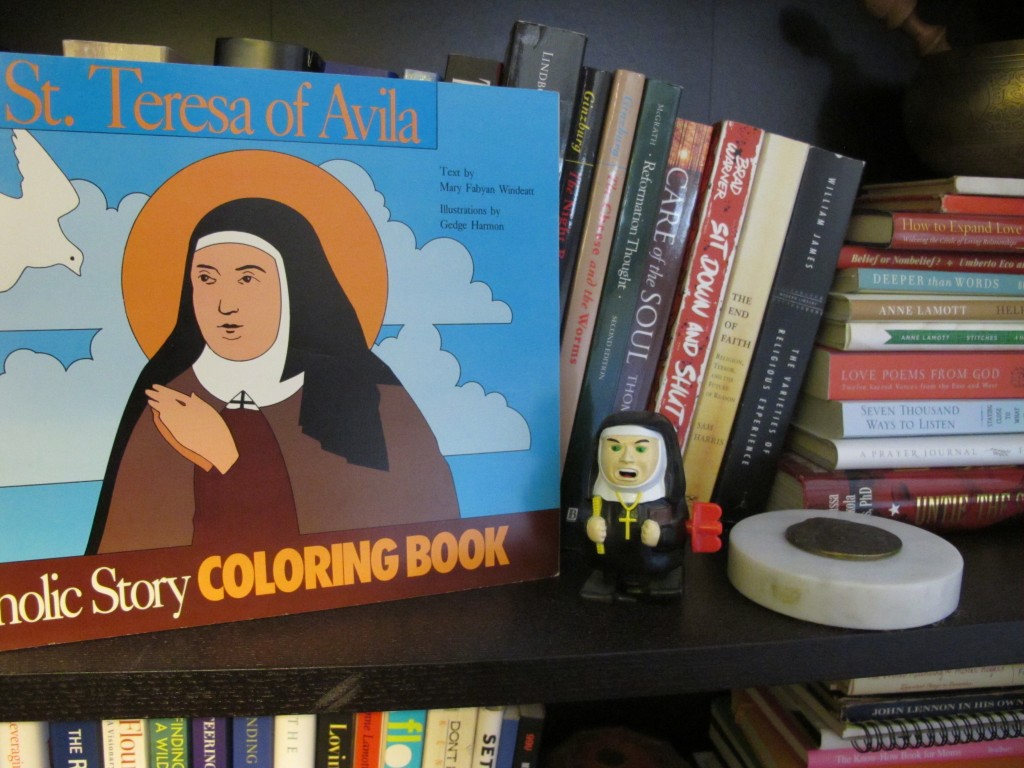

My personal favorite is Saint Teresa of Avila, the first woman doctor of the Catholic Church and a stone-cold sixteenth-century bad-ass. I own a St. Teresa coloring book. You can’t but be awesome if someone made a coloring book about you.

Teresa grew up in sixteenth-century Spain, smack in the middle of what we’d now call the early modern period in Europe and the Spanish (Counter-) Reformation. This is to say: Lots Going On. Europe had suddenly gone pro in hair-splitting points of church doctrine; academic humanism was on the way up; there was explosive growth in art, writing and theater; hybridization and tension thanks to Jewish and north African cultural influences in Spain; and also there’s the disturbing effect of inbreeding on the Hapsburg family jaw. Plus, iconoclasm and poop jokes.

By all accounts young Teresa came into this environment lovely, smart and strong-willed. She recounts a story from her childhood in which she and her brother decided to run away to be martyred by the Moors; they were caught at the edge of town by an uncle and marched back home. (Whether you take this as evidence that she was particularly pious or a born shit-stirrer – or both – is up to you.)

In her teens, Teresa’s frazzled dad sent her to a convent, which at the time wasn’t the austere and virtuous place you might think. In fact, in the early modern era, convents were often basically boardinghouses for wealthy girls, known for comfort and laxity of discipline – biographer Cathleen Medwick noted that nuns often “enjoyed more freedom than married women.”*

Teresa was plagued by poor health throughout her life, and she went between religious life and periods of recuperation at home before finally actually asking her father to join a convent (he resisted, as she was of marriageable age). She ultimately went to the Carmelite order, and discovered that her religious life was anything but pedestrian.

Teresa’s writing presents a vivid and disturbing inner landscape – through meditative prayer she became one with God, chatted with demons, waged war against false visions and temptations. In the pre-eminent mystic experience of her life, called the transverberation, Teresa described a supremely beautiful male angel who pierced her heart with an iron lance – a nearly erotic experience later memorialized by the sculptor Bernini in marble and gold.

This was not the usual fare for the mentor priests who heard Teresa’s confessions, and they asked her to set her experiences down on paper as a result (we have much of her writing thanks to these requests). Not only could these priests encourage writing as therapy, it was a convenient way to see if Teresa was suspect in the heresy department.

Teresa combined her native intelligence with introspection and pragmatism. She was smart, acutely aware of her own physical and societal limitations, challenged by the depth and breadth of her visions, and eager to survive in an environment that resisted change. She made considerable efforts to write down her thoughts in a way that was honest yet unlikely to raise the eyebrows of her male confessors, often through calculated self-deprecation (i.e., “hey, I’m just a modest woman and I never went to college like you wise gents, but by the way I was one with the triune God this morning…”).

What did it mean to be a mystic, and a woman mystic, in the early modern church? As Teresa got older, and especially as she grew into the deep and consuming religious life of her middle age, she retained a winking sense of humor and a talent for navigating social structures, but was also plainly vulnerable and often challenged by doubt, ill health and the struggle to communicate her experiences of the divine. She wrote at length about the role and vindication of suffering, longing to give purpose to her self-doubt and chronic illness and to trust that she was serving God well despite opposition.

There are parallels to be found in Mother Teresa of Calcutta – when journals were released after her death, many were surprised to learn that a woman thought of as so unfailingly faithful was in fact privately unable to shake dark thoughts. The two Teresas share highs and lows: commitment, faith and reform placed aside near-crippling doubt and loneliness.

Inspired by the immediacy of her visions and familiar with the convents of the time, Teresa led reform measures to bring the Carmelite sisters more in alignment with the order’s austere founding values. Along with St. John of the Cross, who did similar work with Carmelite men, she is the founder of the discalced (“shoeless”) order, who embraced prayer, poverty and quiet dedication and who sought a paradoxical abundance in simplicity. She wrote encouraging texts for her warrior Carmelite sisters, traveled frequently and advocated for religious reform until her death at the age of 67.

It’s amazing to think on all of the ways St. Teresa seemed ahead of her time: she was great at pithy statements, told everyone they really should meditate, made her way as a woman in a restrictive society, and worked tirelessly to reform an entrenched lazy organizational culture.

In her own lifetime Teresa of Avila was counter-cultural, even risky in the eyes of the mainline church; and yet time validated her vision (in both senses). She was made a doctor of the Catholic Church in 1970 – only one of two women to be so named at the time.

“God protect me from gloomy saints,” she once said. She certainly did her part.

Fun Facts:

The Bernini sculpture of the transverberation is, in fact, pretty sexy.

The Catholic history and culture of saints’ relics is creepy and FASCINATING. Some saints’ holiness is said to be proved by the fact that their bodies do not decompose after death. Teresa’s incorrupt heart is held in the Carmelite convent at Alba de Tormes in Spain, and some say you can see the scars of the transverberation.

Teresa’s family were conversos – historically Jewish families who had converted to Christianity to avoid social pressures. “Limpieza de sangre,” or blood purity, was a big deal in early modern Spain. Teresa didn’t speak much about this aspect of her background, but she still likely had to privately contend with popular conceptions of conversos who chose religious life – there was a lot of skepticism about converts’ sincerity.

Teresa wrote in the style of popular chivalric novels like Amadis of Gaul and (later) Don Quijote, describing her nuns as warriors who protected a crystal castle of the soul. Not only was this pretty cool, the militarization of meditation made the contemplative life accessible and interesting to a wider audience.

Biographers all make note of the paralysis and coma Teresa suffered early in her life, the latter was so severe that onlookers (incorrectly) thought her dead and poured wax over her eyes in line with burial custom. Teresa’s lifelong health struggles were complex – she had so many symptoms and such great pain that it is hard to figure out what her diagnosis might have been. Suggestion range from thyroid disorders and epilepsy to the suggestion that her ailments were psychosomatic.

The Groucho Marx of saints? In addition to the (possibly apocryphal) “gloomy saints” quote, she once famously noted “There is a time for penance and a time for partridge.”

Additional reading:

Teresa of Avila, La Vida and the Interior Castle

Jodi Bilinkoff, The Avila of St. Teresa – Religious Reform in a 16th Century City

* Cathleen Medwick, Teresa of Avila: The Progress of a Soul

From Commonweal magazine.