Have a drink with: Astronauts Charlie Brown & Snoopy

Just don’t ask about kicking a football in zero-G.

Ask them about: getting America in the mood to fly again

I’ve got space on the brain. There’s New Horizons doing its Pluto drive-by, and my toddler running around with a plastic pail on her head insisting she’s going into orbit, and a Discovery documentary on TV that convinces me of nothing so much as the plain audacity of the early space program: basically a handful of men trusting to fate whilst strapping themselves to a giant directional bomb.

I am perpetually amazed with spaceflight but also terrified, since I like many others of my age group watched Challenger explode on live television in my elementary-school classroom. In the Challenger accident, NASA lost astronauts for the first time since the Apollo 1 fire of the late 1960’s, in which three astronauts were killed in a launchpad test of their vehicle. In coping with the deep personal, social and institutional trauma of both accidents, NASA went through a very similar process of examination and rebuilding, but that isn’t where the similarities end. In preparing for the return to manned spaceflight, NASA had some trusty allies: a boy and his beagle.

At the start of 1967, the U.S. space program was moving at, pardon the pun, a rocket pace. In the much-documented effort to beat the Soviets to the moon, NASA had successsfully made progressively lengthier steps into space in preparation for lunar missions.

On January 27, 1967, the crew of Apollo 1 entered their vehicle for a “plugs-out” pressurized test of the ship to simulate launch countdown. What should have been a routine test turned disastrous when a fire sparked in the command module, which ultimately killed astronauts Virgil “Gus” Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee. The Apollo fire shocked NASA and the American public, who had come to view the agency as a shining public example of American technology and ingenuity.

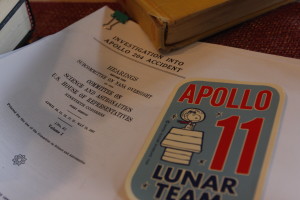

Investigation of the accident proceeded quickly, placing blame on a number of contributing factors, including “vulnerable” wiring, the presence in the cabin of of highly flammable components like Velcro, and the astronauts’ inability to open the capsule’s hatch due to the simple fact that the door swung inward, not outward. The fire’s spread and impact was aided by the cabin’s pure oxygen environment (then considered an advantage for astronaut alertness and cabin weight), leading one Congressman to note in investigative hearings:

“I understand in Fort Lauderdale there is an ordinance that you cannot have bottled gas within 10 feet of an electric-type heater in your house. Now, if that is good for a house, why isn’t that good for the capsule?”

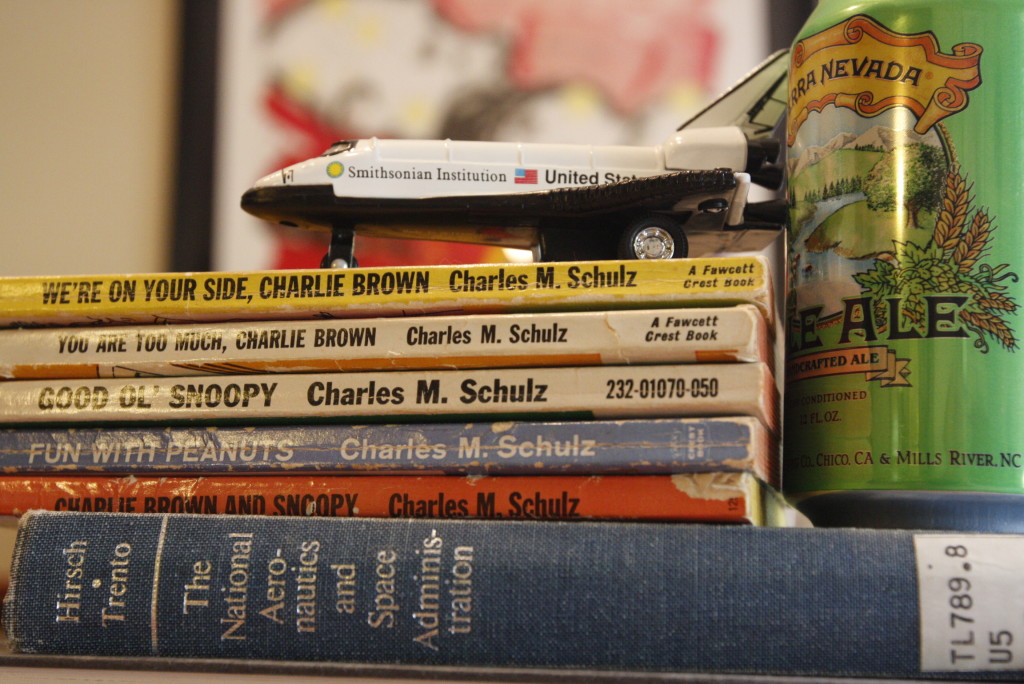

How did NASA cope with the tragedy? In addition to matters practical, political and cultural – the latter embodied in Gene Kranz’s demand for a “tough and competent” organization, NASA enlisted Peanuts cartoonist Charles Schulz to help give the return-to-flight safety effort some team spirit.

Much has been written about Schulz’s contributions to NASA, and their very real value in creating much-needed enthusiasm and attention to improvement in the two years it took to get back to manned flight (e.g., Mashable, iO9, the Schulz Museum, NASA History). Astronauts carried plush Peanuts toys; the black-and-white caps worn underneath EVA helmets were nicknamed “Snoopy caps” after the dog’s droopy ears; Schulz drew comic strips in 1968 that showed Snoopy flying his doghouse to the moon. When the program regained its footing and Apollo 10 ran its dress rehearsal mission for the moon landing, it sent transmissions back to Earth calling the command module and lunar lander “Charlie Brown” and “Snoopy.” (Snoopy’s successor was the Eagle, presumably because “Snoopy has landed” somehow would not seem sufficiently dignified.)

Now fast-forward to 1986. Like Apollo after the fire, the shuttle program was devastated by the loss of its crew, and grounded for more than two years in preparation for return to safe flight. Also like the Apollo program, NASA and its contractors underwent lengthy critical review that exposed significant, disappointing oversights and shortcomings in the space program and the vehicle’s infrastructure – perhaps most memorably demonstrated by physicist Richard Feynman before Congress, when he dunked a rubber “O-ring” seal into a cup of ice water to show its inflexbility under cold-weather conditions. The O-ring became to Challenger what the pure-oxygen environment was to Apollo – painfully destructive, “low-tech,” and something that seemed easy to have avoided.

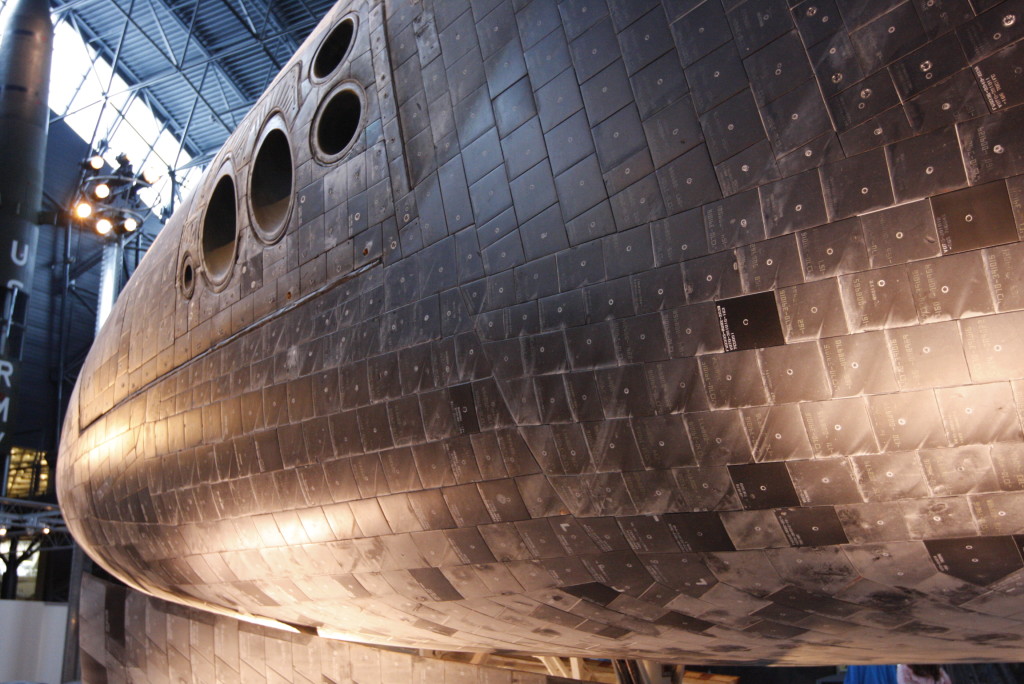

The shuttle Discovery launched for mission STS-26 on September 29, 1988, returning NASA to flight.

Not six weeks later, a Peanuts animated series about American civics aired an episode entitled “The NASA Space Station.”

The only forward-looking episode of the series (others talked about the Wright brothers, the Mayflower, the Constitution and the Transcontinental Railroad), it shows Linus falling asleep at work on a school project to build a diorama of a NASA station. He dreams about the Peanuts gang as the 90-day crew of a working space station, yawning as he falls asleep that “America’s next space station will be launched in the mid-1990’s.”

Hijinks predictably ensue (Pigpen taking a space-shower, anyone?), but so do some admirable depictions of what space travel presumably has to offer humanity: Lucy van Pelt as the station’s female commander; Franklin the social scientist bringing racial diversity to the crew; Sally delivering a speech about boundaries not being part of the distant beauty of Earth, recalling the Apollo 8 crew’s wonder at “Earthrise.”

In the end, Charlie Brown himself becomes the emblem of the optimistic U.S. return to space.

Patty: “Well, you know, he doesn’t always do the right thing, and I can still strike him out on three pitches.”

Lucy: “So?”

Patty: “Well, I gotta hand it to him. He keeps on trying. He doesn’t give up. He just keeps plugging away. So I guess that’s what we all have to do back on earth.”

Good ol’ Charlie Brown.

Fun Facts:

Pigpen isn’t wrong; how to shower in zero-G is a real thing of concern.

Linus turned out to be pretty close: the International Space Station was launched in the late 90’s, with crew going aboard in 2000.

In the fine tradition of Peanuts and jazz music, Dave Brubeck did the soundtrack to “This is America, Charlie Brown: The NASA Space Station.”

When you get down to it, humans first got into space on less technology than is in my iPhone – heck, watch old videos of the Mercury Seven and John Glenn is riding into Earth orbit in a piece of equipment with less cushioning and fewer safety rules than a ride at Six Flags.

I’m impressed with the space shuttle’s lengthy service period, which occasionally makes me both admire and worry about our societal intelligence level: by the twilight of the shuttle program, at which point the loss of Columbia had made clear that subsequent flights would only carry unacceptably increased risk factors, we were basically still driving a 1970’s car. Yes, we got rid of the cassette player and reupholstered the thing, but the idea was a few decades old. In the end, the shuttle was an astounding idea – but was it a good one at all? The idea of a reusable spacecraft certainly pushed things forward, but there were many safety criticisms particularly in the post-Columbia era, in comparison to Russian Soyuz designs, and in the larger context of NASA leadership.

Snoopy is still out there.

How do we look at the modern space program and its recent cargo provider failures?

Forbes on changes to the Peanuts brand and its marketing.

If you are the superstitious sort, you may want to recommend against space launches in winter: the Apollo 1 fire, Challenger’s destruction and the loss of Space Shuttle Columbia all occurred in the span of a few weeks in January – February.

Additional Reading:

“This is America, Charlie Brown: The NASA Space Station” is available via Amazon Instant Video, on DVD or at Dailymotion.

The Apollo 204 (Apollo 1) accident: at Scientific American, NASA, Congressional hearings, and the Board Report.

NASA History on Twitter.

People must, of necessity, research things like farting in space. Mary Roach’s book Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the Void humanizes the space industry, looking at its oddities. And as with many things, the oddities are what make it all so interesting – not for a minute does it make anything less noble to realize people made careers of figuring out astronaut food, or how to poop in space. Entire studies are done on people confined to bed to see about atrophy on long-distance voyages.

Craig Nelson, Rocket Men

Space Shuttle Legacy: How We Did It and What We Learned, Roger Lunius et al, eds.

When We Left Earth dvd documentary series