Have a drink with: David Bushnell

Damn the torpedoes.

Ask him about: The one that got away

Folks in Warrenton, Georgia were understandably sad when Doctor David Bush passed away in 1826. Single and in his eighties at the time of his death, the old man was a local institution: in more than thirty years in town Bush had practiced medicine, been active in local politics and even set up an area school. Folks knew the local doctor was quiet, civic-minded and accomplished.

So his secret identity may have come as a bit of a surprise.

This post brought to you at the suggestion of my dear friend Natalie: ace tax lawyer, Bollywood dance aficionado, history fan and all around first-rate human. For this year’s version of the noted GISHWHES scavenger hunt, Natalie put together an inspired historical rap based on the life and times of David Bushnell, a Connecticut native who contributed to the Revolutionary War effort by developing one of the world’s first military submersibles – and who for unknown reasons retired to Georgia to live out his years under an assumed identity as a small-town family doctor.

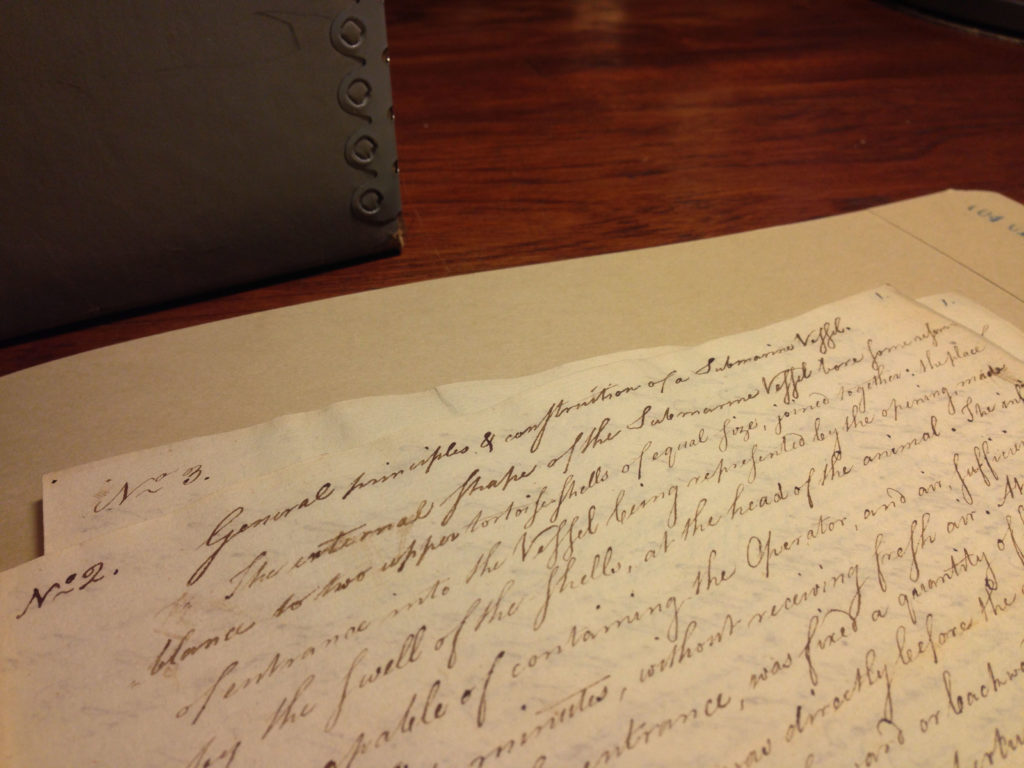

David Bushnell was born in 1740, into a bookworm’s nightmare: oldest child in a farming family. Unmarried, unfulfilled and stuck at home through his twenties, Bushnell jumped at the chance to escape: when his father died, David promptly sold his share of the farm to his brother Ezra and raced to Yale to start college at 31 years of age. (And while you spent college figuring out ways to shotgun beer out of a watermelon, Bushnell discovered how to make gunpowder explode underwater.) Making up for lost time, Bushnell worked obsessively on designs for a submersible he believed could have military impact – and after graduation he returned to southern Connecticut to build, test and tinker. Through years of patient work Bushnell had the help of collaborators who brought his ideas to life, particularly Isaac Doolittle, a New Haven clockmaker who was indispensable in machining the Turtle’s vital mechanical parts; and Benjamin Gale, a local doctor and science enthusiast who in 1775 assured Ben Franklin:

“This story may Appear Romantic, but thus far is Compleated and All these Experiments above related has been Actually Made, He is now at New Haven with Mr. Doolittle an Ingenious Mechanic in Clocks &c. Making those Parts which Conveys the Powder, secures the same to the Bottom of the Ship, and the Watchwork which fires it.”

Bushnell’s creation, a sub named “The Turtle,” was a wooden sphere with just enough room for an operator and some basic hand-crank machinery. It provided the operator with about half an hour of air supply, and was built to attach explosive mines to the underside of unsuspecting enemy ships. This had the potential to be a complete game-changer, particularly with the British throwing their naval weight around New York – but while David Bushnell was ingenious and driven, he also had rotten luck.

Bushnell’s brother Ezra got sick when he was to pilot the Turtle on its maiden voyage, so David quickly trained Ezra Lee instead. Lee came up directly under the British flagship HMS Eagle, but ran into a sheath of metal attached to the bottom of the ship and failed to attach his payload. Two later attempts to attack the British also failed – one resulting in the famed “Battle of the Kegs,” during which live torpedoes bobbed willy-nilly down the Delaware River. Writing to George Washington, Bushnell protested that his Corps of Sappers and Miners (what we might today call the Corps of Engineers) were treated by lower-ranking officers as glorified ditch-diggers.

It’s easy to see him wondering: if he had managed to sink the Eagle, would he have been a servant hero of the new nation? If the Battle of the Kegs had gone more menacingly, would the tide have turned? Had Revolutionary brass legitimized the corps of engineers, would he have had a smoother, more posh career laid out for him?

After the Revolutionary War, Bushnell was worn out and broke. He eventually settled in Georgia, where he practiced medicine under the name “Dr. Bush,” and continued quietly working on sub warfare. Bushnell’s executor George Hargraves “leaked” a letter to Thomas Jefferson in 1814, pushing his friend’s case:

“The enclosed description and drawing of a Torpedo is an original paper which has lately fallen into my possession. Not being a judge of such matters, I shou’d probably have thrown it by as useless paper had I not known the Inventor to be a man of science, and more capable, in my opinion, of judging correctly of the efficacy of such things than any other person I know of.”

Hargraves warns, though:

“From that part wherein your name is mentioned, you will readily conjecture who the Inventor is…I have no objection to your communicating the plan to any one you think proper, but for particular reasons, I beg of you to conceal his name, and to withhold from publick view that part which may lead to a discovery.”

And why Bushnell was so secretive, we don’t really know. Not until after his death was his true identity made public. An 1826 letter from Hargraves states: “The Deceased has resided in this State near forty years, and for reasons probably known to his friends and relations in Connecticut has concealed his Name & residence. He never informed me very particularly of his reasons for so doing, but I always conjectured [from] conversation generally, that he got duped and cheated by a rascal, and found it prudent to absent himself from a dishonest Creditor.”

Fun Facts:

The January 1778 “Battle of the Kegs” had a Looney Tunes element to it – having miscalculated the tides and the behavior of the floating bombs, Bushnell failed to bomb strategic targets. This didn’t stop the British from getting men and cannon ready, and shooting frantically at anything that floated. The only casualty was a bystander who tried to pull a mine out of the Delaware River. This inspired a poem by Francis Hopkinson, entitled The Battle of the Kegs:

These kegs, I’m told, the rebels hold,

Packed up like pickled herring,

And they’re come down, to attack the town,

In this new way of ferrying.

The Connecticut shoreline has been submarine country for centuries, from Bushnell in 18th century Westbrook and Old Saybrook to the modern-day General Dynamics/Electric Boat, which since 1899 has built the nation’s military submarines. In Groton you can visit the Submarine Force Library & Museum, see a model of Bushnell’s Turtle and step aboard the USS Nautilus – the world’s first nuclear submarine, which during “Operation Sunshine” completed an undersea voyage to the North Pole.

And yes: the Nautilus has cup holders.

Critics aren’t shy about saying Bushnell was no innovator, that the principles behind the Turtle were already known to 18th century science. Alex Roland mentions the role and fortuity of the Yale library in exposing Bushnell to items like Royal Society works, a then-popular Gentleman’s Magazine article and Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis, which posited not only the existence of submarines but suggested construction methods. This does not change the fact that creative theft is a cornerstone of innovation – or, put another way, reading some articles is not the same as BUILDING A FRIGGIN’ SUBMARINE.

Six Degrees of Submarine: At one time David Bushnell lived with fellow Yalie Abraham Baldwin in Georgia. Baldwin’s brother-in-law was Joel Barlow, who at one point lived and worked with Robert Fulton, who built the Nautilus for Napoleon.

Additional Reading:

David Bushnell to Thomas Jefferson, October 13, 1787

Nathaniel Philbrick, Valiant Ambition

Roy Manstan and Frederic Frese, Turtle: David Bushnell’s Revolutionary Vessel

Naval History and Heritage Command, The Submarine Turtle: Naval Documents of the Revolutionary War

James Thacher, A Military Journal during the American Revolutionary War, from 1775 to 1783