Have a drink with: John Tyler

His Accidency

Ask him about: Sick of that song yet?

In the anonymous New York Times opinion essay about staff dissent within the White House published earlier this month, the author mentioned (among many other things) deliberation over use of the 25th Amendment in response to perceived presidential instability.

To be fair, this is not a new topic: the the 25th Amendment has been a common topic in shouts and whispers over the past two years as pundits consider whether its terms would or wouldn’t realistically attach to the current occupant of the White House.

The 25th Amendment to the Constitution was passed in 1967 in direct response to the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and the questions involved had well predated the 25th Amendment even if they had not been presented so directly: what to do when the Presidency changes fundamentally and irrevocably, due to death, removal, resignation, or disability?

Dealing with matters of succession and power transfer, the 25th was invoked in the 1970s around the Nixon administration, and is occasionally put into action when a sitting President is temporarily incapacitated (despite the promise of intrigue and drama inherent in the amendment, in reality it’s been used, for example, to cover the duration of each of the Bush presidents’ colonoscopies).

But for the first word on the matter of presidential succession, you’ll need to go back to 1840 and then-Vice President John Tyler, who set up a century-long American precedent on succession that boils down to a very Trumpy word: MINE.

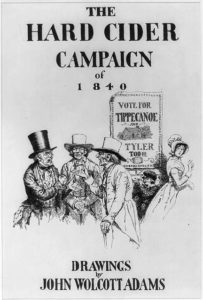

In the 1840 election, often considered the first to operate in a modern mode for its combination of media coverage and nasty name-calling, Whig candidate William Henry Harrison ran against incumbent Democrat Martin van Buren. The Whig camp decried van Buren as a snooty aristocrat who had badly bungled the economic depression of the Panic of 1837, and van Buren’s supporters labeled Harrison as a country yokel, the sort of unambitious rube who would be foolishly happy to sit his days on the porch of a log cabin taking his pension and drinking cider. For the record, both of these portrayals were essentially fictional – Van Buren was no more an aristocrat than well-to-do Harrison was a hayseed – but what matters is that the Harrison camp was more than happy to style their candidate as a rugged man of the people, and the “log cabin and hard cider candidate” was born.

And if we know anything about American politics, it’s not to underestimate the power of an angry blue-collar voting bloc handed a meme on a platter. “It became a log-cabin campaign,” wrote one late-19th century account, “and demonstrated the power of the people who lived in log cabins when once aroused to action.”

Harrison handily won the election, gave the longest inauguration speech in American history (nearly two hours), and in grimly poetic retribution, died a scant month later of pneumonia.

He was the first president to die in office, and there was no clear guidance on what to do next. Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution reads:

“In Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President…”

This only partially helps: does the Vice President simply assume the “Powers and Duties” of the office, or the office itself? Many of the political players in Washington, including a fair portion of Harrison’s cabinet, felt that the Constitution set up an “acting presidency” whereby Harrison’s running mate John Tyler would retain the office of Vice President while discharging relevant presidential duties.

Tyler liked Door Number Two better. Without waiting for input or approval, he arranged to take the oath of office as soon as possible and assumed the full office of President of the United States. He was, therefore, the first Vice President to move into the American presidency absent election, and did not escape some serious eye-rolling over his tactics: opponents jokingly called him “His Accidency,” and you can imagine how much he loved that.

History has not treated John Tyler kindly, and not for nothing: Tyler was kicked out of his own Whig party for being too trigger-happy with veto power; he drew impeachment resolutions; all of his cabinet save one member – Daniel Webster – quit in frustration with him; and he ended his life as an elected member of the Confederate legislature. But as much of a turkey as he arguably was, he established the precedent that was used to ensure continuity of American government after the subsequent deaths of Presidents Taylor, Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley, Harding, (FD) Roosevelt, and Kennedy.

The 25th Amendment formally codified the “Tyler Precedent,” clarifying that on the death or removal of the President, the Vice President formally accedes to the office; while in the case of an incapacitated Commander in Chief, the Vice President acts on a temporary assumption of duty.

Fun Facts:

John Tyler died in 1862, and he still has two living grandsons. Let that one sink in.

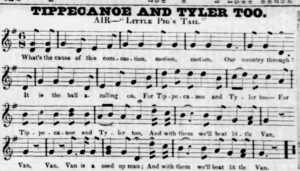

Even more famous than the log cabin line was the 1840 campaign slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too,” which elevated Harrison as a war hero – he had led forces against chief Tecumseh at Tippecanoe in an ugly battle that partially precipitated the War of 1812. (Tyler predictably hated being “Too.”) The campaign slogan in turn gave rise to the first real American campaign song, a rousing number packed with inside jokes about national politics: Harrison, the hero of Tippecanoe, “Little Van” Buren, and the “Locos.”

The “Locos?” The Loco-Foco party were a radical wing of the Democratic party in the 1830s and 1840s, named for a strike-on-surface self igniting match. Rooted in New York, the party’s name allegedly came from a Democratic nominating meeting at Tammany Hall in which the establishment shut off the gas lights in an attempt to call an end to the meeting, and agitators defiantly struck “loco-foco” matches.

Tippecanoe and Tyler Too? It’s also a They Might Be Giants song.

Additional Reading:

Jan R. Van Meter, Tippecanoe and Tyler Too: Famous Slogans and Catchphrases in American History (2008)

Anthony Banning Norton, The Tippecanoe Campaign of 1840 (1888)