Have a drink with: The Liberty Loans

Some drill, some till, and some produce the dollar bill.

Ask them about: buying World War I for Christmas

This season not only marks the centennial of the Armistice that brought an end to World War I, but also of the massive public investment campaign that made American involvement in the war possible. In four bond drives conducted in 1917 and 1918, the American public stepped up to fund the war effort by purchasing some $17 billion dollars of U.S. government securities popularly known as “Liberty Loans.”

And if you asked Secretary of the Treasury William McAdoo in December 1917, he’d tell you that the hottest Christmas gift around was a Liberty Loan, because nothing screams “holiday spirit” like punching the Kaiser in the snoot.

The idea behind the loan program was to use public support and funds to bear the main burden of financing American involvement in the war: essentially, crowdfunding the national war effort. As an added benefit, if successful, the loan program would work to turn the American economy from its consumer focus over to war production. Advocates for the Liberty Loan program considered it best to borrow most of the money needed for the war from the American public, rather than simply to print more currency (risking inflation, as the “greenbacks” of the Civil War had done) or raise funds solely through taxation (pissing people off).

No age, demographic or industry was immune to bond marketing, or to the social pressure to participate. Lush posters shouted from every wall about what a Liberty Loan might do: “Halt the Hun,” preserve democracy, support friends and family serving abroad. A-list celebrities assisted the massive crowdfunding effort, from “saleslady de luxe” Mary Pickford to titans of silent film like Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks, who in April 1918 packed Wall Street with 20,000 people in a single bond rally. In 1917 a captured German submarine (playfully rechristened “U-Buy-A-Bond”) was put on display in Central Park, a tour of the interior free to any spectator wearing a Liberty Loan purchaser’s button.

In October 1917 the U.S. had been involved in the war for a short but already expensive eight months, and the government was urging Americans to start their Christmas shopping early, in an effort to divert materials and delivery capacity to serving the war effort. With holiday marketing in full swing by October, and the Second Liberty Loan drive underway in an effort to raise nearly four billion dollars, loan boosters naturally asked, well, wait: do we all really need more crap? How about a Liberty Loan Christmas?

New York’s banking community obliged by agreeing to pay their employees’ holiday bonuses in Liberty Loans; and in newspapers nationwide, Treasury Secretary McAdoo urged everyone to stuff their stockings with gifts for Uncle Sam: “Let every patriotic American this year determine not to waste money on Christmas gifts of no value, gifts that would merely indulge appetite or vanity.” Asking Americans to come together in sacrifice, McAdoo wrote for the United Press that “By the destruction of the kaiser’s brutalized rule of the bayonet the more quickly peace on earth, good will toward men will be restored.”

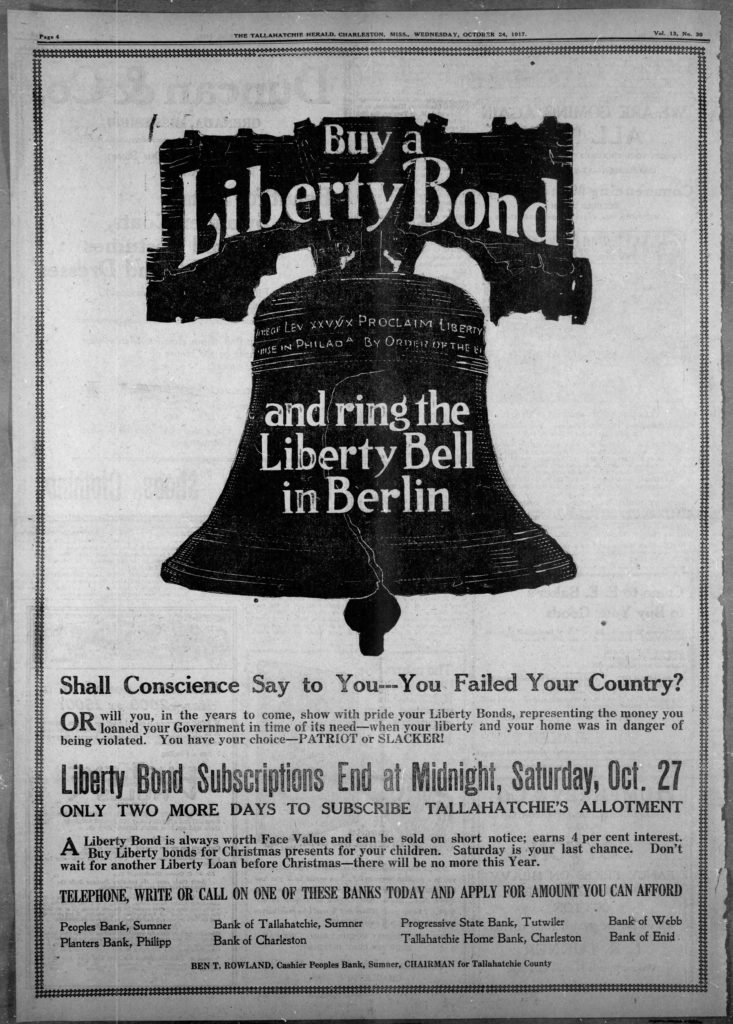

Not everyone went for a Charlie Brown Christmas level of poetry, though. Urging families to buy Liberty Loans as Christmas gifts for their children, a full-page ad in the Tallahatchie Herald, emblazoned with the Liberty Bell, simply hollered “You have your choice – PATRIOT or SLACKER!”

Courtesy newspapers.com

Don’t be a slacker. This holiday season, spare some brain space to think about what Christmas was like a hundred years ago: for a couple suggestions, you may want to check out Peter Jackson’s remarkable documentary They Shall Not Grow Old, now in a limited theatrical run; or just read up a little on World War I.

Merry happy.

Fun Facts:

While the Treasury Department set the minimum bond purchase amount at $50 to encourage broad participation, even this was an intimidating amount for most working-class Americans in 1917, generally the equivalent of a few weeks’ wages. To get more people on board, “thrift” or installment programs were offered by banks, brokers and large companies (the Connecticut insurance industry was especially involved) to make purchase possible for the working public. In addition to its own installment plan, the federal government offered a “thrift stamp” program through which individuals could purchase low-value stamps, paste them to a special card, and exchange the stamps for a certain bond value when a set amount accumulated. Some of these thrift stamps were themselves holiday-branded, with verses like:

“The gift of gifts I send to thee

A Thrift stamp for your Christmas tree;

Tall oaks from little acorns grow –

It’s up to you to prove it so.”

Women were key to the success of the loans, as contributors and highly energetic sales staff in homes, workplaces and community and civic organizations. Fannie Bulkeley, who chaired the Connecticut state Woman’s Liberty Loan Committee, was a familiar face at the “Liberty Cottage” that sold bonds in downtown Hartford, and of one sales event mentioned the very holiday-appropriate can-do spirit she and her colleagues saw everywhere: “We are more than pleased with the result. Such a splendid spirit was shown by everyone in working on the campaign. What pleases us most is the sale of small bonds as it is the number that we wanted. In spite of so many calls upon everyone, they are always willing to do their share.”

Charlie Chaplin went so far in his support of WWI war bonds as to produce a short film of his own to support the war effort, entitled “The Bond.”

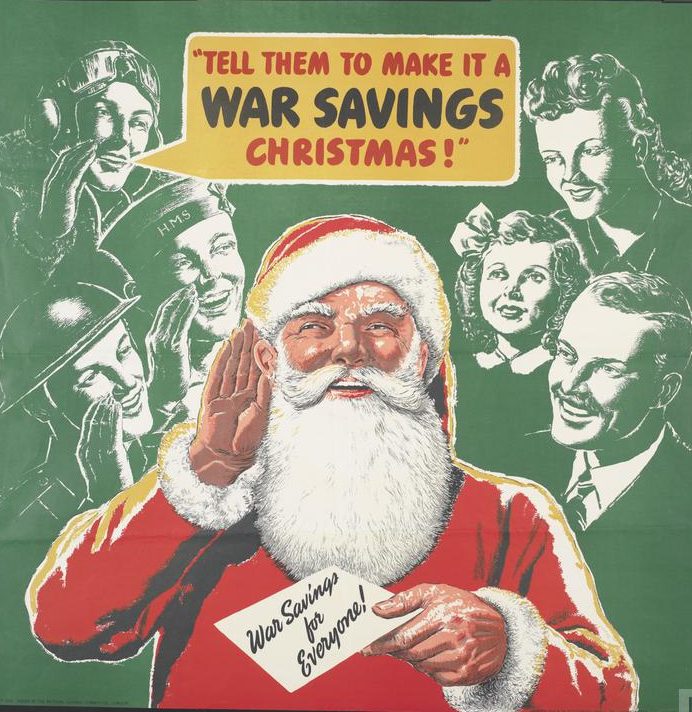

Later on, World War II bonds in the United States and in the U.K. would also embrace the Christmas spirit, urging holiday bond purchases with promotional posters that called war bonds “The Present With A Future.”

Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/33381

Additional Reading:

Dept. of the Treasury, The Second Liberty Loan of 1917: A Source Book (1917)

Labert St Clair, The Story of the Liberty Loans (1919)

Richard Sutch, “Liberty Bonds,” Federal Reserve History