Have a drink with: Napoleon Sarony

Work with me, darling.

Ask him about: Oscar Wilde, cover girl

The author of an interview with the photographer Napoleon Sarony, published in the June 1895 edition of Decorator and Furnisher magazine, was clearly excited about getting to meet such a famous figure. In the style of the modern celebrity profile, with luxe asides about the subject’s choice in clothing, food or furniture, the writer gushes that Sarony’s apartment is lavishly decorated, stuffed with Rococo furniture, Latin American pottery, even an Egyptian mummy in its sarcophagus. Fat portfolios of photographs nod to Sarony’s profession, with images of “every known celebrity that has either been born or set foot upon American soil, as well as thousands of photographs of the rank and file of American Democracy.”

There is more than Sarony’s luxe eccentricity to mention, though: the article opens with a mention that the state legislature, under the thrall of Anthony Comstock’s anti-vice movement, was then entertaining the idea of a law to prohibit any representation of the nude human figure from going on display (and a catty aside that the law’s advocates were not simply seeking legislation, but “incidentally some notoriety for themselves.”).

Surely America’s most flamboyant celebrity photographer would have an opinion on the Comstock crusaders?

The key, he explained, was in portraying the nude as refined, innocent and graceful – free of seductive gazes or vulgar poses, presented as naturally as a flower in nature. Citing his own work, he explained: “I think my work proves that photography has aspects personal and individual apart from mechanical considerations. The camera and its appurtenances are, in the hands of an artist, the equivalent of the brush of the painter, the pencil of the draughtsman, and the needle of the etcher.”

He would know: the U.S. Supreme Court had told him so.

In the early 1880s, when Oscar Wilde was a much anticipated arrival to New York City, the writer and bon vivant had visited Sarony’s studio to have a series of portraits taken – Sarony had not only begun to build up a solid celebrity clientele, in the mode of modern photographers and tabloids he often paid handsomely for exclusivity around the images. When one of the photos was taken up by a city department store as an advertisement in an effort to capitalize on Wilde’s sensational popularity, Sarony sued, accusing the store’s printer of infringing copyright. On appeal to the Supreme Court in 1884, the printer argued that photographs were ineligible for copyright protection, because they were mere reproductions of nature, created by the operator of a machine. For many people, the idea that Napoleon Sarony could claim ownership of his photograph was ridiculous: tantamount to somehow saying he owned and had created Oscar Wilde himself.

And indeed news coverage of the case made light of this question, summarizing the dispute with headlines that hollered: “Who Invented Oscar Wilde?”

The dispute seems quaint, even silly, from a modern perspective, but in the late 19th century when photography was both new and alluring, there wasn’t a lot of common agreement or understanding around how it worked or what it might be used for. Photographs froze time and trapped circumstance in ways that traditional representative art had never achieved. To be honest, not many people fully understood the new technology or how it worked; and many felt that a photographer was, rather than being an artist or craftsman, just a glorified button-presser. The court dug into this question.

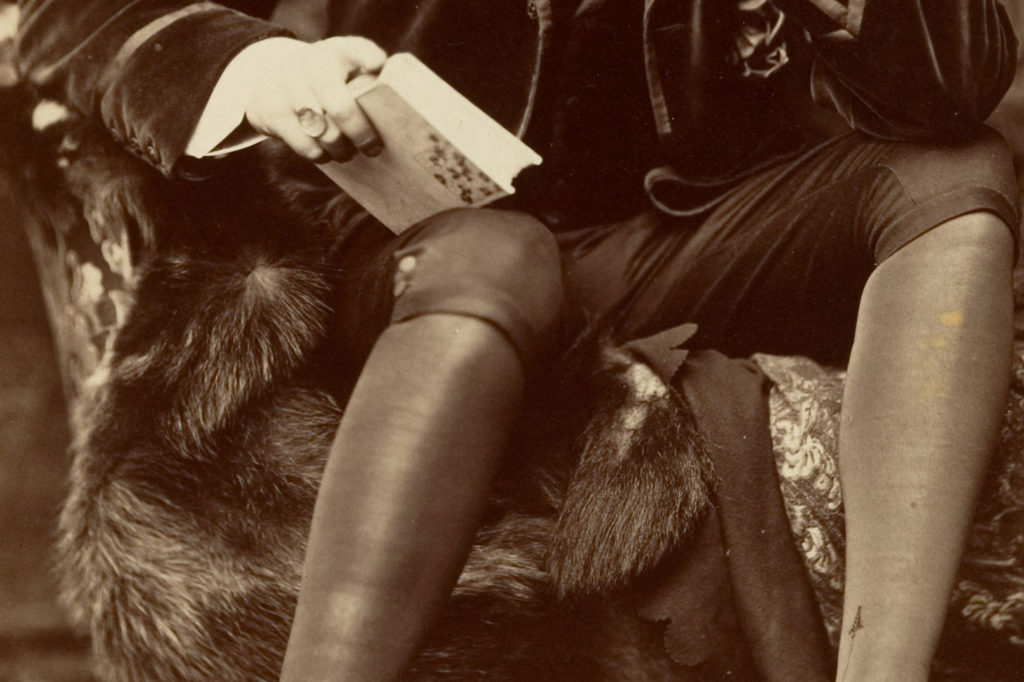

Sarony’s argument, in favor of copyright protection, was that he had made specific choices in the creation of his image: he posed Oscar Wilde just so, encouraged him to wear particular shoes, silk stockings or jackets, and decorated the studio with lighting and drapery to achieve a specific look and feel. He did not invent Oscar Wilde, but arrange the writer he certainly did.

The Supreme Court agreed. In 1884 American law first extended copyright protection to photographs, declaring them original works of art into which the photographer inserts agency and discretion.

Sarony clearly enjoyed having legal validation that he was an auteur, an artiste, an authority. He also returned the favor when, in 1890, he photographed the justices of the Supreme Court in slightly more luxurious setting than chambers might afford – Justice Harlan throwing an elbow over an ornate wooden chair, and the justices flanked not by sober wooden paneling or law reporters, but by some softly textured ferns, a column and a velvet curtain.

How original.

Fun Facts:

There was no doubt that Sarony exercised discretion in the composition of his photographs. He was in fact such a stickler for detail that he, having asked the actress Sarah Bernhardt to remove her stockings for a shot, folded a dollar bill and stuck it between Bernhardt’s big and second toes in order to achieve just the right pose for her “beautiful and shapely feet.” (She, at the request, complied after a “French shrug, denoting curiosity and doubt.”)

On copyright: happy January, it’s public domain time in America!

Sarony’s photo of Oscar Wilde #18 was the image behind the lawsuit, but Sarony took more than two dozen different posed shots of the writer, which you can review at the site Oscar Wilde in America.

Copyright law doesn’t stop there in terms of photographs and originality, though: in the digital area, case law got into the idea that a photo that is meant to be a painstaking replica of an original (to wit: reproductions of famous artworks for a database or CD-ROM – yes, this was the 1990s) is a “slavish copy” and lacks the necessary originality to give rise to copyright protection.

The Supreme Court could not have picked a better trait to recognize in Sarony than originality. One celebrity item talking about the photographer remarked, “Sarony could no more have helped being picturesque and even theatrical in his appearance and manner than he could have helped breathing.” Understatement was not his forte: he loved to wear thigh-high cavalier boots, a thick sculpted mustache, and was often shown wearing a favorite red velvet fez and an astrakhan collar. He was fond of a certain soft luxury and classicism, and perhaps unsurprisingly, this led to a very identifiable photographic style. The caricaturist Thomas Nast said that “He made everyone he photographed look like Sarony. You know what I mean. The same feeling was in every picture.”

Sarony was indeed the Annie Leibowitz of the 19th century: a brief LA Herald obituary claimed that: “Next to Brady, he has probably photographed more celebrities than any other artist in the United States.”

Additional Reading:

Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53 (1884)

Mitch Tuchman, “Supremely Wilde,” Smithsonian Magazine, May 2004