Have a drink with: Elias Howe

Adventures in sewing: now with cannibals!

Ask him about: patent trolls

It’s kind of easy to knock Elias Howe, historically speaking. There is a statue of him in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where he is claimed as a famous son despite the fact that he was born in Massachusetts; he is largely credited with inventing the sewing machine despite the fact that he sort of didn’t; and some biographies describe him as a hero of the Civil War despite the fact that he was a 40-year-old private.

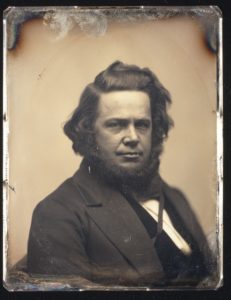

But let’s cut the guy some slack, really. Because there’s a lot to love about Elias Howe – and not just that he was solid Daguerreotype Boyfriend material:

This is a guy who created the United States’ first patent war, all while insisting his creative inspiration came from a dream about being held captive by cannibals.

Howe patented the idea for a sewing machine in 1846, believing that a mechanical means of sewing could beat the pants off of even the fastest hand-stitch seamstresses and introduce efficiency in all sorts of American textile production. The mythic backstory was first-rate: Howe claimed that he was stuck on the idea until one night, in a dream, he found himself kidnapped by a savage foreign king and told he had to produce a sewing machine in a day’s time or suffer death. Dream-Howe panicked until he noticed that the warriors snarling and poking at him carried spears with holes in the point. Waking in a flash, he realized that the solution to his design problem was to place the eye of the machine needle at the point, not in the larger heel as with hand-stitching.

A functioning machine, a United States patent and a solid captivity narrative did little to help Howe, though; the machine sold poorly, due to public skepticism, Howe’s insistence on steep license fees, and the fact that a rush of other inventors were eagerly coming up with overlapping ideas. Before long, a clutch of these inventors – among them Isaac Merritt Singer – were engaged in a nasty rash of litigation that kept them focused on fighting each other rather than developing and marketing their machines. (In modern parlance, this sort of inventors’ war is called a “patent thicket.”)

By 1856, the legal and financial landscape for mechanized sewing was so choked up that progress seemed impossible. The president of the Grover and Baker company proposed a solution to what folks came to call the “Sewing Machine War:” the major developers and manufacturers would call a truce, pool their patents and work together to enforce their rights. The “Sewing Machine Combination” was born. Until 1877, at which time most of the inventors’ patents expired, the Combination was the undisputed power in the industry – and Howe more than made up for the lean years in his life, insisting on sales royalties (which totaled nearly $2 million) as well as profit-sharing. He gave generously to the Connecticut infantry during the Civil War – providing horses for all of the officers of the 17th Volunteer Regiment, in which he served as a private (having declined the offer of a colonel’s rank, instead suggesting that his health and sense of honor better suited him to ride to and from Baltimore with war news) – and died in 1867.

If all of this has you particularly interested in historical sewing: space is still available in the Vintage Sewing Adventure, an April 2019 conference in Tulsa, Oklahoma run by my friend Lisa Neel in conjunction with her twin sister Lara – visit twinsnneedles.com for full details (see what they did there?).

Fun Facts:

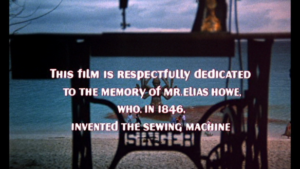

One of my favorite movies, the Beatles’ Help!, ends with the following delightful non sequitur:

Another innovation of this period was the marketing of sewing machines on payment plans: not only was it more financially palatable for most households than up-front purchase, it eased skepticism (Can women use machines? Is machine sewing a load of bunk?) by pushing “try before you buy” rental terms.

On August 24, 1861, very soon after the bombing of Fort Sumter, folks down in Bridgeport got wind of a planned secessionist rally on the Stepney Green in Monroe, Connecticut. As this was conveniently a short ride north of town, P.T. Barnum and Elias Howe decided this was an ideal chance to put their Union fervor on display, and the men headed to Monroe, joined by a few rowdy carloads of Northern soldiers on leave. They disrupted the rally, seized the stage, and when the crowd got testy, Howe allegedly hollered, “If they fire a gun, boys, burn the whole town, and I’ll pay for it!”

Barnum’s connection to Bridgeport’s sewing industry goes beyond his friendship with Howe. The showman’s investment in the development of industrial land in East Bridgeport was personally disastrous to the extent it contributed to his bankruptcy in the middle 1850s (due to faulty investments in the Jerome Clock Company) – but the vacant factory left in the wake was purchased by the Wheeler & Wilson Manufacturing Co., which was ultimately purchased by its competitor Singer in 1907.

Isaac Merritt Singer wasn’t a boring guy, either: one author describes him as a “bigamist who married under various names at least five women over his lifetime, fathered at least eighteen children out of wedlock, and had a violent temper.” *

Additional Reading:

Before the Hon. Philip F. Thomas, Commissioner of Patents : in the matter of the application of Elias Howe, Jr., for an extension of his patent for sewing machines : testimony taken on the part of the applicant, Elias Howe, Jr.

* Adam Mossoff, “The Rise and Fall of the First American Patent Thicket: The Sewing Machine War of the 1850s,” 53 Arizona Law Review 165 (2011)