Have a drink with: Jumbo

The Children’s Giant Friend

Ask him about: bath time in the Thames

There’s one conspicuous problem with the 1941 Disney movie Dumbo and Tim Burton’s remake, released last week: the elephant’s name is not, in fact, Dumbo.

The little elephant with the big ears is, in fact, given a family name when he is born, and Mrs. Jumbo’s baby is christened Jumbo, Jr. (The mocking nickname comes about when his giant ears are discovered.) This establishes Dumbo in the lineage of a real circus animal – the mighty Jumbo, P.T. Barnum’s prize African elephant. In 1941, when the original Disney film came out in theaters, Jumbo was still within fifty years’ living memory – and indeed, a fair swath of adult audience members were likely to have remembered seeing Jumbo as children on circus day, as the Greatest Show on Earth wound its way across America.

When P.T. Barnum secured him from the London Zoo, where he was known as the “children’s friend” for the rides he would give to young zoo visitors, Jumbo became the undisputed star of the circus, elevating the Barnum shows to an even greater level of cultural prominence.

Here are a few things you may not know about Dumbo’s famous patriarch.

1. In all honesty, Jumbo had a rough life. In the mid- to late 19th century, Indian elephants were reasonably common in shows and zoos, but African elephants were rare in captivity. To satisfy urgent (and profitable) demand, Jumbo was captured as a calf after his mother was murdered by mercenaries under contract to European animal dealers. In 1862 he was described as being about four feet tall, 500 pounds – a yearling runt, and not expected to live long. He nonetheless survived the trip through the Sudan to Western Europe, but did not impress the owners of Paris’ Jardin de Plantes. Having received a more compelling pair of calves, they traded Jumbo to the London Zoo for an ill-tempered Indian rhinoceros, two dingoes, a jackal, some eagles, a possum and one kangaroo.

2. Life in London. Jumbo was carefully nursed to health by his caretaker Matthew Scott – who would sleep in the enclosure with his charge, carefully lotioning his feet and providing nightly cocktails – and became the star of the London Zoo. Before long, he was touted as the “Children’s Giant Friend” – carrying dozens of children on his back for regular laps around the zoo grounds. Scott would occasionally go down to the Thames with Jumbo for a bath, which must have been an unusual sight indeed for folks out for a stroll in London.

3. So how did Barnum get Jumbo, if he was such a hit in London? Behind the scenes, the zoo was eager to sell: not only was Matthew Scott a high-maintenance human resources nightmare, the elephant was becoming increasingly hard to handle. A combination of anxiety, hormonal outbursts and possible nutritional deficiency gave Jumbo a fragile disposition, and he would often spend evenings tearing his pen to matchsticks in anger and frustration (he is usually shown with trimmed tusks because they broke off in a fit of destructive rage).

4. Wait, why “Jumbo?” No one knows for sure. Suggestions on the origin of Jumbo’s name range from the idea that it is a corruption of the Swahili word “jambo;” an allusion to “mumbo jumbo,” or simply a nonsense word. But his name is still used today to refer to anything impressively large, from stadium screens to voluminous slushy drinks.

5. Barnum brought him to the United States with a grand debut on Easter Sunday in 1882. A team of elephants and horses carried Jumbo up Broadway, and he was quickly put to work at Madison Square Garden as the star of the Greatest Show on Earth. For shows on the road, Scott and Jumbo rode together in “Jumbo’s Palace,” a custom rail car forty feet long, thirteen feet tall and eight wide. Unfortunately, Jumbo didn’t like train travel and during bumpy evenings would reach out with his trunk for Scott.

6. He quality-tested the then-new Brooklyn Bridge in 1884. Folks were nervous about the staying power of something so grand and ambitious, and even a year after its opening, there were plenty of folks who were too afraid to set foot on the bridge. And so P.T. Barnum announced that, on May 17, 1884, he would publicly assure New York of the bridge’s strength. Bright and early, the showman arranged for twenty-one elephants, seven camels and ten dromedaries to make their way up Broadway to the bridge. As crowds gathered street side and peeked out of upper-floor windows, the animals began a slow march across from Manhattan to Brooklyn. A child was heard to yell, “Hooray, there’s Jumbo!” and the excitement “spread like a financial crisis.”* Jumbo brought up the rear of the procession as it made its way to Brooklyn, flapping his ears at pretty girls who leaned out of their windows to catch a glimpse of his majesty. After marching across the bridge, the menagerie – a walking advertisement if ever there was one – dutifully headed for the Brooklyn fair grounds at which Barnum’s circus was to open the following Monday.

7. “Jumbo-mania” inspired a merchandising bonanza. The elephant’s name and likeness were used to sell everything from sheet music to sewing thread, candy to patent medicines (see the Castoria ad in the header image above, for a medicinal oil).

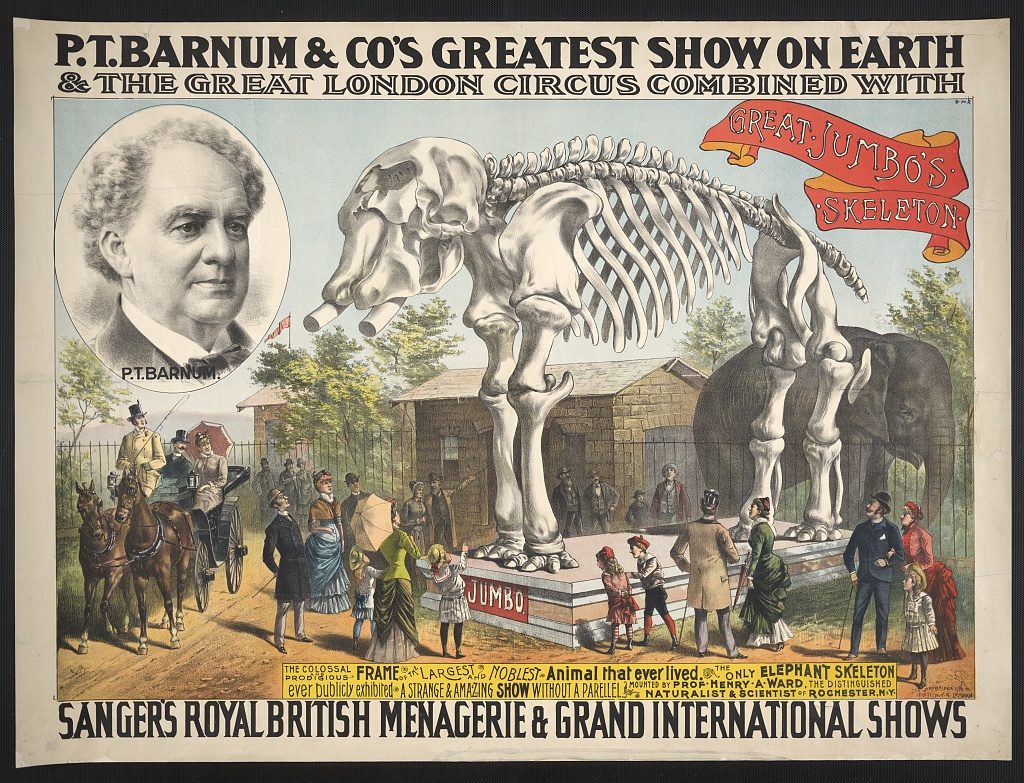

8. The “Double Jumbo.” Jumbo died in a horrible accident on September 15, 1885, when an unscheduled freight train collided with the elephant as he crossed the tracks in Ontario. Even this did not dull Barnum’s trademark promotional instincts, and he had the elephant’s hide and skeleton separately mounted so the “Double Jumbo” could go on tour even in death. The skeleton remains in the collection of the American Museum of Natural History in New York (see the handwritten accession record).

9. Go Jumbos! Fight! Win! As for the other half, Jumbo’s stuffed hide was donated to Tufts University, of which Barnum was an early benefactor. Jumbo – most of him, anyway – was lost in a fire in the 1970s when Barnum Hall went up in smoke. The university still has his tail, and a glass peanut butter jar containing a handful of his ashes, which sports teams are said to tap for good luck. Jumbo remains the college mascot.

10. What about Mrs. Jumbo? Even Dumbo’s mother Mrs. Jumbo has a real-life analog: the elephant Alice, who was (in a very large promotional stretch) referred to as Jumbo’s “widow.” After Jumbo’s untimely death, Barnum arranged to have Alice brought to the the United States from England, causing the New York Times to write in 1886: “My poor old Jumbo, your Alice weeps for you.”

Fun Facts:

People will tell you there was an elephant stampede on the Brooklyn Bridge. It’s a good story – and even a monument! – but, you know, there’s a sucker born…

(P.S.: Barnum didn’t say that, either.)

Additional Reading:

Paul Chambers, Jumbo: This Being the True Story of the Greatest Elephant in the World (2008)

* “Elephants Cross the Bridge,” New York Times, May 18, 1884

April Jones Prince & Francois Roca, Twenty-One Elephants and Still Standing (2005)