Have a drink with: Joseph Priestley

Chemist, radical theologian, likes bubbles.

Ask him about: favorite La Croix flavor?

Part of social life for well-to-do Europeans in the eighteenth century was to visit a spa town – someplace like Bath in England, or the town of Spa in Belgium – and “take the waters.” Not unlike a modern wellness retreat, at which you can sneak in some pool time or an Instagrammable view in addition to your yoga class or cleanse, these getaways generally rationalized a desire to rest up and relax with a regimen of health-focused activities centered on the various mineral springs. Not only did visitors bathe in springs and baths at popular wellness destinations, they also drank the water, which on account of its geothermal properties and mineral content was often sharply flavored and sometimes effervescent.

Put another way: seltzer may be super in right now, but don’t forget that it was the on-trend drink of summer 1767, too.

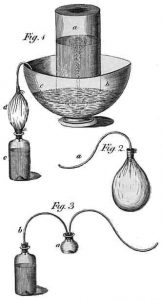

For this, you can thank Joseph Priestley, a chemist, philosopher and minister born in early 18th century England. Assigned to a parish in Leeds in 1767, Priestley discovered on moving to the area that his new home was next door to a local brewery, which gave him ample opportunity to use it as a lab for researching the properties of “fixed air,” or carbon dioxide. The brewery produced its beer in large vats, and as a natural byproduct of the fermentation process, a layer of yeast-produced carbon dioxide floated in the foot of space above the surface of the liquid. Priestley, curious, took a dish of water and set it up so it hung suspended within this gaseous layer. He let the dish sit overnight to see what might happen, and in the morning discovered that the previously flat water had absorbed enough carbon dioxide to change its taste and texture.

Further experimentation revealed that he could also infuse flat water with bubbles by sloshing it back and forth between two glasses while holding them within the gas layer, producing something that tasted pretty much like the sparkling water people traveled to fancy spa towns for. Modern chemist W.A. Campbell claims that these experiments were short-lived, since Priestley’s neighbors were only so patient with their next-door neighbor repeatedly dangling weird contaminants over perfectly good vats of beer, but the point had been made.

By the final years of the 18th century, there were a handful of commercial ventures making sparkling water, including a partnership involving Johann Jacob Schweppe, a Swiss watchmaker who figured out how to not only make but productively bottle the stuff. Schweppe expanded operations from Switzerland to England, and with the opening of a London factory became the forerunner of the modern Schweppes beverage brand.

Priestley continued to work on apparatus for infusing water with carbon dioxide, hoping that among other things maybe seltzer could prevent scurvy; but this was only one part of his larger scientific career. He experimented with various gases through his lifetime and clung to a far-fetched theory that claimed a mystery element called “phlogiston” was the reason that materials burned. In isolating what he claimed was de-phlogiston-ated air, Priestley actually discovered oxygen gas. You can’t win ‘em all.

(I bet he’d have liked pamplemousse.)

Fun Facts:

The Belgian town of Spa, popular for centuries for its mineral springs, is largely thought to be the reason we today call a spa a spa. Also, if you keep writing the word “spa” enough times it starts to look funny. Spa spa spa.

Know Your Bubbly Waters: “seltzer” is the term for carbonated water, while club soda has added minerals like sodium carbonate (a literal “soda”).

You had to be careful about, uh, natural flavors in 18th century seltzer: because Priestley’s eventual rig for making the stuff – as well as similar setups developed and used by other experimenters – used actual animal bladders to hold needed gases, there was the risk that you might end up with something that had rather too much of a “urinous taste.”*

Priestley’s surviving scientific fame is often colored by the fact that he held controversial religious and political and scientific views, and not just on the phlogiston thing – Priestley’s house was burned in a riot in 1791 because, as a separatist Christian, he was pro-French Revolution and anti-Church of England, and this pissed off his neighbors. He moved to Pennsylvania.

Additional Reading:

Sheila Marikar, “The Seltzer Bubble,” The New York Times, July 13, 2019

* W.A. Campbell, “Joseph Priestley’s Soda Water,” Endeavour, vol. 7, no.3 (1983)

David Henry Peacock, Joseph Priestley (1919)