Have a drink with: Glenn Miller

Pennsylvania six-five-thousand!

Ask him about: giving Sousa some swing

Chances are, if I say “Glenn Miller,” something like “Moonlight Serenade” floats into your mind on cottony clouds, the dreamy musical equivalent of a Vaseline filter; or maybe it’s the sharp, perky big-band swing of “In the Mood.” Point is, the phrase “early-morning scourge of stuffy Yale professors” is not high on the list of speedy free associations. But in 1943, that was exactly on the nose – and Glenn Miller was waking up sleepy Ivy League students. For America.

In the 1940s, Yale was not so much a college as a military training facility. Confronted with the job of simultaneously serving the nation and its own educational goals, Yale converted to war. The Army Air Force Technical Training School was established at Yale in January 1943, and in a month’s time the campus was overtaken by some three thousand cadets, officers and instructors (accounting for other service branches, Yale hosted as many as seven thousand soldiers). It was quickly apparent that music added needed color to the University as it faced wartime, and served a valuable purpose, too: radio had not been available on a large scale in World War I, and armed service branches quickly realized that radio broadcasts were ideal for promoting recruitment efforts and boosting public morale. Since New Haven was the nearest branch of the Technical Training Command to New York City and its national media infrastructure, Yale was selected as the site of the AAF’s East Coast radio unit.

The Army Air Force Technical Training Command Band under Glenn Miller was stationed at Yale for fifteen months during the Second World War, beginning in March of 1943. At the peak of his career Glenn Miller left his popular dance band to enlist, and as a captain in the Army Air Corps was asked to build and direct a music program to serve the military. Determined to bring the best enlisted musicians into his fold (indeed, many in civilian life had played with such greats as Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey), Miller deftly massaged regulations, and at one point was said to have more than a hundred musicians under his command.

Miller originally served as director of bands for the whole AAFTC, but his “baby” was the 418th Army Air Forces Band, his personal clutch of players stationed on the freshman quad in New Haven. The same band that would become famous worldwide for its victory broadcasts, war bond drives and overseas performances (and for giving staid military music an occasionally controversial dose of swing) was in 1943 to be seen around New Haven rehearsing and accompanying daily military activities, from meals in the Commons dining hall to exercises on the New Haven Green. A smiling blurb in the August 1943 Yale Alumni Magazine noted that “Mr. Tinker was forced to end his first lecture of the term early because the band came down College Street at 9:50 one morning playing a deafening arrangement of The Jersey Bounce.”

In the spring and early summer of 1943, Miller’s flagship 418th Band broadcast six shows live from Yale’s Woolsey Hall. These programs were intended as a proof of concept for national public relations broadcasts, and aired on Boston’s WEEI radio. The first test was broadcast on the evening of May 29, 1943, and by July it was clear that the program – “I Sustain the Wings,” after the division motto “Sustineo Alas” – was ready for a national stage. It was a tremendous hit.

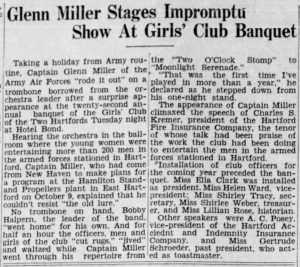

In addition to managing a far-flung network of military bands, Miller kept his own group rehearsed to sharp precision, and maintained a very busy calendar of engagements. Coverage from 1943 notes that Miller performed a war bond show at Hartford’s Bushnell Theater, advertised live on local radio, continued to play at cadet exercises, and even made some surprise personal appearances, including dropping into a local ladies’ club event to play for half an hour on a borrowed trombone:

Miller remained in New Haven until June 1944, at which time the unit was assigned to perform for troops serving overseas. Six months later, while flying between London and Paris, Miller’s plane was lost in the fog and never seen again:

On December 6, if you’re local to the New Haven area, you can (and should) go see a re-enactment of the Yale broadcasts, on the very same stage that the Miller band used for those handful of weeks in 1943. The Yale Bands will not only bring the Miller show back to life, they will – true to WWII holiday form – debut “Rosie’s Riveters Big Band,” an all-women’s band performing a 1940s holiday concert.

Fun Facts:

This is our 100th post! Thanks for reading and supporting Drinks With Dead People all these years.

In the late 1990s, local advocacy for Miller and his generally under-publicized time in Connecticut led to Glenn Miller receiving a memorial stone in New Haven’s Grove Street cemetery.

It wasn’t just radio: on July 28, 1943, Miller orchestrated a parade and rally at the Yale Bowl in support of the new USS Shangri-La aircraft carrier. Thirty thousand spectators watched as the Miller band marched in formation around the field, and Army jeeps drove amidst the musicians, carrying the rhythm section. The rally raised approximately $2.25 million in war bonds.

Wait: swing music, controversial? A particularly catty line of coverage in Time magazine in 1943 had the old guard clutching their pearls at Miller’s addition of some sizzle to military tradition. Wrote one Time reader: “I have just read with complete disgust…that Captain Glenn Miller has begun to ‘swing’ the age-old, magnificent marches of John Philip Sousa.” Another replied: “Captain Glenn Miller has the right idea swinging those Sousa marches. The tunes are marvelous but the way Army bands have played them in the past has made them sound like an old-fashioned victrola which needed to be wound up.”

Go ahead: experience the original Miller band in Sun Valley Serenade, a 1941 movie featuring Miller’s civilian band at the height of its fame; or time-travel forward with the Brian Setzer Orchestra’s far more recent re-tread of “In The Mood.”

Additional Reading:

Dennis M. Spragg, Glenn Miller Declassified (2017)

Geoffrey Butcher, Next To A Letter From Home: Major Glenn Miller’s Wartime Band (1986)

Edward F. Polic, The Glenn Miller Army Air Force Band: Sustineo Alas / I Sustain the Wings, vol.1 (1989)