Raise a glass to: Democracy

Vote! Vote! Vote!

Look. A lot of people are saying a lot of things about Election Day. The results may take too long. Is absentee balloting trustworthy? And what the hell is up with the Electoral College? It is all very stressful. But these questions are not new, and there are some historical precedents we can lean our tired selves on:

I mean, absentee ballots, though?

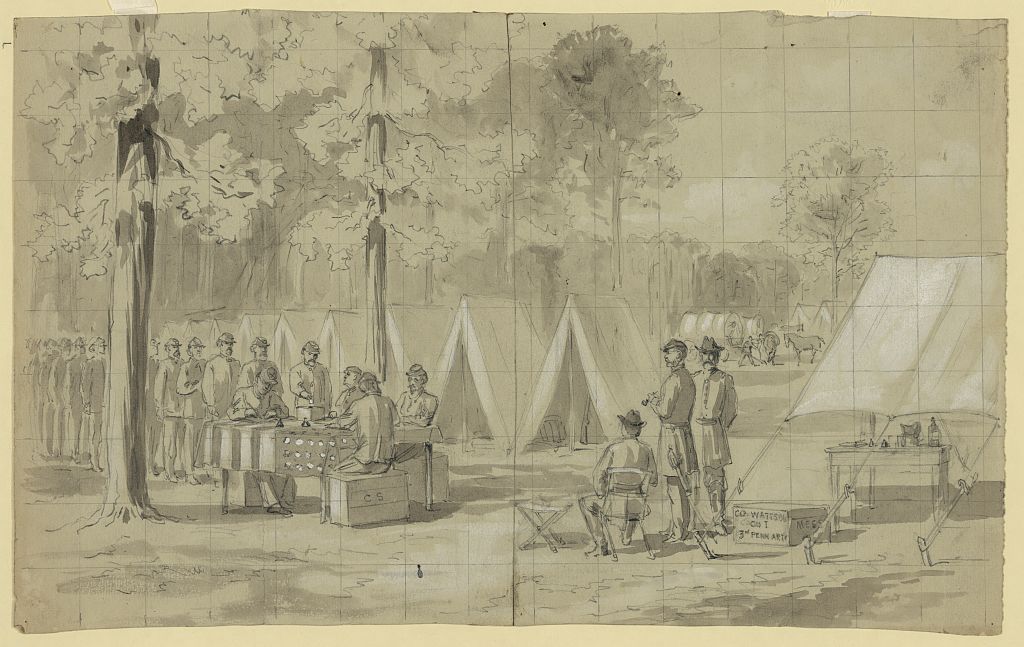

They’re common, safe, and have been in use for a long time – especially among American military personnel (the image above shows Pennsylvania soldiers voting during the Civil War).

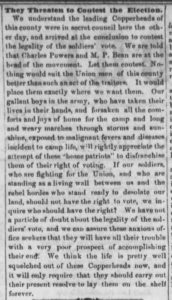

With so many men serving in the Civil War, soldier voting laws were passed across a number of states in the early 1860s, and they drew both praise and criticism. Opponents were mostly Southern sympathizers; in Ohio, local coverage noted that Copperheads (an anti-Lincoln contingent) didn’t like Union soldiers voting absentee, and intended to protest their votes as fraudulent (click to enlarge):

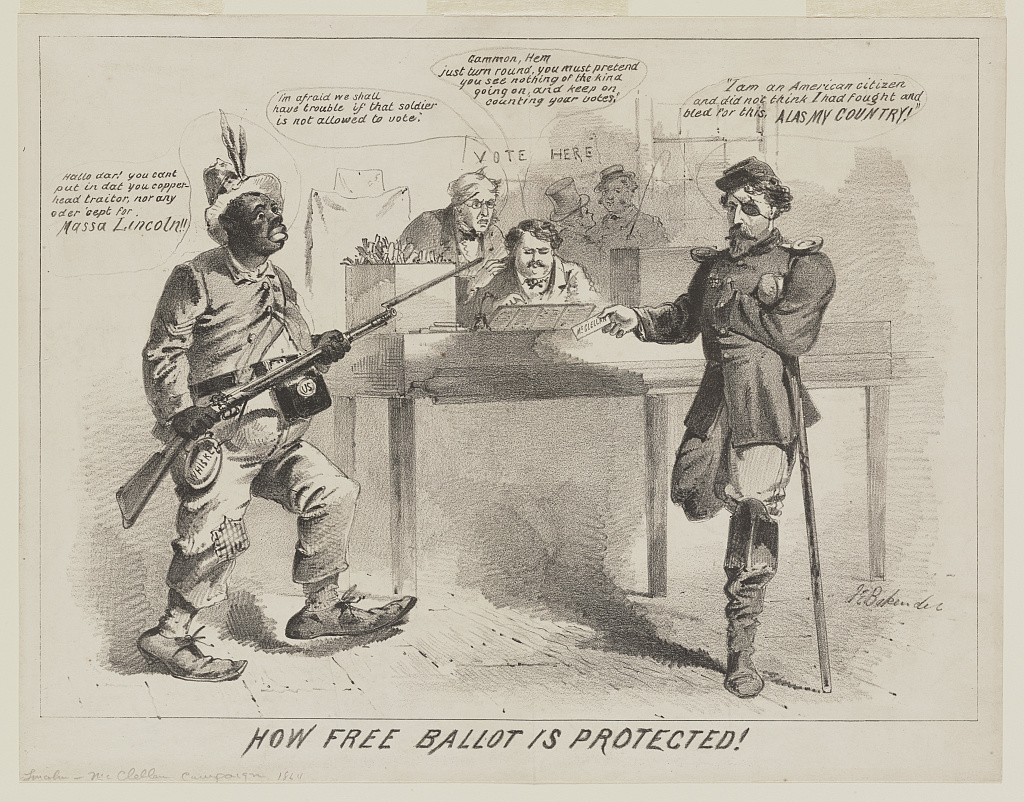

And an 1864 print made clear exactly what Civil War-era Democrats felt was at stake: entitled “How free ballot is protected,” the image shows a one-legged white soldier pining, “Alas my country!” while the town clerk nods at a Black caricature urging support for “Massa Lincoln” and says, “I’m afraid we shall have trouble if that soldier is not allowed to vote.”

Instant gratification?

For much of American history, you had to wait a little to get your voting results – sometimes, a very long while.

Early American elections were not a single-day affair but lasted weeks, since a 1792 law provided for a period of 34 days in which states could choose their electors. The election of 1824 ranged from October to early December, and dragged on further still when it became clear that no candidate had won an electoral majority and Congress had to sort the issue out by electing John Quincy Adams in February 1825.

For folks who lived in Utah during the 1860 presidential election, the Pony Express was still trickling bits of election data their way weeks after the November 6th election – the Mountaineer in Salt Lake City was publishing Pony Express results on a delay (news printed on the 14th of November had been telegraphed to St Joseph, Missouri, and left via Pony on the 8th). Abraham Lincoln, for his anxious part, benefited from the speed of telegraph reports, and had stayed up all of election night waiting for returns to come in, stationed in a nearby ice cream parlor housing sandwiches and coffee.

In that Ohio governor’s election, which was held October 13, 1863, the Fremont Weekly Journal noted that “Fourteen additional poll books, from as many different election places, have been received since the above were counted, but which will probably not be opened until the twelfth of November when the final count will be made.”

These things take time.

But the Electoral College.

Look, it’s not like we were ever really totally happy with it: according to the Congressional Research Service, there have been more than 750 proposals towards reform of the Electoral College throughout American history.

When do we vote, anyway?

In 1845, Congress passed a law that fixed the presidential election to its current early November status (in part because of that telegraph, so one state’s communicated results could not influence another’s over a scattershot 34 days). With characteristic verbal economy, that was: “The Tuesday next after the first Monday in the month of November of the year in which they are to be appointed.” Originally the law applied only to the electors choosing President and Vice President, but it was later extended to apply to Congressional elections.

I need fortification.

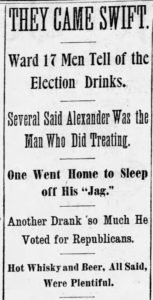

That’s fine, but you’ll have to buy your own: many states at times passed local laws prohibiting the sale or distribution of alcohol on Election Day, because it was not unheard of for party operatives to hand out free booze to either incentivize voters to vote a certain way, or to get them so blitzed they didn’t remember their candidates’ names.

Or, if booze isn’t your thing, take a page from my home state and bake yourself up a Connecticut Election Cake. According to State Historian Walt Woodward, “The idea of democracy itself—that in America the people chose their own rulers—was a sweet one, and the entire week surrounding the May election and inauguration of state officials was an extended period of pomp, circumstance, parades, and celebration. Crucial to every fete was an Election Cake.” Every household baked rum-soaked spice cake studded with raisins and frosting, in staggering quantities (we’re talking 20 pounds of flour at a go here), and shared slices liberally among friends, neighbors and passers-by.

Fun Facts:

Voting is good.

Additional Reading:

Smithsonian National Postal Museum, “Absentee voting in the Civil War”

Josiah Henry Benton, Voting in the Field: a forgotten chapter of the Civil War (1915)

Kevin Kosar et al, “The Conservative Case for Expanded Access to Absentee Ballots,” R Street Institute (2020)

Walt Woodward, “Sweet Democracy: The History of the Connecticut Election Cake,” Connecticut Explored (2017)