Have a drink with: Salvador Dalí

Girls, girls, girls. Plus lobsters.

Ask him about: But how do you make the giraffe explode?

The 1939-1940 World’s Fair was a tremendous attraction, drawing more than forty million visitors to New York over its two seasons to experience the “World of Tomorrow.” Built over 1200 acres on top of the site of a former ash dump in Queens, the sprawling fairground was an ode to progress and international modernity, featuring a number of attractions meant to bring people out of the emotional and economic slump of the Depression. There were technological pavilions showing off new wonders like Formica and television sets; a range of theatrical entertainments including Billy Rose’s all-swimming, all-dancing Aquacade and Gypsy Rose Lee in “The Streets of Paris;” celebrations of the 150th anniversary of George Washington’s inaugural; and, looming over it all, giant modernist ball and spire sculptures called the Trylon and Perisphere. President Franklin Roosevelt became the first president to appear on television with his broadcast introductory speech.

And if you looked at this prewar proto-Epcot spectacle and said, well, this is all well and good, but it is missing one major component, and that component is a whole lot of fish, rest assured: Salvador Dalí to the rescue.

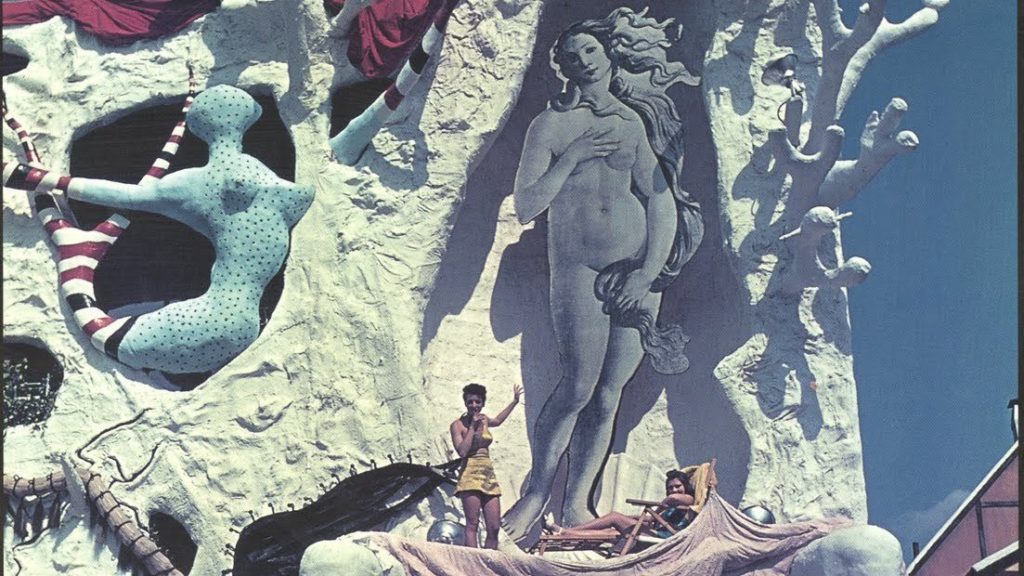

Because, yes, the World’s Fair organizers decided it was a good idea to invite the surrealist painter and ocelot dad Salvador Dalí to set up his very own theatrical attraction on the fairgrounds, as a means to introduce Americans to surrealism outside the gallery world. The resulting performance, entitled the Dream of Venus, stood in decided contrast to the otherwise sensible and chrome-plated World’s Fair design, and took place in an utterly bananapants pavilion that looked like sentient stucco had decided to leave the building mid-construction.

From the outside, the Dream of Venus made Terry Gilliam look sober and staid: the building was adorned with stucco branches, a giant Botticelli Venus, and various sculptures that call to mind anglerfish, or the sandworms from Beetlejuice. Visitors saw classical Renaissance vignettes through holes in the facade, and walked inside through an entrance flanked by a pair of striped legs. Inside, bathed in colored light, women in bikinis and bare-breasted swimsuits (some of them with strategically placed lobsters, as was Dalí’s fashion; link NSFW) swam through a weird concrete grotto, typed on underwater typewriters, and adored a reclining nude Venus. A live-action war between classical and modern art by way of burlesque, the attraction contained melting clocks, piano keyboards, a bandaged cow, birdcages, and more lobsters.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Dalí and the Fair organizers had some back-and-forth about the artist’s vision before it was brought to life in Queens. Dalí and a gallerist friend had come up with a long list of possible names for the exhibition, including (to name just a few): Dali’s Nude Aquarium, No Nudes Are Good Nudes, Swimmin’ Women, and See! Sea! Si! Dalí! In the end, Dalí’s Dream of Venus was the acceptably safe choice.

The content, too, had to be tamed down from the drawing board to the stage: in a letter to Luis Buñuel, Dalí described his vision for the show as “a Surrealist pavilion for the World’s Fair with genuine explosive giraffes.” This, understandably, was difficult to achieve.

As an ostensible concession, Dalí wanted his aquatic theme to include fish heads. Lots of fish heads. A fish’s head on Botticelli’s Venus, and fish heads on many of his partially-nude swimmers. The Fair’s organizers, by now rubbing their temples, urged him to maybe stick to mermaids. An enraged Dalí, in response, wrote and air-dropped on New York a manifesto called the Declaration of the Independence of the Imagination and the Rights of Man to His Own Madness, in which he argued that avant-garde art was necessary to keep creative integrity and to fight the banal oppression of capitalist society. Those are my words. His were, and I quote, “It is man’s right to love women with the ecstatic heads of fish.”

Dalí’s pavilion opened, albeit late (a press release blamed “the complexity of the subconscious”) and though the show continued to draw crowds throughout the Fair, it was more ambitious than could be sustained. (One reviewer noted that “The original was startlingly staged, shockingly costumed, bluntly sexy, and ended the season with a $50,000 deficit.”) In its second season, after Dalí himself had moved on to other pursuits, it was brought into the feel of a more conventional burlesque and renamed 20,000 Legs Under the Sea.

Fun Facts:

Video of the Dream of Venus can be seen here, starting at about the 40 second mark.

Dalí’s pavilion was demolished after the Fair in 1940. The Trylon and Perisphere, the iconic modernist symbols of the World’s Fair, were also demolished, and used to make World War II arms.

The World’s Fair was bombed in June 1940, and the case is still unsolved.

Another of the amazing developments hosted at the Fair: an early video gaming machine called the Nimatron, presented by Westinghouse at its technology pavilion.

Additional Reading:

Salvador Dalí, Declaration of the independence of imagination and the rights of man to his own madness (1939)

Riccardo Venturi, “Into the abyss. On Salvador Dali’s Dream of Venus,” in Botticelli Past and Present (2019)