Have a drink of: Nice Cold 17th Century Beer

Less filling; tastes great.

Ask your friends: to buy you a round.

In 1662 Charles II gave his charter to the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge (the “Royal Society,” for short). A hybrid of a gentleman’s club, an entrepreneurial incubator, a maker faire and a science journal, the Royal Society was prolifically dedicated to the idea – famously explained by Adam Savage – that the only difference between screwing around and science is writing it down.

In their own justifiably proud words: “We published Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica, and Benjamin Franklin’s kite experiment demonstrating the electrical nature of lightning. We backed James Cook’s journey to Tahiti, reaching Australia and New Zealand, to track the Transit of Venus. We published the first report in English of inoculation against disease, approved Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine, documented the eruption of Krakatoa and published Chadwick’s detection of the neutron that would lead to the unleashing of the atom.”

And let’s not forget: they made sure 17th century England could have cold beer in summertime.

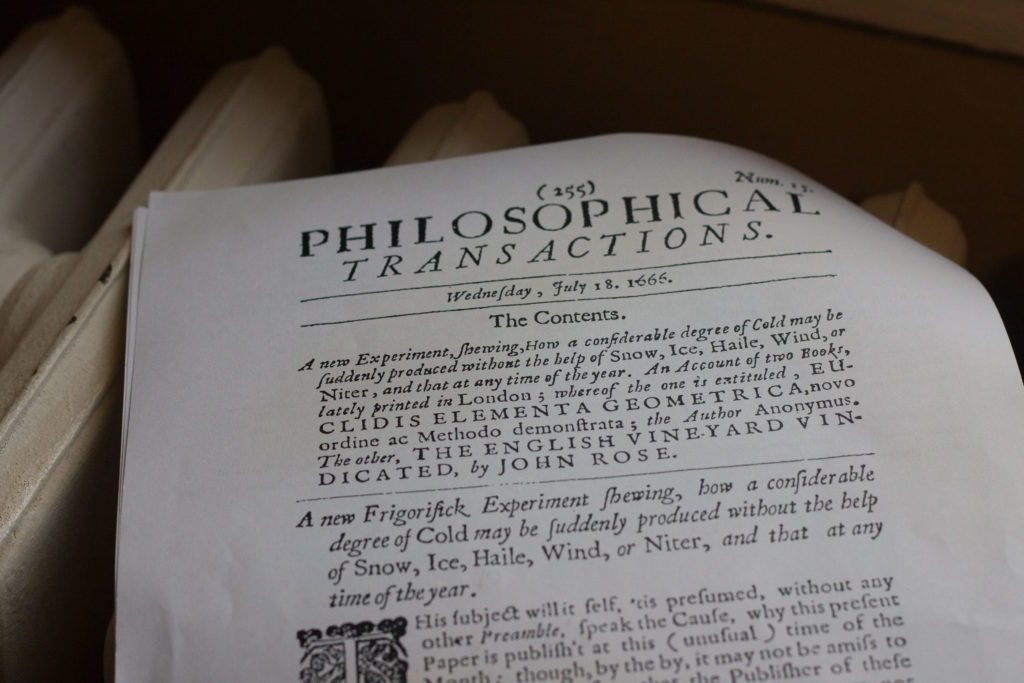

In a July 1666 issue of Philosophical Transactions, the Royal Society’s print edition and the “world’s first science journal,” an anonymous author described what he’d been up to in the backyard: “A new Frigorifick Experiment shewing, how a considerable degree of Cold may be suddenly produced without the help of Snow, Ice, Haile, Wind or Niter [potassium nitrate], and that at any time of the year.”

Not a bad thing to know on a no-doubt hot summer Wednesday:

“…yet the Weather having been of late very hot, and threatning to continue so, I presume, that to give you here in compliance with your Curiosity an Account of the Main and Practical part of the Experiment, may enable you to gratify not only the Curious among your Friends, but those of the Delicate, that are content to purchase a Coolness of Drinks at a somewhat chargeable rate.”

Bartending 101: amuse your friends, sell some drinks!

The experiment utilizes “sal ammoniack,” known in modern chemistry as ammonium chloride, and our scientist sets out a simple recipe: one pound of powdered ammonium chloride and about three pints of water – combined quickly for an intense chill, or mixed gradually for a longer-lasting effect. Just stir it up with a “stick or whalebone,” and satisfy yourself: the mix is cold to the touch and produces “little Drops of Water” on the side of a metallic mixing bowl. And, to the point:

“To cool Drinks with this Mixture, you may put them in thin Glasses, the thinner the better.”

An experimental mindset was table stakes for this particular community: the author eagerly tries different ingredient ratios, measures the mixture’s chilling effect with a weather glass, examines condensation and wonders about how to cut down on the cost of sal ammoniack.

“And thus much may suffice for this time concerning our Frigorifick Experiment,” he writes, “which I scarce doubt but the Cartesians will lay hold on as very favourable to some of their Tenents…”

I drink, therefore I am?

Fun Facts:

Frigorific mixtures, in science terms, are mixtures that produce an equilibrium temperature new and independent of the temperature of the individual component ingredients. Historically this has come in handy for things like calibrating thermometers or salting icy roads. This is not only sound science, but the sort that’s fun and safe to try at home.

There are other ways to get your beer cold, quick.

One of the coolest things about science in the 17th century is how much people loved to talk about it. The “virtuosi,” or amateur scientists of the era, enjoyed not only the escapism of getting together to talk about experimentation, but the process of gathering and communicating their data in print form. This had the effect of creating a genuine, active “social media” community – historian Elizabeth Yale (hi Beth!) notes that, thanks to correspondence and devotion to written records, readers “gained knowledge that made them neighbors to one another, though they might live at opposite ends of the island.”*

She calls the Royal Society ultimately an “institution devoted to making conversation productive,” and argues that the act of writing – as the result of research, correspondence, or plain note-taking – was part of a larger effort to give 17th century Britain an identity and a legacy, to speak the nation into being.

The Royal Society not only still exists (and publishes), they’re on Twitter. Check out a cool timeline of the group’s history at their website.

Additional Reading:

Philosophical Transactions, Wednesday, July 18, 1666 (this and other issues available via JSTOR)

* Elizabeth Yale, Sociable Knowledge: Natural History & the Nation in Early Modern Britain (see esp. Chapter 3)

Scientific American, Why Do We Put Salt on Icy Sidewalks In the Winter?

Dorothy Stimson, Amateurs of Science in 17th Century England, Isis, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Nov. 1939)