Have a drink with: Bruno Schulz

Writer, artist, cultural property puzzle, cult superstar

Ask him about: making hipsters’ heads explode.

My husband recently bought a bag from a company whose gleeful tagline was, “They’ll fight over it when you’re dead.” If post-mortem squabbles are really how you know you’ve hit the big time, Bruno Schulz is fist-pumping his way through the hereafter.

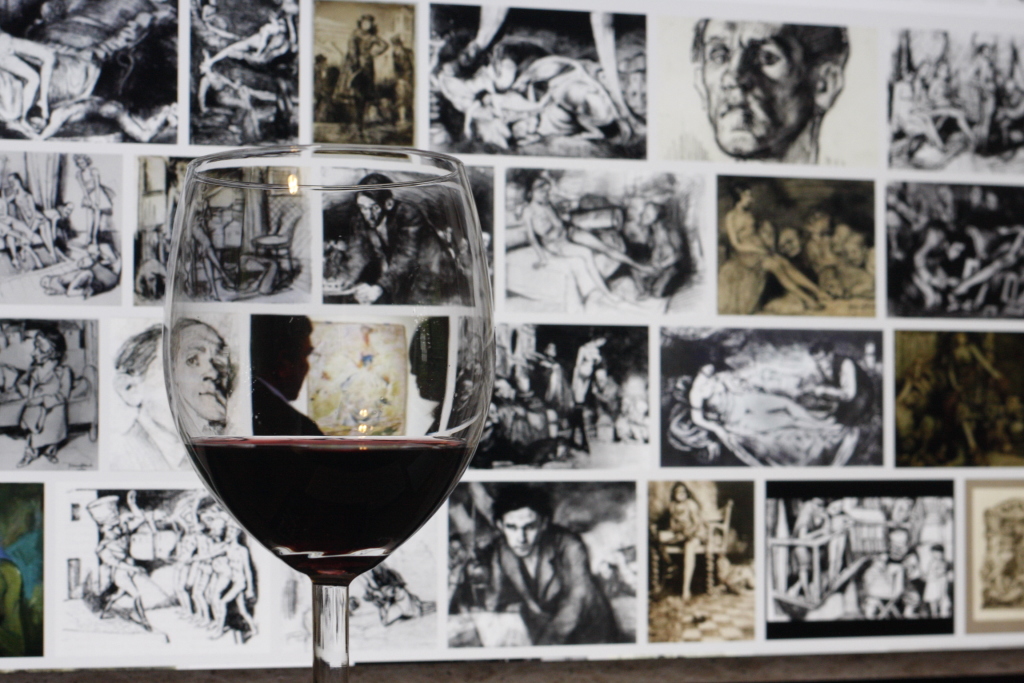

A prolific author and artist, Schulz is perhaps best known for his two volumes of short stories, The Street of Crocodiles (also sometimes known as Cinnamon Shops) and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass. Schulz lived in the city of Drohobycz – then part of Poland, now Ukranian – for most of his life, working as a drawing teacher and publishing works which tended towards the erotic and the grotesque. His art and writing were bold, unsentimental and yet wildly fantastical; Schulz was too grounded to be a surrealist, too oddball for mainstream, talented enough to be thoroughly disarming.

Schulz knew German as well as Polish, and as a Jew warranted attention by the Nazis in Poland. He was for a time protected as a skilled worker in Drohobycz by Felix Landau, a Gestapo officer who had him paint images and murals; but another Nazi officer, in petty retaliation against Landau, shot and killed Schulz in the street in November of 1942. Death, war and the vagaries of record-keeping mean that there’s a lot about Bruno Schulz we still don’t know – uncertain wishes, a mysterious lost novel – which means he is both confounding and incredibly alluring, particularly for creative seekers (a Guardian columnist noted that “more has been written about him than he ever wrote himself.”)

Schulz’s last works, murals of Grimm fairy tales painted in a children’s nursery on Landau’s order, were discovered under the walls of a local residence by documentary filmmaker Benjamin Geissler in 2001. Portions of the work were subsequently revealed by Polish conservators. In May of that year, representatives of the Israel-based Holocaust museum known as Yad Vashem traveled to Drohobycz to examine the works, and removed the exposed portions of the artwork from the wall for transport back to Israel. The obscured remainder of the piece was left behind. After the removal and Polish outcry alleging shady export, the Ukrainian government announced that the murals were to be considered a gift to the Israelis.

One of the loudest arguments over the Schulz murals was carried out in the pages of the New York Review of Books. American scholars of Central Europe got involved, university professors and museum professionals argued on Yad Vashem’s behalf, everyone was highly inflamed; in short, it was a good old-fashioned academic smackdown. On the one hand folks argued that Yad Vashem’s statement of moral right to the Schulz murals was evidence of a “new wave of predatory collecting,” a patent insult to the native people of Central Europe and their long history of cultural achievement and pluralism.

On the other, scholars claimed that Schulz was little remembered in his hometown, which anyway didn’t have sufficient resources to preserve his legacy, and that in aiding Yad Vashem, the mayor of Drohobych was elevating Schulz’s memory as part of the larger, necessary Holocaust narrative.

If nothing else, the debate highlighted one of the most frustrating, most human elements of cultural property disputes: that, in the end, uncertainty drives most people bonkers. In the end, everyone arguing over the Schulz murals really just wanted the group to agree on a label, to find SOMETHING about Bruno Schulz which told them what friggin’ drawer of the card catalog to use, for Pete’s sake.

There is a basic importance to humans of defining and sustaining associations that portray our legacy. The opportunity for group solidarity in any form gives rise to very passionate responses, as anyone who has worn full body paint to a professional sports event or attended a Phish show — or forty-seven consecutive Phish shows, as the case may be — can no doubt attest. And if culture is a self-contained universe for members of the group, a means of seeking significance and coherence in life, it follows that an individual draws identity from his or her culture and is shaped by its attitudes, traditions, practices and art forms. In short: people make stuff. The particular stuff they choose to make and to value has a lot to do with the company they keep. And when more than one group of people wants to lay claim to a particular thing and the story it tells, things can get emotional, quickly.

As an example, think of the long-running dispute over the Parthenon (aka Elgin) Marbles: one side argues that the world at large is enriched by being able to view these sculptures at the British Museum, another passionately claims that Greece’s heritage is irretrievably damaged when its cultural heart is kept abroad.

So how do people begin to weigh the preservation of a historical and cultural record, or the restitution of old injustices, against the possessory and pride interests of linked groups?

Like most cultural property squabbles, the answer in Schulz’ case is, clearly and unequivocally: it depends. It’s hard enough to even begin to focus your attention in Schulz’ case. Consider the many factors that emerge in even my thirty-second biography: Schulz lived in what at the time was Polish territory but which less than a century later is part of a wholly different nation. He wasn’t a single-career man: as an artist, writer and critic he continues to draw admirers in each of those creative fields. Linguistically, we’re all over the place: while Schulz self-identified as a Jew, he did not speak Yiddish; he knew German but for the most part chose to write in Polish. Faith, nationality and trade provide no objective answer in the matter of the murals, and indeed this tension was completely evident in the fact that Polish authorities, the Ukrainian government and Yad Vashem were consistently at each other’s throats over the matter.

Benjamin Paloff notes in his profile of the Schulz dispute that:

Increasingly, Schulz is regarded as a kind of cultural bridge: Poles see him as entirely Polish and entirely Jewish at the same time, making him both mysteriously alien and wholly native, an enticingly exotic member of their own family. For this reason, Schulz has lately been leaving a bitter taste in the mouths of some of his Polish admirers, who are now being forced to question whether he was theirs in the first place.

Having spent a fair amount of time arguing over everything from the nature of Schulz’ artwork to the ability of the then-current building owner to provide meaningful consent to remove the artwork, in early 2008 the parties reached a settlement. An announcement was made via press release that the Schulz murals would be recognized as “the property and cultural wealth of Ukraine, and will be on temporary loan at Yad Vashem for 20 years, after which the loan will be automatically renewed every five years. Yad Vashem wrote in its press release: “The conditions under which the murals were created, by the sole wish of the Nazi perpetrator and under his direct command – that is, forced labor – make them Holocaust artifacts.” But is it that easy?

Fist-pump for Bruno.

Fun facts:

There are references to Schulz in a lot of popular film and fiction, and he’s a particular favorite of surrealists and fantasists. The Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass was cult-famous in the mid-1980’s thanks to an acclaimed animated short film by the Brothers Quay. The short was cited by director Terry Gilliam on his top ten list of animated films.

Schulz is sometimes called “the Polish Kafka” for his menacing imagination, and, let’s face it, for having written a story in which he describes one of the characters having turned into a crab.

This short film includes comments from Benjamin Geissler, the filmmaker who found the hidden murals, and talks with Jonathan Safran Foer about his project Tree of Codes, made by cutting passages into and out of the Crocodiles manuscript – writing as sculpture, an exercise in reduction (around 21:00).

Check out: http://www.brunoschulzart.org and http://brunoschulz.eu/en to see some of Schulz’ art.

Cultural property disputes are fascinating, heated, and rarely easy. We live in a pluralist world that is only continuing to globalize and hybridize. Questions of origin and identity are rarely as open and shut as they may have seemed in centuries past, and even then they probably weren’t as easy as all that. Do you want to read a dense article about the philosophy of cultural property disputes? No, you want to know what George Clooney thinks about the Parthenon Marbles.

Additional reading:

NYT: Behind Fairy Tale Drawings, Walls Talk of Unspeakable Cruelty

New Yorker: The Lost – Searching for Bruno Schulz

Benjamin Paloff, Who Owns Bruno Schulz?, Boston Review (Dec 2004-Jan 2005)

For an excellent biography of Schulz, translated from the Polish edition, check out Jerzy Ficowski’s Regions of the Great Heresy: A Biographical Portrait of Bruno Schulz (2002).