Have a drink with: Akhenaten

Pharaoh, gender-bender, sun-worshiper, innovator

Ask him about: Starting your own religion in five easy steps

It’s amazing that so much interest persists in the ancient Egyptian ruler Akhenaten, a king about whom precious little is clear: no one knows when he was born or when he died, why he made the sweeping theological and societal changes that caused many scholars to call him the world’s first monotheist, or even who his successors were.

Still, it isn’t hard to see why the story’s a sticky one, and not least because company loves mystery. John Ray, writing in History Today, tossed off just a few of the speculations over which history has loved to ponder Akhenaten: “the ingredients are rich: a tormented visionary, a misunderstood poet, a visual artist of genius whose mission went unheeded, the apostle of domestic virtue, an incestuous child-abuser, a political disaster, an insane bisexual pope or ayatollah suffering from pathological endocrine disorder, a man out of his time.”

If Egyptian rulers were musicians, this guy is Gaga in a meat dress.

Akhenaten began life as Amunhotep IV, son of the pharaoh who built the Colosssi of Memnon. While he kept up the usual trappings of rule at first – working in Thebes, undertaking new temple building projects – it soon became clear that the young king had a distinct agenda focused not on historically prominent deities Amun and Re, but on the sun disk – the Aten. The king began to downplay historical modes of worship and minimized the role and reach of the priesthood – not a way to make friends in a royal city built on order and tradition.

Surviving records mention that a “bad thing” happened four or so years into the reign of Amunhotep IV, and while we have no idea what so offended the king, he did not take it sitting down.

The king adopted a new name – Akhenaten, or “one who is effective for the Aten,” left the traditional Theban cities and set up a new, distant capital city he named Akhetaten (now Amarna). The name meant “horizon of the Aten,” in perhaps literal reference to the way the sun rose over the mountains – a hieroglyph written in daily physical action.

Eventually Akhenaten did away with Amun altogether, closing temples and hacking the old god’s name from walls and carvings – a particularly outrageous act to Egyptians, who believed that to destroy a name was to extinguish that person in eternal time.

Now, when someone says “ancient Egypt” to you, no doubt a very particular aesthetic springs to mind, oft-parodied and very easy to imagine in shorthand thanks to mummy movies and the Bangles. Hieroglyphs, brains hooked out through the nose, gods with animal heads, way-oh-way-oh-oooh-way-oh…. (I’m not saying it’s right, but you can certainly identify it from fifty yards, which is the important part.)

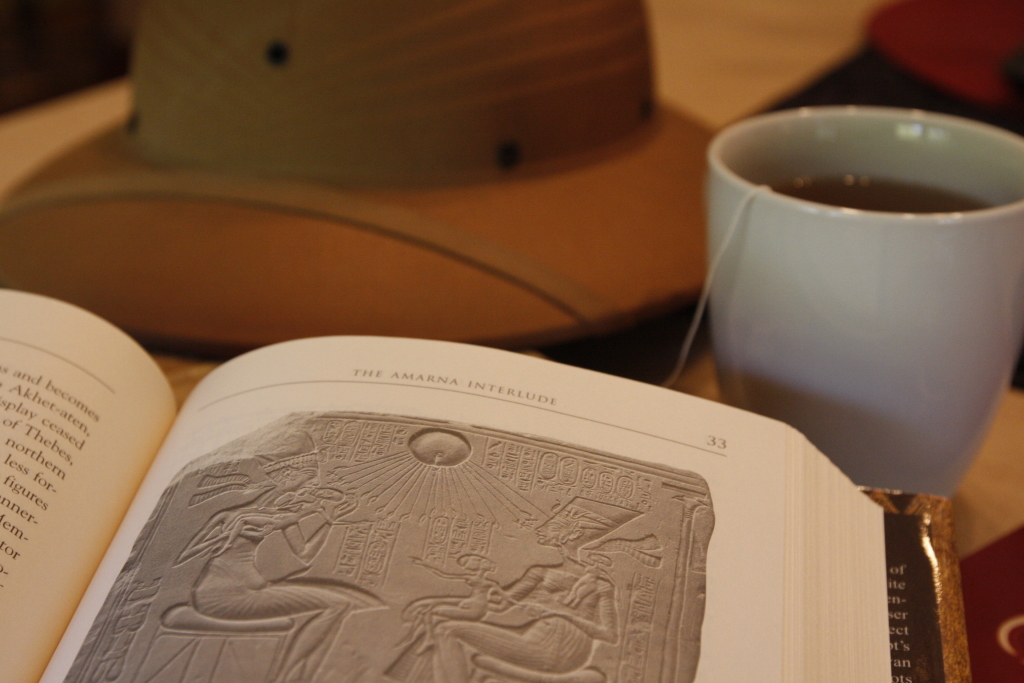

Amarna took this common, centuries-refined Egyptian visual language, and pulled it like taffy. Art suddenly became more angular, more stylized, exaggerated and yet in some ways more real (to wit: pot-bellies). Akhenaten himself was typically portrayed in an overwhelmingly feminine mode: curvy thighs and hips, womanly breasts and elegant facial features.

Moreover, the panoply of animal-headed gods was replaced with one icon: a sun disk reaching its many hands to earth, where the king was now venerated as society’s sole link to the divine Aten.

It wasn’t just art and dogma that changed, either: Akhenaten centralized power and resources to himself in Amarna, giving an increased police presence control over many jobs that had once been done by priests (things like tax collection and land management). So your average Egyptian definitely noticed things were different.

So disruptive is Akhenaten to the prevailing narrative of ancient Egypt that he’s not often discussed in moderate language. The man has been called a heretic king, a proto-Christian, a megalomaniac, or my favorite: “a butt-head.”

Unsurprisingly there are lots of suggestions for why Akhenaten made such sweeping changes to Egyptian society, and why those changes touched infrastructure, art, religion and real estate. Many are compelling and none are conclusive:

Some people will tell you Akhenaten was a revolutionary reformer, cleaning house of an entrenched corrupt priesthood. It’s possible, but that explains structural and political change more than it does the committed artistic and theological shift.

Others claim that Amarna art wasn’t a stylistic decision but the accurate depiction of an egomaniac king who was deformed by illness or genetic disorder. Also possible, but some scholars have pointed out that “disorders that would cause the deformations evident in Amarna art also result in sterility, and Akhenaten is known to have fathered at least six daughters and probably a son.” *

Then there’s the Trump Theory, or: It’s Good to Be King. Let’s not rule out the possibility that Akhenaten was, in the end, simply an eccentric narcissist given a whole lot of power. The Aten was the primary deity, but the royal family were his representatives on earth, and if the goal is to merge the king and the divine in aspect, then you can start to see why Akhenaten really was less a monotheist than someone who had a particularly high opinion of himself. Here’s why.

The Egyptians believed that the world was created from formless, dark waters containing the potential for all creation, a state of ultimate potential and ultimate nothingness called Nun. When a mound-shaped island of creation came out of the water and Nun started to differentiate itself, pairs emerged: light and dark, chaos and order, male and female. Proliferation of deities and stories proceeded from there. Ma’at (order) and Isfet (chaos) were especially important concepts – most Egyptian religious practice, and most of what any king did, was aimed at keeping the universe orderly and on its tracks. Religion wasn’t a set of distant stories, it was a daily participatory practice.

In venerating the Aten and elevating himself as its liaison, Akhenaten basically hit the cosmic rewind button and decided to think of himself and his wife Nefertiti as the first products of that squishy generative time at the beginning of everything. So, since he precedes all other gods, it isn’t so much that Akhenaten believed in a single god as that he declared that none beside himself had yet come into being.

In the “pre-creation” era, and thinking of himself as a powerful cosmic force, this may be an explanation for why Akhenaten portrays himself as androgynous: he possesses all qualities of life and creation, including feminine fertility.

It isn’t certain when Akhenaten died, nor where he was ultimately buried (there is argument over the Luxor tomb KV55 in the Valley of the Kings), but kick the bucket he and his cultural experiment eventually did. Not that death lent much clarity right away: the intermediate rulers over the next few years are unknown past speculation, including suggestions of a female pharaoh, whether Nefertiti or a daughter. References to Nefertiti in art and writing disappear around year 14 of the king’s rule, and it is unclear whether she predeceased him or went under an alias.

The famous boy king Tutankhamun assumed power four years later and eventually began to restore the old theological order, moving back to Thebes and paying honor to Amun. Amarna was, over time, dismantled and abandoned, and references to Akhenaten were removed.

But we still can’t stop looking at photos of the meat dress.

Fun facts:

The 3,400 year-old bust of Akhenaten’s wife Nefertiti currently residing in Berlin’s Neues Museum is as close as artifacts get to celebrity status in global culture, and this isn’t terribly surprising. The sculpture is uncommonly beautiful, impressively old, depicts an elegant and ostensibly powerful female royal figure, and retains much of its original paint job. Thanks to these facts and the bust’s notoriety and beauty, Nefertiti is now mythologized as an ancient celebrity figure — aloof, mysterious, commanding. The bust was first put on display in 1923 in Berlin, and has been the subject of oohs and aahs, not to mention arguments about ownership, ever since.

Sigmund Freud thought that Moses was not in fact a Jewish figure, but was a descendant of Ancient Egypt, with particular attention to Akhenaten and his alleged monotheism. See: Moses & Monotheism.

My favorite Egyptian religion story, speaking to the importance of the solar cycle in religious practice: in one line of thinking, Egyptians envisioned the sun as the cat deity Bastet, calm and lovely, until changing seasons made the days shorter. The sun’s “departure” meant that Bastet had become angry, transformed into the lioness Sekhmet and traveled to distant lands where she could go on a spree eating foreigners. When longer days came back around, the populace would throw a giant, government-subsidized party to celebrate the goddess’ return and pacify the lioness; dyeing gallons and gallons of beer blood red, crowds would drink themselves silly as proxy for Sekhmet, who would become Bastet again once she was sated, drunk and happy. For ancient Egyptians, their tax dollars at work.

By the way, beer was a big deal in Egyptian society, part of ritual offerings and daily rations alike. Brewer Dogfish Head recently tried to recreate an Egyptian historical recipe, calling the result “Ta Henket” after the transliterated hierogylphs for “bread and beer.”

Amarna was located across the Nile from Hermopolis, the primal home of the eight gods called the “ogdoad.” There was a north city and north palace, then the central city with large and small Aten temples to the south. Akhenaten’s work commute consisted of a chariot ride from the north city to the south; the north palace belonged to his daughter, whose emergence to meet the chariot was an analog of the north star’s rising. The king would take care of state business, etc. in the south at the central city and then return home to the north in a mimicry of the solar new year’s journey (and every day is new year’s, since he’d returned to the beginning of time).

King Tut was born “Tutankaten,” but for obvious reasons changed his primary name to “Tutankhamun” to distance himself from the Amarna unpleasantness. For equally obvious reasons, please enjoy this video of Steve Martin.

Additional reading:

John Ray, “Akhenaten: Ancient Egypt’s Prodigal Son?” History Today 40 (1990) 30.

Amarna hair extensions!

* John Darnell and Colleen Manassa, Tutankhamun’s Armies

Geraldine Pinch, Egyptian Myth: A Very Short Introduction

Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt

Rick Gore, Pharaohs of the Sun, National Geographic online, April 2001

Dominic Montserrat, Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt