Have a drink with: New Haven Puritans

Judge swung his fist down, plunk plunk…

Ask them about: Anything but Quakers.

It’s election season, which means we are faced with ample opportunity to confront our worst tendencies and unresolved problems as a society, along with the inevitable call to harken back to a better, simpler, more moral time in American history.

Just so we’re clear, though, that time was not the 17th century.

Consider The Case of the Piglet’s Paternity, a fascinating collection of thirty-three cases heard before the Puritan courts of the 17th century New Haven Colony and superbly edited by Connecticut superior court judge Jon Blue. We can learn a few things from this book:

- Do not let a few instances of good justice wallpaper over a majority approach that marginalizes citizens and preserves a fear-based status quo.

- Don’t serve sailors booze by the quart.

On a summer Saturday in 1648, a group of seven sailors met up in New Haven and headed to the home of Robert Bassett to order some after-work drinks. Keeping in mind that local law required a license to sell “any sort of wine or strong liquors by retail, namely by pottles, quarts, pints or the like” (a “pottle” is a two quart measure), Bassett told his guests not to worry: he could serve them, all right, so long as they were ok taking things in a three-quart serving. They were fine with this, and Bassett thought they were such nice guys he pulled them an extra three.

And since, in the immortal words of the great historian Elton John, Saturday night’s alright for fighting, on August 1, 1648, the General Court of New Haven Colony had to officially ask: what DO you do with drunken sailors?

The case of the sailors (who were summarily fined and warned “against all future disorder,” as well as against interpreting laws with three-quart liberalism) is just one of many recorded in The Case of the Piglet’s Paternity.

Judge Blue writes:

“Persons of all descriptions appeared before the New Haven courts and had intimate portraits of their lives recorded for posterity. Reading carefully, we learn that the New Haven Colony, regardless of its official theology, was far from a peaceful assembly of religious folk living quiet lives of biblical virtue. However strict the colony’s political and religious rule, turmoil seethed beneath the surface. Church members dissented from the colony’s political and religious rule. Women rebelled from the church and its teachings. The colony’s young people (no surprise to us!) strayed from its official teachings and had premarital sex. More disturbingly, the colony’s economy was built on the labor of women, servants, and children.”*

In one case, a woman who discovers and proves her long-absent husband was living a double life in Ireland with a second wife received a divorce and freedom to remarry – a remarkable, pragmatic kindness to a woman in such a restrictive society. And in commercial matters, we find the court was careful and even creative in coming to fair resolution of disputes: Blue describes cases in which the court awards damages to a man injured by a poorly-kept gun that exploded when fired; goes after a shoemaker who “wrongs the country” by making shoddy shoes with bad leather; and adjudicates a complex shipping dispute.

But when white men and their commercial interests were not involved, there was no fault tolerance: we see that these Puritans are normal people subjected to abnormal pressure and moral judgment (it’s fair to note here that nonconformist Puritans left England not so much because they loved the idea of tolerance as that they really wanted some elbow room for their own orthodoxy).

The few instances of objectivity and compassion only drive home the point that the court was, overall, pretty awful.

In the title case, the community concluded from the stillbirth of a one-eyed piglet that the shifty one-eyed guy in town must have screwed a pig – and went so far as to arrest the man, coerce a confession from him in prison, and execute not only the man but the pig as well. We read about a woman who was the victim of sexual harassment and was punished physically while her abuser skipped town; about children who essentially served as indentured servants and who were brought to court for frustrated acts of vandalism against their abusive employers; and generally terrible treatment of Native Americans and Quakers.

It begs the question: how do we create justice for ourselves? As much as overall norms move forward, are we only as good as our lousiest rulings? And we may no longer raise a hue and cry over visiting Quakers, but when we institutionally treat people of color with the narrowest of assumptions and corporations with the broadest ones, well, it’s still enough to make you want to drink by the quart.

Fun Facts:

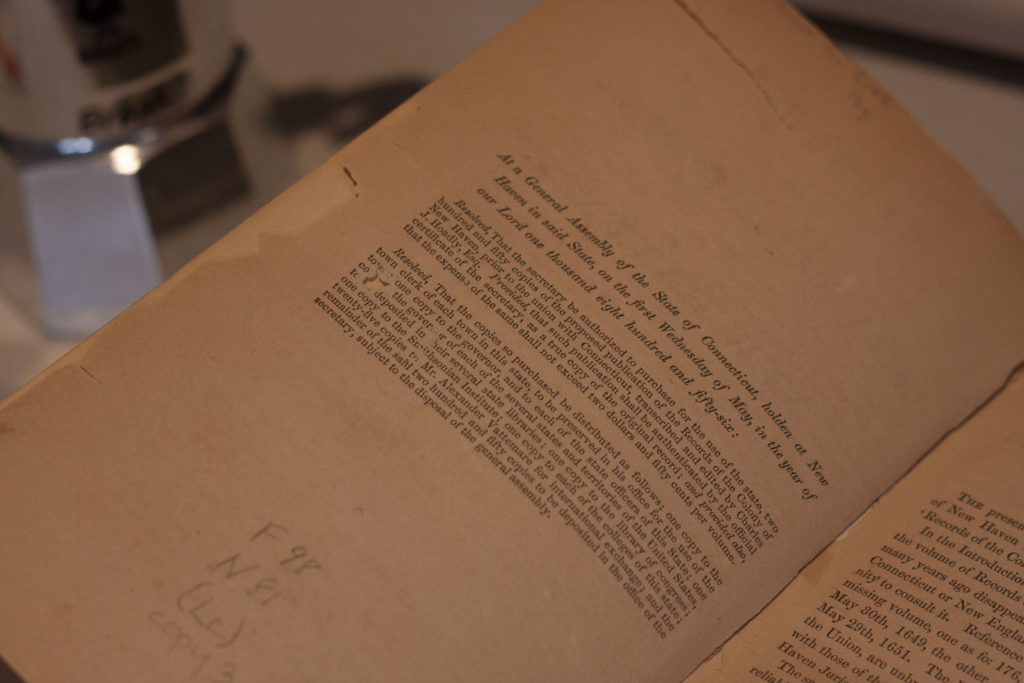

Even though the New Haven Colony recognized no law but the Bible (centuries of English common law notwithstanding) they were not oblivious to the value of precedent. Preserving important records and transactions was a way of putting down anchor in a new society, of asserting identity and manufacturing stability and legitimacy. The trial records Blue prepares for a modern audience were originally written down longhand and archived until 1856, when by legislative order they were transcribed by the Connecticut state librarian and gathered in a small print run for town and government use. Four cases were omitted as “unfit for publication” due to sexual content (Blue restores these from the original accounts).

It’s amazing and fortunate that colonial records have been so carefully preserved in every era. The first entry in the Connecticut State Library’s timeline of important archival dates and events reads:

1741: The Colonial Assembly directs the Secretary of the Colony “to sort, date and file in proper order, all the ancient papers that now lye in disorder and unfiled in his office” before the next sessions beginning in October. The resolution provides five pounds “as a reward for his service.”

Or: Somebody please go all Marie Kondo with this shit on my desk because if this remains lyeing in disorder much longer I can’t even.

Municipal record keeping sounds like a snooze even among the dullest of activities, but throw a few centuries into the mix and even a few scraps of human detail become a godsend. You might argue that when scads of information are being produced every second and you save absolutely everything, you possibly devalue or demystify the record, but there are also needles in every haystack. (See the New Yorker on archiving in the Internet era.)

Watch Judge Blue discuss his work, courtesy of the Connecticut State Library.

Additional Reading:

* Jon Blue, The Case of the Piglet’s Paternity: Trials from the New Haven Colony, 1649-1663

Sarah Vowell, The Wordy Shipmates

Arlette Farge, The Allure of the Archives

R. R. Hinman, The Blue Laws of New Haven Colony (1838)