Have a drink with: Mary Todd Lincoln

Bad taste in psychics; good taste in jewelry

Ask her about: Levitating pianos

George Saunders’ novel Lincoln in the Bardo looks at the metaphysics of the Lincoln family, with what on first glance might seem to be wild creative license. Dramatizing the doubt and grief that colored the President’s life, Saunders gathers a swirl of chatty ghosts to comment on Lincoln’s brief foray into the graveyard after the death of his son Willie in 1862.

Linking the Lincolns and the spirit world isn’t a stretch – though it wasn’t the President so much as his wife who was eager to commune with spirits. Mary Todd Lincoln, driven by family tragedy, was interested in spiritualism through much of her life.

Abe Lincoln’s stance on woo-woo isn’t totally clear. Most historians claim he attended seances on a limited basis, in an effort to kindly humor his wife; others believe that he was, like the First Lady, wholly interested in the possibilities of spirit communication. That Lincoln was an uncommonly soulful man – the sort who might, as Saunders suggests, linger in introspective melancholy in a graveyard – is not, however, in dispute. Maynard writes: “I never saw the depth of sorrow that seemed to rest upon that gaunt, but expressive countenance. Yet there was a light in those deep-sunk eyes that showed the man who was before me as perhaps the best Christian the world ever saw, for he bore the world upon his heart.”*

Still, seances and Ouija were common events in the Lincoln White House, which welcomed a colorful cast of characters.

Mrs. Lincoln was particularly fond of Nettie Maynard and the Laurie family – women rumored to have the ability to levitate pianos – and she so often talked about psychics, clairvoyants and spiritualists that, when Maynard first met Mr. Lincoln, the introduction was hardly necessary:

“He stood before me, tall and kindly, with a smile on his face. Dropping his hand upon my head, he said, in a humorous tone, ” So this is our ‘little Nettie’ is it, that we have heard so much about?”*

Depsite her nervousness at meeting the President, Nettie claims that she went into a trance and spoke with Lincoln for an hour on sophisticated matters (normally well beyond her ken) related to the upcoming Emancipation Proclamation – advising Lincoln to stand firm for the sake of his life’s legacy, and not delay its enforcement.

Charles Colchester, a medium who passed himself off as the illegitimate son of a duke, was another noted visitor. The Lincolns perhaps should have listened to his warnings about threats to the President’s life; but less because of spiritual connections than because Colchester liked to go out and get plastered with his pal John Wilkes Booth.

When Noah Brooks, a Lincoln family friend, debunked one of Colchester’s seances (grabbing the medium’s hand in the dark as he rang bells and thumped drums, and getting a smack on the forehead for his trouble). Mrs. Lincoln explained to Brooks that Colchester had since come to her demanding a free rail pass to skip town, or else he might have some nasty spirit-world gossip about her to disclose publicly.

They agreed to invite the medium to the White House, and when Colchester showed up, Brooks lifted his hair to show off his bloody forehead, snarling: “Do you recognize this?” Colchester grumbled a response about an insult to his honor, and Brooks showed him the door: “You know that I know you are a swindler and a humbug. Get out of this house and out of this city at once. If you are in Washington to-morrow afternoon at this time, you will be in the old Capitol prison.”

Mrs. Lincoln also visited the famous spirit photographer William Mumler, who purported to take portraits of his guests with the hovering spirits of friends and loved ones. She had an image made of her and her deceased husband in 1867, with the spiritualist press claiming that the President’s image had appeared despite Mrs. Lincoln checking in to the studio with her identity in disguise. Mumler went on trial for fraud, in 1869, and was acquitted despite the expert testimony of none less than P.T. Barnum against the practice of spirit photography as a load of hooey.

In the end it is understandable that Mrs. Lincoln was interested in the hereafter: anyone who had buried three sons and a husband might reasonably cling to hope of once again feeling them near, however briefly. In a letter reproduced in the April 15, 1946 issue of Lincoln Lore, she explained herself thus: “I am not either a Spiritualist, but I sincerely believe our loved ones, who have only ‘gone before’ are permitted to watch over those who were dearer to them than life.”

Fun Facts:

The link between First Ladies and spiritualism is generally one born of tragedy: see also Franklin Pierce’s wife Jane, inconsolable and haunted after the death of their son in a train accident. She held seances and consulted with the famous Fox sisters in an effort to find peace.

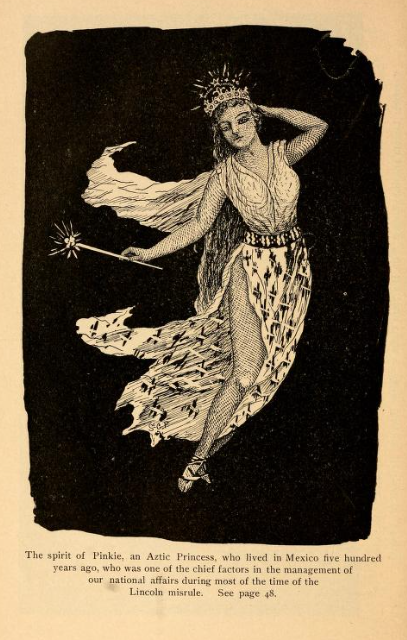

Was Lincoln a spiritualist? Lincoln’s detractors did like to suggest that he was, in part to deflate the dignity of the great statesman. A cartoon in The Copperhead, a conspiracy-minded anti-Lincoln text, depicts a fairylike spirit named “Pinkie” and calls her “one of the chief factors in the management of our national affairs during most of the time of the Lincoln misrule.” By the way, despite his modern political sainthood, Lincoln was surprisingly unpopular in his own time. Anger ran high among the anti-slavery crowd, families angry that their sons were dying at war, and Copperheads (or “Peace Democrats,” a proto-Freedom Caucus of conservative Constitutionalist northerners who opposed Lincoln).

Spiritualists were very vocal in the mid-1800s, many of them very eager to speak on politics or communicate personal and political danger to the President. From the Library of Congress’ Lincoln papers, a letter to the President warns of a poisoning plot in December 1860. The author relays the words of a young girl, “a Clairvoyant (not a Spiritualist),” warning that “a conspiracy exists to murder your Excellency – that it was resolved to employ poison to effect your death, and if no other opportunity presented itself, to bribe your domestics, to consumate the deed.” [sic]

Robert Lincoln checked his mother into an asylum in 1875 against her wishes, concerned not simply for the stability of her mental health but for the fact that she was apparently spending extravagantly on the services of spiritualists. Robert testified against her at the hearing, and let’s be honest: he was definitely someone who wanted privacy and distance from his famous family’s legacy, ultimately setting at a rural estate in Vermont. He also had some loopy luck, having an odd propensity for being near presidential assassinations – he was Secretary of War to James Garfield, who was shot before a train trip the two were to take; and was at the Pan-American Exposition with McKinley when he was assassinated.

Additional Reading:

George Saunders, Lincoln in the Bardo (see also Saunders’ fine Commonweal interview)

* Nettie Maynard, Was Abraham Lincoln a Spiritualist? (1891)

Terry Alford, The Spiritualist Who Warned Lincoln Was Also Booth’s Drinking Buddy, Smithsonian, March 2015

Jeffrey Bloomer, Was Mary Todd Lincoln Really ‘Insane?,’ Slate, November 9, 2012