Have a drink with: The West Point Cadets of 1826

Cold cuts, eggnog, muskets.

Ask them about: really aggressive wassailing

“1408. No cadet shall drink, nor shall bring, or cause to be brought, into either barracks or camp, nor shall have in his rooms or otherwise in his possession, wine, porter, or any other spiritous or intoxicating liquor; nor shall go to any inn, public house, or place where any of those liquors are sold, without permission from the Superintendent, on pain of being dismissed the service of the United States.”

Article 78, General Regulations for the Army, 1825

No one was really looking forward to Christmas at West Point in 1826. While in past years there had been a blind eye towards a nip on Christmas or July Fourth, in 1826 everyone was painfully aware that superintendent Lt. Colonel Sylvanus Thayer intended to put a solid end to any holiday drinking, and had forbidden not only alcohol in the cadet corps but tobacco and cards as well. Staff were on sharp lookout for any smuggled wine or whiskey.

Just a couple days before Christmas, the cadets decided to celebrate the holiday in a warmer, more festive manner than Thayer had in mind: with an eggnog party in the wee hours of Christmas Day. Three cadets collected contributions from their dormitory mates and, with civilian overcoats over their uniforms, they quietly headed to Martin’s Tavern, across the river near present-day Peekskill. Bribing the cadet at the dock for use of a skiff, they returned with two gallons of alcohol and the firm resolution that “there’ll be a good Christmas at West Point this year.” Nor were they the only cadets to visit local taverns for supplies.

Scurrying down the hall to gather in dormitory Room 28, the cadets assembled, and with a fire burning in the hearth and candles lit, they pulled a feast from coats and closets: a loaf of fresh bread here, cold sliced turkey there, some bits of mutton and pork, butter, and for the party’s main event, a pail of milk and handfuls of spices to mix with jugs of Pennsylvania whiskey for eggnog. As the night went on, the room got more crowded and the drink punchier: “the punch grew stronger,” writes Agnew, “as the young men poured directly from the jug into the bucket or carelessly splashed the warm whiskey into their cups.”

Downstairs in Room 5, Jefferson Davis (yes, that Jefferson Davis) was having a 2 a.m. whiskey sing-a-long with his roommates, and avoided catastrophe only because the officer on duty was willing, in exchange for a stiff drink and a promise to keep quiet, to let them have their fun.

Upstairs, Captain Ethan Allen Hitchcock was alerted to the noise in Number 28 and opened the door, behind which the cadets had managed to hide the evidence, somewhat: “the room reeked of wood smoke, burned pork, fowl, and what Hitchcock guessed to be liquor.” Hitchcock turned out some men hiding under bedrolls, manhandled one cadet who refused to remove his cap to be identified, and returned to his post, satisfied he’d shut down the party. The evening was, however, far from over.

Back in Number 5, the party had grown larger and rowdier than its upstairs neighbor, and an itinerant Jeff Davis decided to warn his friends. He burst into the room yelling, “Put away the grog, boys, Captain Hitchcock’s coming!” Hitch was, of course, already there. (Awkward.)

The remainder of the evening was a blurry mess of sauced-up soldiers angry at their superior officers and ready to exact revenge on Hitchcock as the long arm of a very unpopular law:

“In the candlelight, cadets in various stages of drunkenness ran from room to room, waving edged swords and muskets. Yells and curses echoed down the corridors. From time to time a piece of firewood sailed against a door or wall or through a window. An occasional shot was fired. At the south end of the third floor a cadet jerked the window open and inhaled the cold night air, and then suddenly vomited uncontrollably. He tried to push himself back from the window, lost his balance, and crashed to the floor. He crawled to the wall and lay unconscious, passed out in his own filth. This scene was repeated about North Barracks from time to time.”

By the time dawn broke and reveille sounded, formations were a sorry sight. The sober majority of the corps, very confused by the previous night’s noise, were joined by a rash of still-drunk classmates, who were eventually scared into compliance by the arrival of the Commandant of Cadets.

A court of inquiry heard from 167 witnesses over two weeks on the events of Christmas 1826. Rather than run the risk of delegitimizing the young military academy by tossing out a third or more of its cadets (many of whom might be likely to complain to Congress or their influential families), and certainly unwilling to let the incident slide, Sylvanus Thayer court-martialed and expelled nineteen cadets as instigators of the event.

Happy holidays. Pass the nog.

Fun Facts:

Jeff Davis escaped court-martial, having passed out upstairs after being dismissed from Room 5. He did, though, have a colorful history of booze-related incidents at West Point: Thayer had, only a year before the holiday riot, court-martialed Davis for for shenanigans at Benny Haven’s tavern. This is small potatoes, though, compared to the time Davis got blitzed, fell off a small cliff and spend the next few weeks in the infirmary.

Nor was he the only one. Edgar Allan Poe, in his brief time at West Point, reportedly spent more time at Benny Haven’s tavern than on duty.

Why risk a party in the first place? According to James Agnew in The Eggnog Riot, a cadet could reasonably expect to go four years with only a month’s leave halfway through to see family or friends. Combine that with the relative isolation of West Point, a grueling schedule and low pay, and no wonder the cadets were willing to “‘run it’ during the evening hours to visit the hotels and taverns on the fringes of West Point.”

Historical cocktail recipes were not for the weak-hearted. This holiday punch recipe, from an 1869 bartending guide, includes a quart of brandy, a pint bottle of Champagne, some sugar, soda water and a couple token slices of pineapple. The recipe claims that “Six Yale students will get away with the above very cleverly.”

America’s Presidents have put their distinctive stamp on eggnog recipes. George Washington’s recipe includes brandy, whiskey, rum AND sherry; while Dwight Eisenhower’s (remember what a whiz he was in the kitchen?) recommends a full quart of bourbon.

Additional Reading:

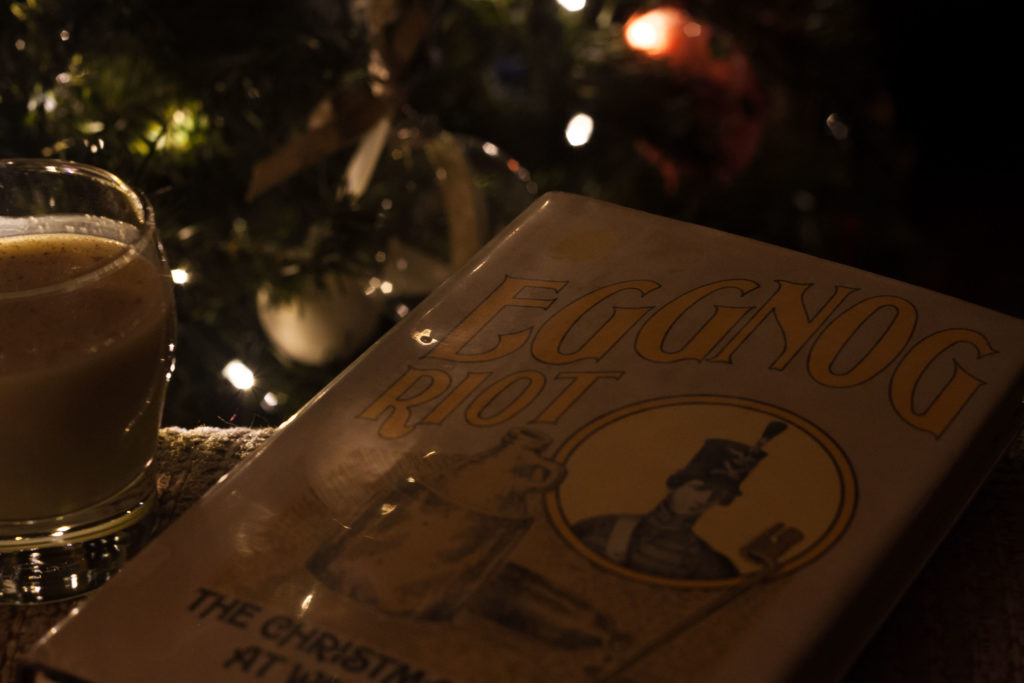

James B. Agnew, Eggnog Riot: The Christmas Mutiny at West Point (1979)

Steven Grasse, Colonial Spirits: A Toast to Our Drunken History (2016)

More detail on the Eggnog Riot at Lapham’s Quarterly and from the U.S. Army.