Have a drink with: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Elementary, my dear Watson.

In the early 1920s, folks in America were generally worn out, in a not unfamiliar way. The geopolitical situation was fraught in the wake of World War I, racial tension was high after the 1919 “Red Summer” race riots, extreme weather events popped up to keep people generally bewildered and awash in adrenaline, and oh, by the way, giant influenza pandemic.

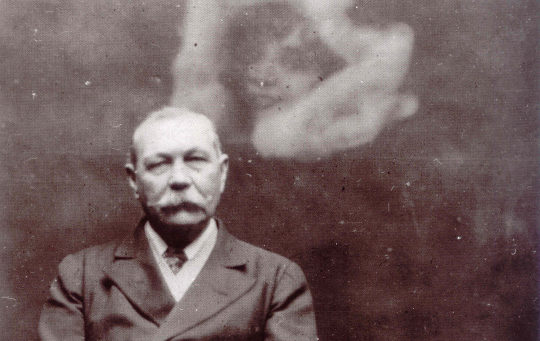

Which goes a fair way to explain why spiritualism – the school of thought that believes we humans can connect with the spirits of the deceased in the great beyond through means like mediums, spirit writing, channeling and photography – experienced a resurgence of popularity in the early 20th century. And there were few spiritualist advocates more ardent – or more famous – than Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who toured America in 1922 waving a Go-Team-Go flag for the spiritualist cause.

I’m in this month’s issue of the Yale Alumni Magazine talking about Sir Arthur’s trip to New Haven, Connecticut. Click over to read the whole story.

Fun Facts:

Poor credulous Doyle was also a believer in the Cottingley Fairies photos, which were staged images in which young girls appeared to frolic and gambol with adorable tiny sprites.

As far as ectoplasm goes, most historical mentions of the term use it in the context of cellular biology. The term appears first in the spiritualist sense in newspapers in 1919 in a discussion of Conan Doyle’s “Vital Message” pamphlet, and he seems to have popularized it in 1922 on the American tour, after which there is an explosion of coverage, including French scientists trying to substantiate his claims, tests on a medium named Eva C., and not a small number of mocking humor pieces.

Doyle mentions the idea that some cut-rate mediums claimed to be relaying the words of departed geniuses like Shakespeare. The idea that people would try to channel notables would have been familiar to a 1922 audience – in 1917, a Missouri writer named Emily Grant Hutchings claimed to have used her ouija board to channel Mark Twain from the afterlife, and take spiritual dictation of his new novel, called Jap Herron. The New York Times book review sourly stated that “[i]f this is the best that ‘Mark Twain’ can do by reaching across the barrier, the army of admirers that his works have won for him will all hope that he will hereafter respect that boundary.”

Additional Reading:

Betsy Golden Kellem, “The Man Who Believed Too Much,” Yale Alumni Magazine, Jan/Feb 2022

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The History of Spiritualism (1926)

David Jaher, The Witch of Lime Street (2015)